00:21 Introduction

00:55 Observational definition

02:45 The short definition

04:48 Why and How

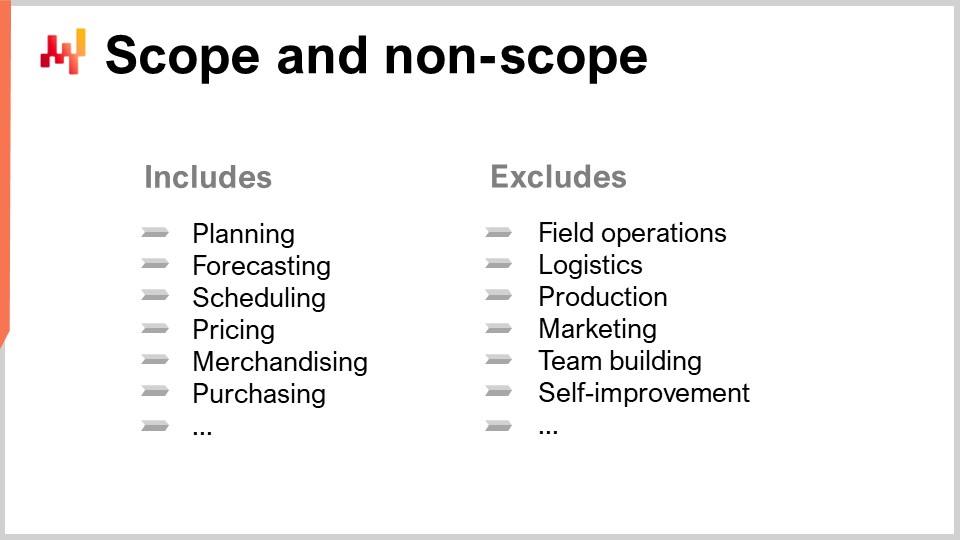

07:58 Scope and non-scope

11:07 Skin in the game + conflict of interest

14:53 Mainstream supply chain theory

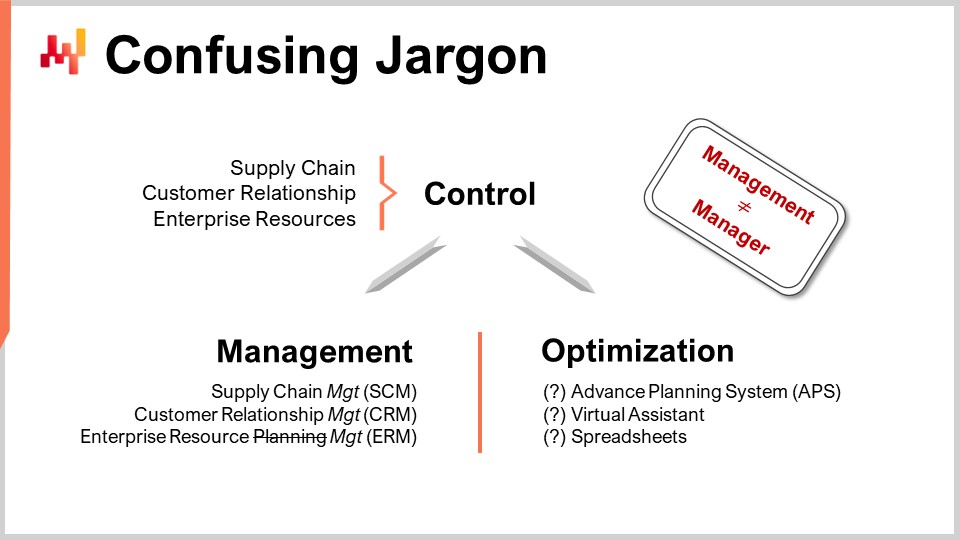

21:53 Confusing jargon

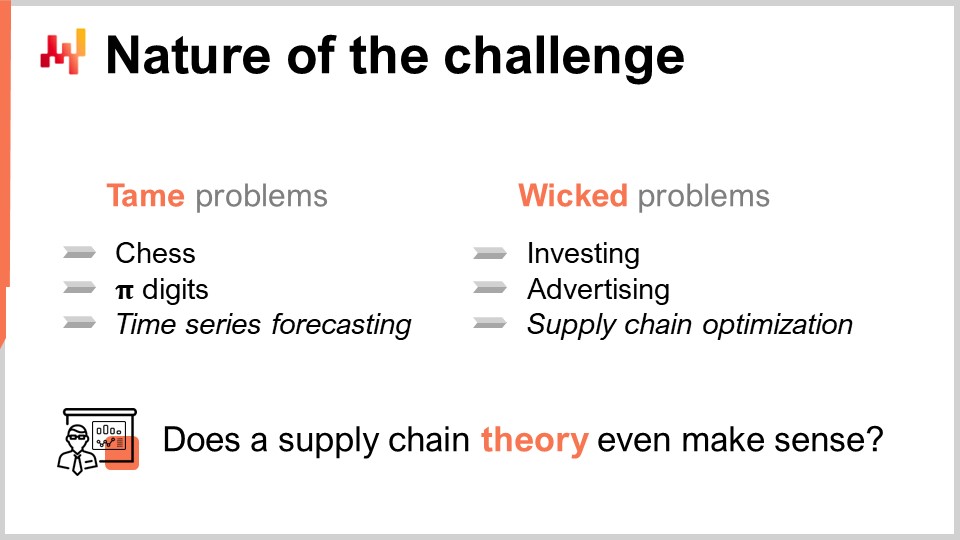

25:42 Nature of the challenge

37:57 The method behind the madness

49:54 In conclusion: two IYI pitfalls

54:02 Upcoming lecture and audience questions

Description

Supply chain is the quantitative yet street-smart mastery of optionality when facing variability and constraints related to the flow of physical goods. It encompasses sourcing, purchasing, production, transport, distribution, promotion, … - but with a focus on nurturing and picking options, as opposed to the direct management of the underlying operations. We will see how the “quantitative” supply chain perspective, presented in this series, profoundly diverges from what is considered the mainstream supply chain theory.

Full transcript

Hi everybody, welcome to the supply chain lectures. I am Joannes Vermorel, and today I will be presenting the “Foundations of Supply Chain.” For those of you who are watching the lecture live, you can ask questions via the chat at any point in time. I will not be reading the chat during the lecture; however, at the very end of the lecture, I will go back to the chat, read the questions, and try to answer them to the best I can. Let’s proceed then.

Let’s start with an observational definition. Forty years ago, my two parents were starting their respective careers at Procter and Gamble. There was a saying at the time that smart people go to marketing, dynamic people go to sales, reliable people go to production, and people lacking all those qualities were ending up in supply chain, or rather, at the time, they were saying they were ending up in logistics. I’ve just modernized the quote, and we really want to do better, which will be the point of these lectures.

I believe there is a grain of truth in this quote, and the interesting thing is that supply chain did not manage during the 20th century to attract as many brilliant minds as it could have. If we look at the 21st century, you could say that supply chain is still niche, and that’s the reason why we can’t attract as many brilliant people as other domains. However, if I look at other niche areas, let’s say online advertising for example, a fairly niche thing, those people tend to attract more than their fair share of brilliant minds, and they have already succeeded in doing so in the 21st century. So now the question is, I believe we need a better, superior form of supply chain to attract those people and to unlock a superior form of profits.

Let’s start with an actual definition of supply chain. I would say that supply chain is the mastery of optionality in the presence of variability when managing the flow of physical goods. By optionality, I mean all the things that you can do or not do on a daily basis. For example, every single time you have a SKU, you can decide to bring more material to this SKU, move the inventory from one location to another, move your price up and down, decide on the assortment in the store, or reshuffle what you have on the shelves in the store, etc. So, you have a very large number of options available to you, and I believe that’s the essence of supply chain – mastering all those options and nurturing them.

Then you have variability, with tons of things that are way beyond your control. You do not control market demand; you can, to some extent, forecast it, but you have no definitive control over many forces that matter. Demand is one of them, lead times are another – you have some control over lead times, but it’s not absolute. The same thing applies to prices: you can control your own prices, but you don’t control the prices of your competitors. There are many things that vary, which means supply chain is not just about orchestration, looking at things laid down in a very clean and precise manner.

And then, obviously, it’s a flow of physical goods, so we have all the physical constraints that apply. We can’t just 3D print and teleport goods, not yet actually, so we need to accommodate all those resource constraints. Supply chain is the mastery of all of that for the greater good of the companies being served and their clients, obviously.

Now, what do we want from these lectures? My goal is to achieve a better, superior form of supply chain that delivers superior performance. I am a big believer in quantitative methods and a financial perspective, but that’s just a belief; there’s nothing scientific about it. I will try to uncover a certain methodology to achieve that and clarify the goals, as there are a lot of nuances and subtleties regarding what “better” means precisely. We will cover those things throughout the lectures.

These lectures are intended for a fairly large set of audiences, and by the way, some of these audiences may be in conflict. One of my goals for this series of lectures will be to put some of the audiences out of their comfort zone. On one side, we have supply chain executives, who face the challenge of leveraging modern computing hardware and software for their companies and clients. There is a need for technical depth in these matters; otherwise, it’s hard to guide, manage, coach, and mentor people if you don’t really comprehend what they’re doing.

On the other side of the spectrum, we have IT specialists and data scientists who might be eager to see the code or the formulas. To them, I would say: hold on, you have powerful tools at your disposal, but do you know how to wield them business-wise? Are you confident that what you’re doing is really in the interest of your company or the companies that happen to be paying you if you’re a contractor? My humble experience is that there are many ways to be misguided when approaching supply chain. The ambition of these lectures is to provide some depth in terms of business vision and street-smart intelligence so that you can do better for the supply chain.

Let’s clarify the scope and non-scope for supply chain. In terms of scope, I will be including very classical things like planning, forecasting, and scheduling, which are the usual definitions of supply chain. However, I will also be including, from my own perspective of supply chain, pricing, assortment, and merchandising. All of these things are part of the supply chain from my perspective. If you look at supply chain as all the options you have to serve the market, pricing is obviously one of them. It doesn’t really make sense to forecast demand if you don’t know what your future prices will be because if you can lower the price, you will inflate the demand. It’s just very mechanical. You cannot treat demand forecasting as if it was independent of your pricing strategy; they are obviously completely entangled. The same applies to merchandising. The demand you will see in a store depends on what you put on the shelves. It’s relatively obvious that if you keep your goods in the warehouse and don’t put them in front of customers, you sell less. The idea that you can keep these two things apart, I believe, is partly insane. So, all of that, and obviously, purchasing matters. All those options through the company, for me, are part of the supply chain.

However, what is not part of the supply chain, from my perspective and the perspective adopted through these lectures, are things like logistics. I’m not denying that managing truck drivers is exceedingly difficult and essential for many supply chains to operate. You need to accommodate people working in the field, and those jobs are tough. You need to keep morale up, lead those people, and make sure they don’t suffer from hazards or accidents. It’s quite difficult in practice, especially when people are tired, dealing with machinery, and dealing with heavy equipment. But I will be excluding those concerns from these lectures. They are important concerns, but not the focus here. I’m focusing on the optionality, the mastery of opportunity, and the mundane decisions you can make every day to improve the service to the client from many directions. I will not be discussing team building, self-improvement, and related topics, as my perspective is more quantitative on these matters.

Now, a small disclaimer: I do have more than my fair share of conflicts of interest. I am the CEO of a software company that happens to be selling supply chain software intended for the predictive optimization of supply chains. So, obviously, I am not exactly neutral in this game. Nevertheless, I believe that my perspective has some value, especially considering the way Lokad is approaching supply chains.

Lokad was created in 2008, and at the time, I started as a forecasting-as-a-service provider, but rapidly, like four years later, it evolved into a predictive supply chain optimization-as-a-service company. Our experience is, I believe, relatively unique, as we are now literally operating about 100 supply chains on behalf of our clients. When I say “operating the supply chains,” I don’t mean that we provide the software and our clients call all the shots and do everything through menus and buttons. Lokad delivers a service where we typically provide optimized end-game decisions. When I say end-game decisions, it’s literally decisions like: what should be the price today for this article? How many units should you move from this distribution center to this store? How many units should you manufacture today in this plant? How many units should you order from one of your overseas suppliers today? Lokad goes directly to these end-game decisions. Of course, our clients don’t write blank checks to Lokad, so it’s a suggestion that we are making. Our clients still have the opportunity to veto what we suggest. Nonetheless, my casual observation is that for a large majority of our clients, we have about a 99% hit rate where we suggest things and they are rolled out in production just as such, with no manual override. It’s literally just a stamp of approval, and that’s it. We even have quite a few clients where the decisions are automated and flow directly to the ERP.

I believe this experience gives us a unique perspective on what it actually means to optimize a supply chain in the real world. It’s not an experience like a software vendor that sells licenses and says, “Thank you very much, you’re now the proud owner of one of the licenses of my products, where you’re just printing your own money through your software licenses.” We are directly in a position of having skin in the game. We have to do well. The vast majority of Lokad’s clients go for a monthly subscription where they can quit on us at any time, with no implementation fee. This gives us a certain survival instinct of how to actually succeed in supply chain by delivering actual value, knowing that our clients can quit on us at any point.

This brings me to how we achieved this and a look at what is typically referred to as the mainstream supply chain theory, as opposed to the quantitative supply chain perspective of Lokad. Two books, “Inventory Management and Production Planning” by Silver, Pyke, and Peterson, and “The Fundamentals of Supply Chain Theory” by Schneider and Shen, I believe, represent the gold standard of the mainstream supply chain theory. These books are extensive compilations of the last 60 years of supply chain research, which goes by various names like operations research, forecasting, business optimization, and so on.

These books, in terms of academic works, are very well-written, clear, and to the point. Each one is about 800 pages long, quoting about a thousand papers, with a massive bibliography at the end. They include exercises and plenty of other elements. These books are very coherent, well-written, and I believe what they present is fundamentally correct from a mathematical point of view. Furthermore, these two books are also an accurate depiction of research that took place over the last four to six decades in these fields, which is why I qualify them as the mainstream supply chain theory.

However, are these books truly satisfying? I would say disappointingly not. When I founded Lokad, I already had the first of these two books in my hands, and I had been trying to apply this mainstream supply chain theory with my clients for four years. Over the decade-plus of experience that I have had at Lokad, I’ve had the chance to discuss with literally close to two or three hundred supply chain directors, and I’ve never seen any company where it was working, not a single one.

Sometimes the situation can be a bit confusing because some terms from the mainstream supply chain theory, such as safety stocks, are used by companies. Yes, companies are using safety stocks, but when you have a close look at the way safety stocks are implemented in companies, it usually comes with plenty of twists and numerical oddities that have absolutely nothing to do with what the theory is saying we should do. And yet, the many companies that I’ve met were absolutely correct to bring those twists.

In large companies, there are already people who are aware of this theory. I don’t think that the mainstream theory didn’t succeed because there’s too much ignorance going around. I’ve met many supply chain directors who are familiar with this theory. Obviously, they don’t know the hundreds of formulas by heart, but they know they exist. Even if the supply chain director doesn’t happen to know those formulas precisely, they have someone on their team who does or a consultant who knows them. This knowledge is truly mainstream and has been taught at universities for decades.

Ignorance is not the explanation. Interestingly, the mainstream theory is very present in the mainstream ERP implementations, which propose textbook implementations of the supply chain theory. What is intriguing is that I’ve seen over and over again that the mainstream supply chain theory, when cleanly and properly implemented into an ERP, just doesn’t work. People fall back on Excel spreadsheets and feel bad about it. They feel as if there is some scientific truth, but they’re not quite there yet, so they have to do some dirty data crunching on spreadsheets. They hope that at some point in the future, they will manage to use the features provided by the ERP.

However, this story has been unfolding for three decades now, and my counter-proposition to you is that it’s just not working. It’s literally not working. What people are doing with their spreadsheets contains an essence of truth, and that’s where we should be looking. The problem I have with the mainstream supply chain theory is that it’s literally not working. At a philosophical level, I have one more issue: these books are written in such a way that they cannot be contradicted by the real world. For those of you who have read a bit of epistemology, you might recognize Karl Popper’s argument of falsifiability. I will be getting back to that later in the lecture. A scientific theory needs to take risks with regard to reality. You cannot do science if what you say cannot be challenged by the real world. My problem with these two books is that they are immune to the real world. They cannot be challenged because what they’re saying is perfectly true and consistent. It’s like small tidbits of math that have their internal consistency, but they are immune to reality. This is the crux of what I think is deeply wrong with the supply chain theory, or at least one of the aspects.

To make things even more confusing, let’s look at some jargon with regards to supply chain. In this series of lectures, I will distinguish between what I refer to as management versus optimization, both of which fall under the umbrella of control. When I say supply chain control, I mean two very different things: supply chain management and supply chain optimization. When I say management, it has nothing to do with a manager or an executive like a supply chain director. Instead, I’m referring to an accountant’s perspective, where you just manage the records.

Supply chain management boils down to managing the information, processing it, and handling the mundane data entry and workflows. This is similar to customer relationship management (CRM) tools, which don’t do anything with your clients but record their names, hot leads, etc. Some misguided market analysts in the ’90s coined the term ERP (enterprise resource planning). I believe this term was misguided because ERPs have nothing to do with planning. They would be better named enterprise resource management, as they keep track of all the assets owned by a company. Supply chain management refers to keeping track of items, orders, processes, and various permissions.

On the other side, we have supply chain optimization, where the real intelligence lies. In this area, we have things like APS (advanced planning systems), but I’ve added question marks because it’s not entirely satisfying. The problem with forecasting and planning perspectives is that they’re not taking ownership of the endgame financial performance of the supply chain. For those who have watched my Lokad TV episodes, this is what I mean when I criticize the focus on percentages of error instead of dollars of rewards and errors. That’s what I’m talking about. So, we can think of it in terms of tech, like virtual assistants or spreadsheets. While spreadsheets may not be a super smart piece of software, they align with this vision of having management, which is the electronic counterpart of what is happening in the real world, and optimization, which leverages all the optionality of the decisions we have to make. In these series of lectures, I’m definitely adopting the perspective of supply chain optimization. We are not here to figure out how to create the next warehouse management system (WMS); instead, it’s about optimizing our supply chains and making them better.

Now, let’s have a closer look at the supply chain problem. What is the nature of this challenge? We have a subtle but profound distinction to make: is it a tame problem or a wicked problem? Most practitioners and data scientists are not even aware of this duality. A tame problem is something like chess, where you have well-established rules. It can be very complex, but the rules are clear, and the problem is perfectly specified. Once you have such a problem, it’s just a matter of pure engineering to crack it. It can be difficult, as it took decades of effort for computer scientists to develop a computer capable of outperforming world champions. However, there was little doubt that a game like chess would eventually be solved through computational methods.

Time series forecasting in supply chain management is also a well-established problem. But the big question is, does it even reflect what is happening in a real supply chain? My proposition is that it does not. If we go back to those books on mainstream supply chain theory, time series forecasting would feature prominently across many chapters. I’m telling you that it’s not even the right way to look at the problem. We have to consider that supply chain problems are wicked.

What do I mean by wicked? Supply chains are complex and include people, processes, machines, and hardware, among other things. But first and foremost, they involve many people. Interestingly, as soon as you have people involved, the problems become very different. Let’s have a look, for example, at investing. Imagine you want to invest money, perhaps from a large inheritance, and you want to make a wise investment. You can seek financial advice, but it’s difficult. Let’s examine the incentives of the market when you’re seeking financial advice. If you’re giving financial advice, what is your incentive? Your incentive is to encourage people to buy a certain stock because you believe in its value. As people converge to buy the stock you’re promoting, you can discreetly sell your shares, potentially causing others to incur a loss. This mechanism is known as “pump and dump.” It’s difficult to find unbiased financial advice because those with a reputation have a massive incentive to engage in pump and dump schemes.

Let’s consider another example. Imagine you’re running a fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) company, and you want to create a good ad. What is a good ad? There is no clear answer to this question. If you could prove that you have the best ad and your competition agrees, they might create ads very similar to yours. This would cause your message to become undifferentiated from the competition. Wicked problems don’t have good solutions or optimality because even if you think you have something very good, it can be copied. Competitors can respond to your moves and undo any optimization or advantage you thought you had.

The essence of the game being played is dynamic, and your opponents are smart and can respond to what you’re doing. One of my criticisms of mainstream supply chain theory is that it approaches supply chain problems entirely from the tame problem angle. The idea that there can be adversarial behaviors is absent, and I believe that’s unrealistic. If we look at supply chain optimization, we can see adversarial behaviors at every level. To achieve any degree of supply chain optimization, you have to be resilient to these problems.

First, it’s an illusion to think that the interests of employees are always aligned with the interests of the company. While there is often some alignment, the average duration of employment for people under 30 with an engineering degree in France is just 1.5 years. These individuals change companies frequently, so it’s unrealistic to expect infallible loyalty to any one company. They want to do well, but it can’t be assumed that their loyalty is absolute.

Next, consider software vendors, who have their own financial interests in mind. Large ERP vendors, for example, have increased their maintenance fees significantly over the years. The more problems they create in terms of production, the more need there is for maintenance – which isn’t necessarily aligned with the best interests of the company.

As for consultants and IT companies, their best interest is to make the most of any problems they identify. They may extend their services and bill for hundreds of days of work, which isn’t always in the best interest of the client company. In these examples, I’m playing devil’s advocate, but it’s important to recognize that supply chain management is a wicked problem.

Even when taking a purely cooperative perspective, strategies like undercutting competitors by passing bigger orders or shrinking assortments can disrupt the supply chains of competitors. Supply chain management isn’t a game that’s meant to be played nicely. If we look at successful companies like Amazon, they can be rather ruthless. It’s not necessarily a core value to be imitated, but it’s something that can’t be ignored.

Companies may have different values, but they can’t pretend that supply chain problems are tame, with well-specified issues and no adversarial behaviors. Competitors may find ways to cheat or undercut through creative strategies, which can’t be overlooked.

So, does supply chain theory make sense from this perspective? I believe it does. However, it’s important to consider that analogies are weak forms of reasoning. If we were talking about a medical science that only applied to idealized patients, it wouldn’t make sense. When a patient seeks treatment from a doctor, they usually aren’t young and in perfect health. They can be older with many other problems, such as being overweight or having pre-existing conditions. Modern medicine doesn’t only deal with idealized patients who are almost perfect in every regard, minus the pathology of interest; it deals with real patients with a multitude of problems. I believe that supply chain management should be similar – dealing with real companies that have many issues in addition to the problem of interest, and a theory that can cope with reality.

A theory is necessary because it provides the perspective and framework for approaching problems in this field of study and practice. At worst, one can have a bad or unspoken theory, but there is always some form of theory present. The goal is to develop a better form of theory, which is what I will be attempting to do in these lectures.

This is a vast undertaking, with nearly 100 sessions planned. I apologize for the length, but we are tackling complex problems that do not have simplistic solutions. The first step is to expand our horizons. One criticism of mainstream supply chain theory is that it only looks inward, which is fundamentally flawed. Supply chains do not operate in a vacuum; there is a world out there, and we need a deep understanding of various fields to truly improve supply chain management.

There are many areas we can learn from, such as epistemology, medical science, computer science, machine learning, and numerous numerical recipes. Data scientists in the audience may be familiar with the idea that there is more to supply chain management than traditional methods. However, be cautious – recent books on the fundamentals of supply chain theory are well aware of modern machine learning techniques, even including chapters on support vector machines. The problem is not a lack of access to these techniques; it’s not the core issue.

To address these problems, we need a broader view encompassing a wide variety of fields, including economics. We will cover around 15 sessions on diverse subjects, which I believe are essential for gaining a high-level perspective that is approximately valid, rather than being exactly wrong. We have a deep methodological problem related to reproducibility, which is a fundamental aspect of many sciences. In physics, for example, you can set up an experiment, carry it out, and compare the results with theoretical predictions, such as Maxwell’s equations for an electromagnetic field. You can replicate these experiments at will, which is a powerful aspect of hard sciences.

In softer sciences, like medical science, reproducibility becomes more challenging because every patient is unique. However, with the right methodologies, you can still reach consensus and achieve some degree of reproducibility. For instance, well-engineered vaccines demonstrate a positive trade-off for a population, despite occasional accidents.

In supply chain management, achieving reproducibility is very difficult. It’s impossible to experiment with one million supply chains. At Lokad, it took me a decade to work with over 100 companies with some degree of intensity. Realistically, by the end of my career, I might reach 1,000 companies, but a million is entirely unfeasible. Companies are more unique than patients because they consist of many individuals operating in diverse markets, conditions, histories, and strategies.

In addition to the reproducibility issue, there are other methodological problems, such as conflicts of interest. Everyone has conflicts of interest, and it is unrealistic to seek a figure without any. Academia often presents itself as having no conflicts of interest, but having spent time in academia, I have witnessed many conflicts related to the “publish or perish” mentality. Researchers need to select problems and perspectives that align with getting their papers published, which may diverge from what makes a company profitable.

There are many good ideas that cannot be published because they may be too simple or not suitable for broadcasting due to adversarial behavior. Simplicity is beneficial, except in academia, where everything must appear more complicated and scientific. However, good science should not involve accidental complexity; it needs to be as simple as possible, but no simpler. Mechanical sympathy is another aspect that is important in supply chain management. Supply chains do not operate in a vacuum; they operate on a substrate, which happens to be modern computing hardware and enterprise software.

What is surprising is how little even technically-minded people, like data scientists, know about modern computing software and how it works under the hood. If you want to be proficient in quantitative supply chains, you need to have mechanical sympathy, similar to Formula One drivers who are familiar with their engines, even if they are not engineers capable of re-engineering them.

It is important to understand what computing hardware can and cannot do, as well as being knowledgeable about enterprise software. Many supply chain rules are based on a profound misunderstanding of what modern computing hardware can do. It is astonishing to see people with software engineer or data scientist titles who know very little about computer hardware.

Additionally, you must be familiar with enterprise software, as it is the ecosystem in which your solutions will operate. You will interact with ERP systems, e-commerce platforms, WMS, MRP, EDI, and VMI systems. The landscape is complex, and all these systems are constantly changing. You need to understand how to work compatibly within this dynamic environment.

One of the problems with mainstream supply chain theory is that it approaches the problem from the wrong angle. Companies have ERPs that already implement the mainstream supply chain theory, but it does not work, and people resort to using Excel spreadsheets instead. Excel offers what your ERP does not: programmatic expressiveness. This happens to be of high importance, and there is a lot of enthusiasm around Python and data science nowadays. This enthusiasm is not related to deep learning, but rather the simple programmatic expressiveness that you can get with an actual programming language.

As soon as you start programming anything to pilot your supply chain, the question arises: what kind of programming language do you want? Can you have superior paradigms that will give you better productivity, more reliability, better results, and improved financial performance? There are quite a few notable paradigms that you need to be aware of, as they can be game-changers in your efforts to make your supply chain practices more quantitatively driven.

In conclusion, there are two intellectual pitfalls. The term “intellectual yet idiots” is borrowed from Nassim Taleb, and it refers to a class of problems that only happen to educated people. The first problem is naive rationalism, which is rampant in academic circles and among software vendors for different reasons. In academia, naive rationalism is fueled by the need to idealize and simplify situations to publish mathematical theories. This often leads to simplistic models, making the vast majority of academic papers of little use for businesses with real-world problems.

For software vendors, the problem is a cost issue. Simplistic recipes cost less to develop, making it a strong temptation for vendors to minimize costs by sticking to them. This leads to an overemphasis on simplicity and a dismissal of the complexities that make supply chain management difficult and interesting.

The second problem is underwhelming recipes or “TED Talk-ish” solutions, where there is a lot of enthusiasm, grand vision, and people talking big but doing little. Here, we encounter something that is rampant among consulting sectors and gurus, where they provide grand theories that happen to be exceedingly weak when you look at the depth of material and how much you can truly put into practice from what they’re proposing. It makes you feel good, yes, but does it translate into superior supply chain results? I’m not so sure. We need to do things that are street smart, avoiding naive rationalism, and going into real technical depth because it should not be all speech; we need to go to something that can actually run an actual supply chain in the real world, with all the quirks that happen to be accidentally present.

Thank you very much for your time today. Now, I will proceed to the questions.

Question: Setting pricing alongside demand planning is very logical in theory, but in a large company dealing with thousands of SKUs, it’s much more complex. Is it realistic in a huge company, especially with cross-functional teams which may have conflicting interests at each point of time?

That’s a great question, and we will address it in later lectures. In short, I believe that the 21st-century approach of dividing and conquering, where you have completely disaggregated large corporate structures into many divisions, is not rational or scientific; it’s actually quite the opposite. Companies will need to relearn how to have a captain, and sometimes it’s not more scientific to split divisions across many teams. However, we need to have recipes, practices, and tools that can be operated at scale by just a few people, as that asks the question of productivity. We need those programming paradigms, and this will be addressed in later lectures.

Question: From my perspective, pricing, cost, or cost is the most apparent conflict of interest. Cost and price are the domain of finance, whereas volumes and, or teeth are the domain of supply chain.

Yes, I agree, and here we have to reinvent S&OP in ways that are more appropriate to the present state of affairs of supply chain. Supply chain operates on a substrate, which includes modern enterprise software and modern computing hardware. Those things can provide a tremendous substrate to do more, to do things that were just plain impossible with a meeting-driven S&OP process of old.

My own take on supply chain is a financially driven perspective. However, don’t confuse me with being driven by finance. We need to count dollars and euros, and this is true for supply chain as well as for marketing and production. We need to bring all those dollars and euros together, and there should be a method to that.

Question: Pricing optimization should be done together with demand forecasting and setting safety stock targets. The unification is so far ahead that I didn’t start yet to dream about it.

Yes, good comment. It can be done, and the key message is that it’s better to be approximately correct than exactly wrong. It’s okay to be crude if crude is all you have. It’s better than being blind and pretending the problem doesn’t exist in the first place.

Question: How can a midsize organization optimize its warehouse operation using technology and software by choosing the right WMS and ERP?

My message to you is that WMS and ERP have nothing to do with optimization, and the sooner you realize that, the better. If you think that ERP and WMS have anything to do with optimization, then you’re setting the wrong expectations. By their very design, they are in the management side. I know that many vendors are promoting optimization because that’s what sells the software, but it’s very wrong and misguided. We need to have mechanical sympathy. By their very design, those tools are irremediably unsuitable for optimization. It’s okay, though – management is important, and those tools can provide tremendous value for that, but do not set the expectations for optimization.

Question: Is there a big concern in evaluating and selecting the right ERP and WMS vendor for those organizations which are not tech-savvy?

Well, I guess the answer would be that if you want to buy fine art and there is a merchant that tells you this painter is of great renown and obviously this painting is worth millions, do you buy it? If you want to be good at buying the right paintings in terms of fine arts that are really worth your money and are going to be an asset or an investment, you need to be savvy in terms of what you’re buying. Due to the conflict of interest, if you delegate that trust, you’re going to be taken advantage of. My message is that if you want to buy tech, you need to have an educated opinion on that and go deep to look under the hood. Most of the good and bad properties of enterprise software are by design. Once an enterprise vendor has made a certain set of design choices, there are things where, by design, they will be terrible and it cannot be recovered. If you’re good at certain things, you will be very bad at certain other things.

Question: What is the function of QA/QC in supply chain?

A very good question, and I have a fairly opinionated answer to this question. It will come in my third session, which will be product-oriented delivery. QA and QC, as far as supply chain is concerned, is really about the supply chain product that ends up being delivered. I really differentiate the sort of things that I will address and not address in these lectures. I do not address things like whether my truck drivers are drunk or not. That’s an important problem, but I had to choose a certain scope for these lectures, so I’m focusing on the optionality side of the problem, not the people management side of things. Quality control and quality assurance are very big on my agenda, but that will be from a more product-oriented vision of the supply chain, which will make more sense in lecture number three.

Question: How do you succeed with a plug-and-play approach where the customer’s supply chain maturity is weak?

I challenge the idea that there is a plug-and-play approach. Lokad is not plug-and-play; it’s relatively swift to deploy, but it’s not plug-and-play. It takes a few months, and I don’t think it’s even really possible to achieve anything that would qualify as plug-and-play. This will become more evident in the further lectures. Remember, this is a wicked problem that we’re tackling, so there is no plug-and-play approach to solving wicked problems; by design, it’s just not possible. I challenge the assumption that when people tell me their supply chain knowledge is weak, I ask, “according to what?” If you tell me that your supply chain knowledge is weak because you haven’t read the two books I’ve just presented, I would say yes, you’re missing something. But you might not be missing much. If your measurement is just being knowledgeable about mainstream supply chain theory, it may not matter that much. Usually, the question is more about the willingness to change yourself. People, especially with the internet, can learn a lot of things. At Lokad, we go from engineers fresh from engineering school to capable supply chain scientists in six months. I believe you can take people who are fresh, willing, and smart, and in six months, they will be able to do a lot.

Question: You have been talking about the need for countervailing KPIs and end-to-end visibility for some time. Is it not an issue of maturity?

Yes, but only if you have the right perspective. I’ve met many companies that were saying they were exceedingly mature and had hundreds of people involved with their S&OP process and a bazillion of KPIs. They typically have an enormous BI team as well. This is not maturity; it’s an illusion of maturity. You need to have the right perspective on the problem, and it can be fairly simple. Even end-to-end indicators don’t have to be overly complicated.

Question: Besides your own books, what recommendations do you have for the quantitative supply chain?

Just watch the next lectures; I will do my best. I would not recommend those two books if you don’t believe what I’m saying. For an alternative perspective, just give us time to go through the supply chain. By the way, there are already over 100 Lokad TV episodes.

Question: Will IoT tools be discussed in the lectures?

Yes, they will be discussed. I will not focus on specific tools, unless there are really specific questions asked about them. First, we need to address the programming paradigms for these tools and consider the core design that yields the most interest for what we’re about to do. We don’t want to be distracted by an endless series of open-source projects that are all very cool and shiny. We need to understand how to have high-level judgment to make our assessments and even know if they are truly relevant with regard to what we want to achieve.

I believe there are no further questions. If anybody wants to get in touch with us, don’t hesitate to send an email to j.vermorel@lokad.com. By the way, we will have the next lecture at the same day and time next week, and the same goes for the following week. The lectures will be on Wednesdays at 3 p.m. Paris time. I apologize to our Australian and New Zealand friends, as the time is not ideal for you. I know there are a few people from those time zones in the audience, so I wish you a good night and hope to see you next time. Thank you very much.

References

- Inventory Management and Production Planning and Scheduling, Edward A. Silver, David F. Pyke, Rein Peterson

- Fundamentals of supply chain theory, Lawrence V. Snyder, Zuo-Jun Max Shen