Decoy Pricing

Decoy pricing is a pricing method that is meant to “force” customer choice. When customers make a purchase they must often choose between products with different prices and attributes. And when a company decides to maximize the sales of one particular product, it often opts for what is known as a decoy pricing structure in order to influence the consumer in his purchasing decision. In this case, the “decoy” consists of either a slightly lower product price but with a much lower quality product, or on the contrary, a much higher price with a slightly higher quality product.

The decoy pricing strategy relies on two specific effects: the attraction effect and the compromise effect.

Compromise Effect

According to Simonson and Tversky, the compromise effect states that consumers give preference to “median” products, or in other words, it relies on the assumption of “extremeness aversion”. For example, given the choice between three different products, consumers are not likely to opt for the cheapest one because they assume that it is inferior in quality to the other two. They will not choose the most expensive product either as they assume that this product has unnecessary non-essential features. They will therefore choose the median product because this type of product is likely to have an acceptable level of quality and will only contain the necessary features for the consumer. As a result, in this case, a pertinent pricing strategy would involve introducing a top-notch product with a very high price (and big profit margins) in order to create a median effect on other already expensive products, or to introduce a very cheap low-quality product, making the other products appear more attractive.

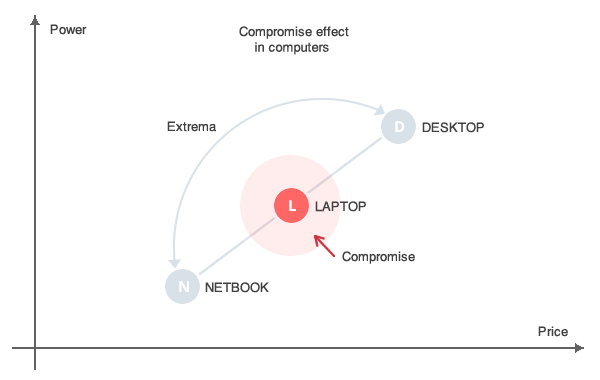

Inspired by Simonson’s work, the following example relates to the computer market and the market for coffeemakers. Both examples are fictional and simplified.

Above is a graphic representation of the compromise effect. Within the computer market, netbooks tend to be the cheapest product, but their power is very limited. The most expensive products are desktop computers, but they are not very portable and are often unnecessarily too powerful for the average user. In this case, laptops would be a good compromise; they are transportable and sufficiently powerful without being as expensive as desktop machines. It is therefore hardly surprising that laptops are favored by the average consumer.

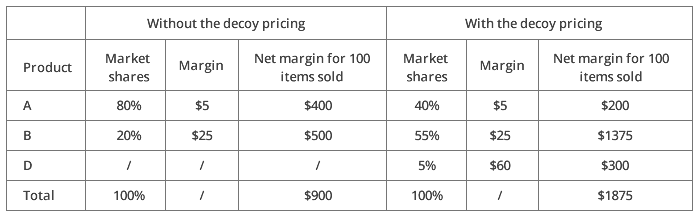

Let’s look at another example, taking into account the decoy pricing method this time. A firm sells two types of coffeemakers: A and B. The price of coffeemaker A is $20 including a $5 margin. The price of coffeemaker B is $50 including a $25 margin. A third coffeemaker (let’s call it D for decoy) is launched on the market by the company and a decoy pricing method is applied to this product. The price of coffeemaker D is $100 including a $60 margin. The firm is aware of the fact that they will sell barely any D coffeemakers due to this product’s high price. Nonetheless, the company’s decision to introduce coffeemaker D on the market is justified as this high-end product will boost the sales of coffeemaker B by creating a compromise effect between A and D.

Using the table above, if we look at the net margin for 100 items sold, we can see that the profit is equal to $1875 with the decoy pricing method. On the other hand, when decoy pricing is not used, the profit stands at only $900. This demonstrates that significantly more profit can be made by using the decoy pricing strategy, even if the real sales of the “decoy” product are very low.

To illustrate this point further, let’s take the example of the technology company Apple that uses the compromise effect in two different ways. The firm’s Apple Watch was introduced as a very high-priced watch (sold at more than $10.000) in order to maximize the sales of the standard Apple Watch that is perceived as a compromise between the high-priced watch and the “cheapest” sports edition. Regarding its iPhone, Apple uses the decoy pricing method slightly differently by offering consumers a cheaper product with more limited features (the 8Gb iPhone) in order to maximize sales on the more sophisticated and function-packed 16Gb or 32Gb versions of the same phone.

Utility and Decoy Pricing

According to rational choice theory, the decoy effect should not really exist in practice. But this theory relies on the assumption that consumers’ purchasing decisions are perfectly “rational” and take into account all the “right information”. However, in many cases (including the examples described above), the consumer does not possess the “perfect” level of information about a product’s utility. As a result, consumers’ purchasing decisions are often made without taking into account full information about any given item. This incites companies to wisely choose their marketing and pricing strategies, ensuring that imperfect information is sometimes deliberately provided to consumers in order to maximize both sales and margins.

In fact, consumers are often not too capable of comparing products that are very different from each other and that have very distinct usage. On the contrary, they are usually able to compare products that are close to each other and therefore know quite well the differences that may exist in the utilities of closely-aligned items. In other words, consumers prefer to make a rational choice vis-à-vis a limited scope of products rather than to get lost in a very wide product scope. In mathematical terms, consumers prefer to reach a local maximum instead of trying to find a global maximum.

Attraction Effect

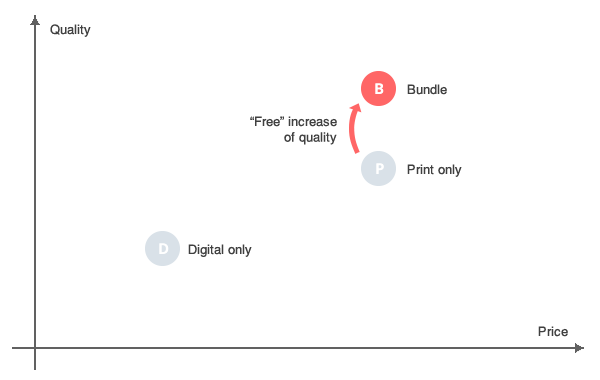

To illustrate the attraction effect, let’s take the example of The Economist, a famous newspaper that implemented a decoy pricing method for its printed and numeric editions. The printed edition costs $ 150 a year, the digital edition costs $50 while the bundle (also see bundle pricing) containing both the printed and the digital editions also costs $150 just like the printed edition alone. The printed edition sold on its own (without the digital version) can be viewed as a decoy pricing method aimed at encouraging customers to buy the whole bundle. In case the bundle option was not available, we can assume that 80% of customers would purchase only the digital version, and the remaining 20% would opt for the paper version. However, following the introduction of the bundle option, 50% of customers now chose to go for the bundle, 50% went for the digital version only, meaning that 0% of customers opted for the printed edition. The 0% is not a pricing anomaly in this case. Rather, this decoy pricing method aims at maximizing the sales of the bundle. The digital edition is perceived to be “free” when included in the bundle and customers like free things.

The Economist example clearly demonstrates the “attraction effect”; an effect that can be considered as one of the main phenomena associated with decoy pricing (as outlined by Simonson). It is indeed difficult to compare two products with extremely different attributes, while it is considerably easier to compare two products with very similar characteristics. Let’s assume that a retailer’s objective is to maximize the sales of one of its products and let’s call this item - product A. Using decoy pricing tactics, the retailer launches another product (product B) whose quality is slightly worse than that of product A, although the two products are very close in terms of their utility. In this instance, consumers can easily make a comparison between the two products offered by the retailer (since the two products are similar in their characteristics) and will therefore choose product A instead of the other newly-launched product B. In this example, the choice is rather simple for consumers to make as the two products are comparable and the decrease in quality of the newer good is easy to detect. As a result, the consumer goes for product A instead of B in order to avoid purchasing a lower-quality product.

Above is a graphic representation of the decoy pricing method employed by The Economist. Consumers have a hard time comparing the difference between the numeric-only and the printed-only versions of the newspaper. But they can easily compare the printed-only version with the bundle. In this case of imperfect product information, customers will choose the bundle because it is the only product which provides complete information about the product in question, and consumers are certain to have all of the features of the newspaper thanks to having both the paper and the digital versions.

References

- Dhar R. & Simonson I., “The effect of forced choice on choice”, Journal of marketing research, 2003

- Simonson I., “Choice based on reasons: the case of attraction and compromise effects”, Journal of consumer research, 1989

- Simonson I. & Tversky A., “Choice in context: tradeoff contrast and extremeness aversion”, Journal of marketing research, 1992