00:21 Introduction

00:57 Average - Supply Chain terms shaping the world

03:58 The story so far

05:02 Promitheiadynamics

06:43 Better UX via Tougher Supply Chain

21:26 Programmatic Options in Supply Chain

40:22 Supply Chain (d)evolutions

58:21 Conclusion: XXIst century supply chain is about conquering complexity

01:01:04 Upcoming lecture and audience questions

Description

A few major trends have been dominating the evolution of supply chains over the last decades, largely reshaping the mix of challenges faced by companies. Some problems have largely faded away, such as physical hazards and quality issues. Some problems have risen, such as overall complexity and competition intensity. Notably, software is also reshaping supply chains in profound ways. A quick survey of these trends helps us understand what should be the focus of a supply chain theory.

Full transcript

Hi everyone, welcome to this series of supply chain lectures, and a happy new year. I am Joannes Vermorel, and today I will be presenting “21st-century Trends in Supply Chains.” For those of you who are attending the lecture live, you can ask questions through the YouTube chat at any point in time during the lecture. I will not be looking at the chat during the lecture, but at the end, I will get back to it and do my best to answer all the questions, starting from those at the top of the chat. So let’s proceed.

In order to look far into the future, it is of interest to start by looking far back into the past. It’s interesting to observe that civilizations emerged at the same point in time as supply chains. Indeed, even in high antiquity, the first cities had to have supply chains to sustain themselves. So, the very idea of having cities and having supply chains was something that had to coexist; one could not exist without the other.

Besides those obvious elements, supply chains have literally shaped our worldviews, quite literally in the sense that they have shaped the way we see the world. As an illustrating example, one of my favorites is the term “average,” which is a basic mathematical or statistical concept. The term itself originates from a supply chain practice about five centuries old and comes from the French “avarie” or the Italian “avaria,” which means damage to a ship. However, the underlying idea is much older, closer to 3,000 years old, and was a supply chain practice pioneered by the ancient Greek merchants known as the General Average, a marine insurance mechanism.

The idea is very simple: when you have cargo on a ship that happens to be lost, there is a practice where everyone who has put cargo on the ship in the first place acts as an insurer for this cargo. They will reimburse the damage proportionately to the value of the cargo they put on the ship in the first place. This mechanism is of practical interest because it removes a series of bad incentives when it comes to shipping cargo, such as having favored placements for the cargo on the ship. For example, cargo that is above deck is much more at risk than cargo that is below deck.

My question for you today would be, if we look at something as profound and fundamental as the average, which originated from a supply chain practice, what would be the sort of supply chain practice that will emerge in the 21st century? One that will shape the worldviews of mankind quite literally in ways so deep and profound that it will become, 3,000 years from now, a basic word in the dictionary and a fundamental mathematical concept. I’m not sure I have a definitive answer to this question.

So, the story so far: this is the fifth supply chain lecture of mine. I started with the foundation of supply chains, establishing the nature of the problem we have to address, which is a wicked sort of problem. Then, we went through a series of requirements to achieve greatness for modern supply chains, the essence of this idea of quantitative supply chains. Lastly, the product-oriented delivery, and by product, I mean software product, we reviewed how we can have a capitalistic and accurate supply chain practice. Finally, through programming paradigms, we’ve used a series of ways to achieve a superior supply chain practice at scale by focusing on the right sort of things. Today, we are looking at the 21st-century trends for supply chains.

Promitheiadynamics, a made-up word of mine, refers quite literally to the study of the evolutions of supply chains themselves. My proposition for you would be that in open supply chain systems, the total entropy of the system can never decrease. You could see that as a loose supply chain equivalent of the second law of thermodynamics, except that here the system is open, and the entropy refers to informational entropy instead of thermodynamic entropy. We’ll revisit this in a later lecture as well.

There are three classes of reasons that support this statement. One is that you can deliver better user experience, quite literally adding value for supply chains, but there is no free lunch, so it has to be paid for in extra supply chain sophistication. The second one is that, in the 21st century, a series of options that I refer to as programmatic ones emerge. The only realistic, practical way to exercise any of those options is to use a computer program. Finally, a series of factors are not strictly relevant to supply chain per se, but they play a big role in the increase of entropy complexity of supply chains themselves.

Obviously, you can add value for supply chains. I believe that throughout the 21st century, the focus will be on adding more and more value. If I compare the situation to the 20th century, it was a century where we completely revolutionized the way things were produced. We almost completely automated the production side of the problem, except for a few specific verticals like textiles, which are still very manual but are on the verge of being fully automated.

Interestingly, in the dominant supply chain practice of the 20th century, the idea was to concentrate demand as much as possible into a few hotspots. That’s exactly what the superstore, hypermarket, or mall is about: concentrating all customer demand in one place so that it’s straightforward to have mass production, mass transportation, and mass distribution all in one place.

E-commerce is one of the biggest trends of the 21st century, but its revolution is nowhere near complete. The main characteristic of e-commerce, from my perspective, is not that you get items delivered to your home. The key element that was radically different is that through e-commerce, you have a buying party and a selling party, and one of them is completely automated - it’s a machine. The radical innovation in e-commerce was literally the fact that one of the parties is just a machine. E-commerce is still growing very strongly, as we discovered in 2020, and I think it will only increase, even for types of goods where a few years back skeptics said e-commerce would only have its place for certain types of products. There were certain types of products that were considered well protected, but I’m not quite sure that anything is protected from e-commerce. Even fairly expensive goods like cars are increasingly being acquired and sold through e-commerce means, and I suspect that this will extend to practically everything.

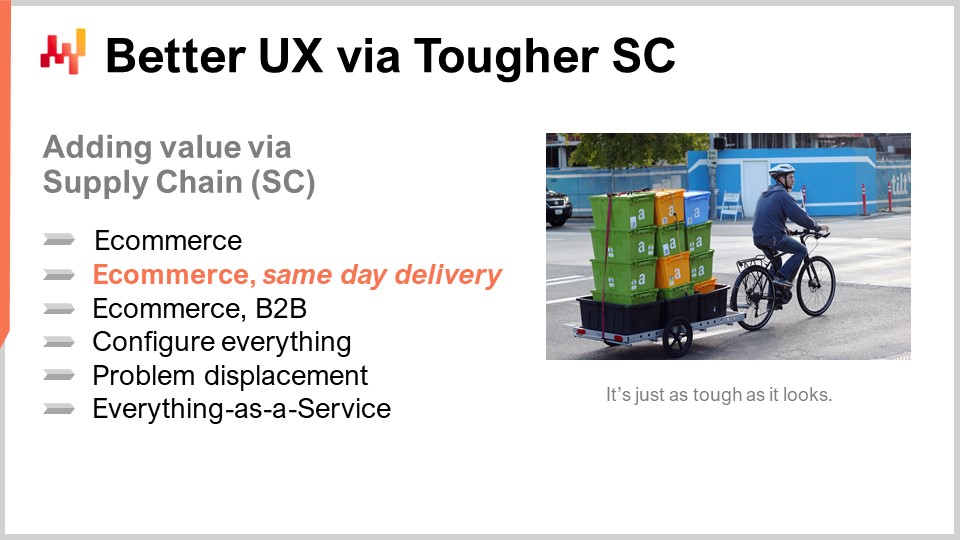

However, e-commerce is not a monolith; it has plenty of ramifications and many ways to develop superior forms of e-commerce. For example, we have e-commerce with same-day delivery, which is like e-commerce on steroids. One of the products of e-commerce with same-day delivery is a complete odd mix of super high-tech and super low-tech solutions. On the high-tech side, it’s almost impossible to achieve same-day delivery at scale without super modern information systems. You need very scalable, very modern enterprise software to be able to execute this type of supply chain at scale. But at the same time, because we don’t have delivery drones or delivery robots yet, the way we actually deliver things is through couriers, which is an incredibly low-tech approach. In this picture, the contrast is that we have one of the most advanced companies tech-wise on the planet, but if you look at the way things get delivered, it would not be completely astonishing to someone from a century ago.

E-commerce has more than one dimension; it’s not just about speed. Sometimes there are many other qualities to consider. For example, from the professional side of things, there are many other dimensions that matter. Let’s say you’re dealing with a construction site; you might be interested in having all the goods delivered directly to the construction site itself. However, the purchase order is much more challenging than if it were just a purchase order from a regular consumer because you might be ordering several thousands of units. So, you have a purchase order that is maybe a thousand times more complex than what an actual random person would order.

Furthermore, the company ordering all those goods to be delivered might ask for a very specific timeline in terms of delivery because there might not be enough space on the construction site for all the packages to be delivered on the same day. This creates tons of extra complications, and I believe we’re only starting to scratch the surface in this area. During the 21st century, these things will amplify more and more. It’s not just e-commerce; e-commerce creates many ways to add a lot of additional value for clients, but this extra value has to be paid for in extra sophistication, which in turn increases the overall entropy of the supply chain.

Another aspect is the idea that customers always want more choice. If you have a fantastic product and you have only one color, people might still choose this product in just the one color that you happen to be selling. However, if there is more choice and all things considered equal, the company that provides more choice is winning.

Configurators in supply chain are mechanisms by which customers can literally pick physical attributes for the product they’re about to buy. These configurators have been prevalent for decades in certain verticals like automotive or computers, where you can pick many options for the product you’re about to buy. More and more, I see configurators emerging in plenty of other verticals, such as bikes, home furniture, and other areas where configurators weren’t previously used. Interestingly, the need for configurators is so high that sometimes they emerge on their own without even having the support of the companies themselves.

As an anecdote, let’s consider LEGO. There are some communities and people who share LEGO models that are not official LEGO sets. These community-designed models include a bill of material, a list of parts and quantities, but they’re not directly supported by LEGO the company. Fortunately, LEGO has a web store with a specific service called Pick a Brick, where you can enter the part number and quantity to order the parts. However, if you have a community model with 200 parts, ordering this model through Pick a Brick is a nightmare because you need to manually enter those 200 parts, which is exceedingly tedious.

Some smart folks figured out a way to script the process, essentially allowing community members to share an Excel spreadsheet containing their bill of material. You log into the web store, execute the script, and it adds all the parts and respective quantities directly to your shopping cart, making the process much easier. But imagine the situation for LEGO when this happens. Suddenly, it’s not about having a few clients ordering large quantities of bricks, but an army of regular customers, each with a custom order of 200 different parts. In terms of supply chain complexity, it’s a completely different game.

More generally, one of the fundamental trends of the 21st century is that whenever you can replace a problem with a supply chain problem, the transition happens. To illustrate this, let’s look at copper tubes and plastic tubes. Copper tubes are incredibly versatile and, from a supply chain perspective, they’re as straightforward as can be. You only need something like a dozen references of copper tubes with varying diameters and a few consumables for welding. With that, you can pretty much do all the plumbing you want. Of course, I’m simplifying, but the point is that copper tubes offer incredible versatility with minimal supply chain complexity. However, this comes with one major problem: the need for welding skills. Welding is not easy; it’s a craft, and people who are good at welding are in short supply in practically every country. They are also expensive, and you can’t be absolutely sure of the skill level of a specific person unless you’re a welder yourself.

A way to displace this problem is to opt for plastic tubes that can be adjusted like LEGO parts. But suddenly, you go from having a dozen references of copper tubes to tens of thousands of references for plastic tubes. This is because you need all the lengths, angles, diameters, and potentially colors. Furthermore, plastic tubes are not as versatile as copper tubes, so you may need different tubes for indoor and outdoor use, among other factors. Essentially, you can eliminate the need for welding skills through extra supply chain complications by adopting a LEGO-style approach. However, this creates a massive supply chain problem to address because the number of references has multiplied by more than a hundred.

More generally, there is the idea that people would prefer everything as a service. For example, when you’re buying a drill, it’s not the drill itself that interests you, but the holes it creates. The same idea applies to many situations where clients are primarily interested in the benefits and not necessarily in the possession of some kind of physical product. Whenever there is an opportunity that makes economic sense, the possession of the product will be replaced by a service of some kind. This has been happening strongly in industries such as aerospace, where the notion of buying aircraft where you just pay per flight hours and flight cycles has been steadily increasing in prevalence over the last decade.

One of the biggest challenges when offering anything as a service is that the company selling the service needs to have absolute control over its supply chain execution. Otherwise, you cannot compete with other companies that are better at supply chain management and can operate more profitably at a price you cannot sustain. Moreover, if you want to simply avoid operating at a loss, you need to carefully assess your supply chain costs ahead of time. This is because you may have flat fees or pay-as-you-go payments that are not directly related to the supply chain costs you incur. Offering everything as a service has a massive upside for the client in terms of simplicity, but it requires sophistication from the provider on the supply chain side.

A second class of problems involves programmatic options, which are so complex and numerous that they can only be exercised with the help of a computer program. This has been going on for more than a decade and was characterized by the quote from Mark Anderson, a famous venture capitalist and investor, who said, “software is eating the world.” I believe this to be absolutely true, supply chain included. Let’s look at some examples of programmatic options.

First, there is the idea of having cloud-based third-party logistics and storage. These are fundamental supply chain capabilities, and in the past, acquiring them involved significant entry barriers. However, with cloud-based solutions, you can supplement your supply chain with almost no friction cost. While it may be economically more expensive than making a big upfront investment, you gain massive flexibility.

Take Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) as an example. The first-class citizen in terms of interfaces to interact with FBA is not the user interface but its API, the Application Programming Interface. If you want to interact professionally with FBA, you are essentially buying logistic capabilities and storage through an API, which is designed to be operated by computer programs. This is an example of a programmatic option that only makes sense to leverage if you have a computer program at your disposal.

Another example is robotized warehouses. There are two distinct layers of software at play here. The low-level layer only cares about the mundane execution of piloting the robots themselves, which has more to do with mechanical engineering and electronics. This is not the software and programmatic capability I am referring to. The programmatic options arise when you think about the orchestration layer. If you have a robotized warehouse, suddenly there are tons of things you could do at any point in time that would not have been feasible with a traditional warehouse. You can dynamically reorganize your warehouse according to specific supply chain strategies, taking into account upcoming promotions or anticipated demand patterns. You can orchestrate your warehouse in ways that were simply impossible before, just because the base layer is robots. The robotization of the base layer gives rise to programmatic options at the supply chain level. This is true for warehousing, but also for basic manufacturing.

CNC machines for milling or machining have been around for decades, but the software used at the production level is getting better every year. Although the computer programs needed to pilot the machines are just the base layer of the software and have nothing to do with supply chain per se, when you have production and design that becomes exceedingly agile with completely programmatic machines, your manufacturing lines become more agile. The challenge for the supply chain is to make the most of all those options. During my first lecture, I defined supply chain as the mastery of optionality. So, if you have anything that introduces more options, you need to make sure that those options are readily available and leveraged by your supply chain. CNC machines represent the progress in subtractive manufacturing, with shorter series, more agility, and more versatility in production.

But if you want to push the concept even further, there is additive manufacturing. I’m not saying that additive manufacturing will completely replace subtractive manufacturing; I’m just saying that throughout the 21st century, we will see more options become available. When you have a new technology, the old technology doesn’t go away; the two coexist with pros and cons. It means that you have all the options on the table, and depending on the situation, you can decide to use one technology or another.

One interesting aspect of additive manufacturing is that it was designed with programmability in mind. The metaphor is a printer, where you have a computer program that prints whatever you want. People don’t realize that 3D printers, although they had massive hype, are still progressing relatively rapidly. While preparing this lecture, I was surprised to discover that it is now possible to have a metal 3D printer in an office. I knew that metal 3D printers were a thing, but until a few years back, all the models that existed were only suitable for fairly industrial environments. They were not the kind of things that were safe to use in an office. But nowadays, there are some 3D metal printers that you can have in your office. It’s still a bit bulky, but it’s very impressive to witness the amount of progress achieved in just a few years. As I look through the 21st century, I see that these options will become more and more prevalent. It doesn’t mean that they will always be competitive enough to displace everything else, but it means that they offer a massive amount of options to cope with unexpected spikes in demand or variations.

However, the number of options gained is so great that you cannot realistically think you’re going to pilot your supply chain with a fleet of 3D printers without using smart software capabilities to drive all those decisions and execute them in ways that are completely coordinated with the rest of your supply chain.

Autonomous vehicles are another example. For me, there is almost zero doubt that by the end of the 21st century, autonomous vehicles will have become the dominant thing on the road. Despite the hype a few years back, I strongly believe it’s coming, as fantastic progress is being made in this area every passing year. The undertaking is quite gigantic, but cars like Waymo have already achieved superhuman performance in terms of safety. The challenge is not demanding absolute safety from these robots, but recognizing that they are already safer than human drivers.

From a supply chain perspective, autonomous vehicles introduce programmatic options. I’m not talking about the base layer of the software, which is just about piloting the car and deals with pattern recognition; that’s just the most complicated piece of having an autonomous vehicle. As soon as you have a fleet of autonomous vehicles, orchestration capabilities and options emerge, making it exceedingly desirable at the supply chain level. The day we have autonomous vehicles, there will be a massive amount of options where we can decide where to place our fleet of vehicles to better serve our supply chain needs. Realistically speaking, it’s not conceivable to have one person behind every single autonomous vehicle. If we remove the drivers, it’s not to transfer those drivers into people in some kind of call center just driving the vehicles around. You really want to have those vehicles orchestrated by supply chain software dealing with the predictive optimization of your supply chain.

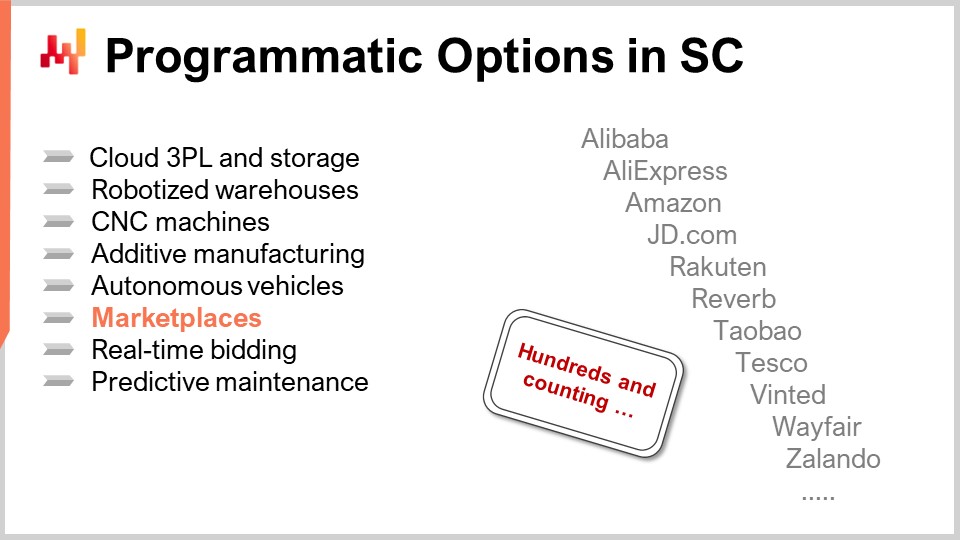

Marketplaces, for me, are an extension of the e-commerce concept. They represent places where companies can either buy or sell, which is valid on both the supply side and the fulfillment or demand side. As a general consumer of these marketplaces, you might be used to a user interface intended for humans, but from a professional perspective, most of these marketplaces offer APIs that are intended to be leveraged by professionals through computer programs. The number of marketplaces is steadily growing, and very smart companies leverage them.

It doesn’t mean that selling through a marketplace is the only way to go, but if you have a primary channel with some erraticity and you end up with a bit too much stock, having a secondary channel is better. If you have two companies, one that is not using the marketplace options and one that does, the company that plays with all the cards available to them will play the game better.

Marketplaces also allow for price discovery, typically achieved through something akin to an auction. Because the marketplace wants to operate at scale, you can’t have an auction that takes place in human time; it has to be machine time. That’s why you end up with technical challenges known as real-time bidding. When I say real-time, it’s more like milliseconds-level latency. We are entering a realm where the only way to participate in the auction is through a computer program, as these auctions are conducted within a timeframe of maybe 50 milliseconds, which does not allow for human intervention.

From a supply chain perspective, these price discovery mechanisms are of high interest because suddenly you can have a spot price for tons of things, reflecting market tension in a very short timeframe, yielding better resource allocation for the market. Obviously, the companies that are the best at playing real-time auctions through real-time bidding schemes will be more profitable compared to those that don’t play the game.

Another aspect to consider is predictive maintenance. Over the last couple of decades, electronics have become dirt cheap. Nowadays, you can have very capable computers for just a few dollars. When electronics become that inexpensive, it makes sense to add electronic sensors to any expensive piece of industrial equipment, just because you can and because it’s so cheap.

Airbus reports that a modern aircraft like the A350 has 50,000 sensors, producing 2.5 terabytes of data every day. This is an enormous amount of information. From a supply chain perspective, this information can be used to improve various aspects if you know exactly how to process and analyze it. Predictive maintenance is about being proactive, minimizing costs and downtime by knowing what to do ahead of time, not because you have a magical wand or crystal ball, but because you have data that tells you with a high degree of certainty that something is about to happen.

Predictive maintenance means that the only way to leverage these emergent options, which will likely become increasingly prevalent throughout the 21st century, is by having ways to process exceedingly large amounts of data. Modern computer systems make it possible to process this amount of data on a daily basis. It is certainly orders of magnitude cheaper compared to operating an aircraft and even maintaining it.

We have seen in this lecture that there are various options that are so complex that the only way to exercise them is to leverage computer programs. I believe that supply chains will also become even more complex throughout the 21st century for reasons unrelated to supply chains themselves.

One of these factors is social networks. We can debate whether social networks are a net good or bad for mankind, but what is certain is that from a pure supply chain perspective, these social networks add a whole new layer of erraticity to the game. Products can go viral, and demand can explode at a worldwide level in ways that were never seen before. Conversely, the damage that a brand might incur just because some moronic employee did something fairly stupid on social networks is staggering. Social networks can completely amplify a spike or, on the contrary, turn what would have been a hit for a brand into a nightmare situation. These social networks magnify the pre-existing erraticity.

Large organizations, whether or not a supply chain is involved, need bureaucracies to support themselves. Bureaucracies are the glue that brings complex organizations together, so you can’t do without them. However, one problem with bureaucracies is that they tend to grow on their own, whether they are adding value or not. Supply chains, being fairly complex and distributed, are particularly prone to the emergence of bureaucracies.

In many companies that have automated their warehouses, there are now more white-collar workers in offices operating spreadsheets than there are people on the ground physically operating the supply chain. This can be seen as the emergence of bureaucracies. Interestingly, one way for bureaucracies to grow even faster is through the appeal of novelty. Over the last few years, the fastest-growing bureaucracy in most large companies has been data science teams, which fit the definition of bureaucracy – a high class of priests doing super complicated esoteric stuff on their own, with little added value to show at the end of the day.

In addition to internal bureaucracies, there are external factors related to governments and regulations. In the mid-20th century, Milton Friedman showed that U.S. companies were subject to approximately 2,600 pages of regulation. Based on recent analysis, it is believed that nowadays, the number of pages of regulations impacting a large North American company is in excess of a million. In less than a century, we have almost multiplied the amount of regulation by a factor of 1,000. While some regulations were definitely for the greater good and a reflection of social progress, it’s worth questioning whether inflating the mass of regulation by a factor of a thousand is really a net good for humanity. The problem with supply chains is that they tend to be impacted by almost every single regulation on Earth. They are affected by labor laws, intellectual property, safety regulations, and more, as almost all regulations converge towards having some degree of impact on supply chains.

In recent years, we have seen unprecedented actions by governments, such as lockdowns. While it’s not the place to pass judgment on whether these measures were good or bad for society, they certainly were a nightmare for supply chains and added a whole new layer of complexity to handle. Unfortunately, the rising trend for the 21st century will likely be the continuous growth of regulations and interventions. Hopefully, things will plateau before the end of the 21st century, but for the next few decades, the trend is upward.

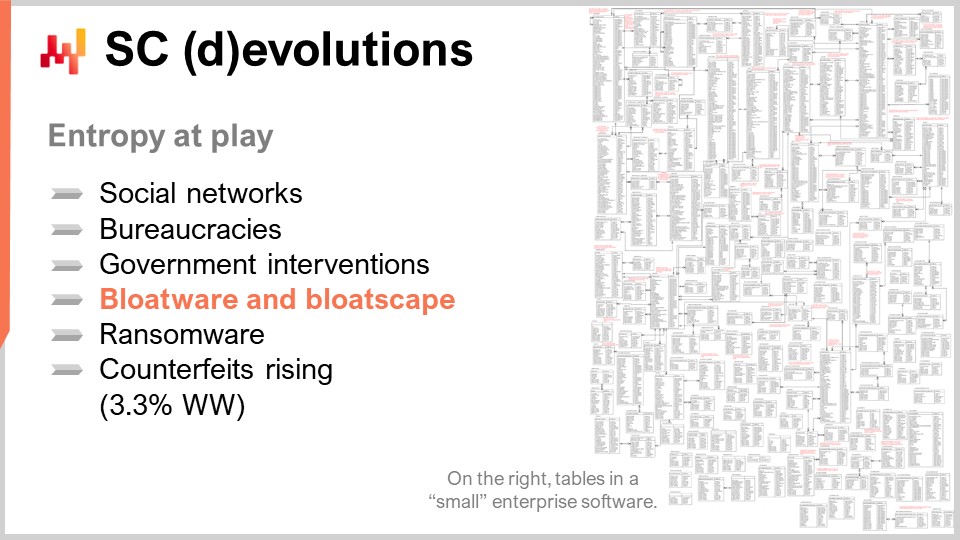

Modern supply chains are already completely operated through software. There are no more large-scale supply chains that operate using paper records – everything is digitalized. However, these software products tend to have their own inherent complexity that keeps increasing over time. One core reason is that software companies need to sell new versions of their products, and the usual tactic to do so is to add features to the existing product. The problem is that, at some point, if you keep adding features, the software may collapse under its own weight. This is what the term “bloatware” refers to.

As an example, the image on the right shows all the relational tables that exist in a relatively simple piece of enterprise software. If you were to look at what large enterprise vendors are selling nowadays, it would take something like 100 times this screen to represent all the tables and elements in their systems. I don’t believe that this complexity is completely under control. In my role as a technical auditor, in addition to being CEO of Lokad, I have seen situations where a piece of enterprise software has a massive problem of collapsing under its own weight due to completely runaway complexity. This is becoming increasingly frequent. In the supply chain domain, you end up with a forever growing landscape of applications that you have to manage, which I refer to as the “bloatscape,” where you have literally hundreds of applications.

And as a side effect of this trend of software eating the world, a new class of criminals has emerged – those who commit ransomware attacks.

In terms of computer security, the more attack surface area you have, the more exposed you are. Supply chains are in a vulnerable position by design. If you want to make a piece of software exceedingly secure, one solution can be to use air-gapping techniques, where the computer system is not connected to any network or the internet. This is what can be done, for example, in a nuclear power plant. However, this is not possible for supply chains, as they need to be connected to suppliers, customers, and many other parties by default. They are completely exposed because they are completely connected.

Furthermore, supply chains are geographically distributed by design. To serve clients worldwide at a certain scale, you need a worldwide presence. So not only is the software completely connected and networked, but it is also geographically distributed to some extent, which maximizes exposure to cyberattacks. This is why ransomware has been on the rise during the last few years. It’s one of the fastest-growing industries, and its worldwide scale is very difficult to estimate. When companies are under ransomware attacks, they usually don’t go public with it, making it a very opaque phenomenon. However, there is no question that it’s a multi-billion dollar industry, and it is growing extremely fast – with more than 50% yearly growth. I suspect that this trend will continue just because there is so much value in adding more software. Companies will keep adding more software out of necessity, as it is the right move to make. This will continue to add value, but through this process, they will be more exposed to this class of risk. Unfortunately, the benefits associated with having more software are so great that companies have to afford the extra risk that comes with ransomware. The best players will be those who have the most mastery of this class of risk.

Another issue is counterfeits. Unlike ransomware, which represents criminal behaviors that do not originate from the supply chains themselves, counterfeits are criminal behaviors that originate from players that have a supply chain of their own. In the 20th century, defense mechanisms against counterfeits were simple, such as trust. For example, in Detroit’s car industry, if a part manufacturer played any shenanigans with any car manufacturer, they would be banned from doing business for life. This created a massive incentive to be honest.

However, the problem with bad behaviors from people operating supply chains themselves is that in a complex world with many marketplaces and machine-driven interactions, there is no more human judgment to apply reputation to the actors. This has led to a class of problems that are very hard to eliminate. Counterfeits have been steadily increasing over the last two decades, now accounting for 3.3% of the global world trade, which amounts to around 500 billion dollars annually. I believe that through the 21st century, this problem will only keep growing until we find ways to address this class of bad behaviors. However, that will require solutions that have not been invented yet.

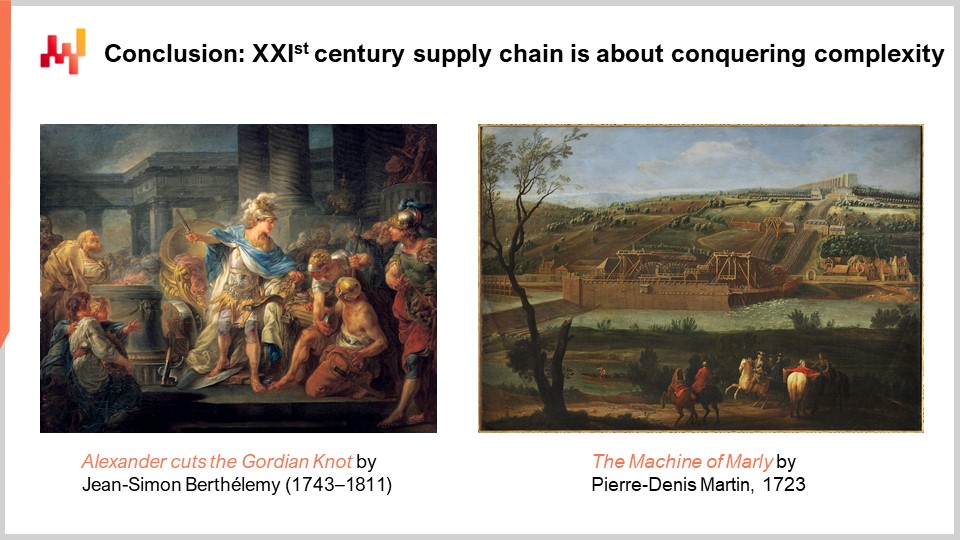

In conclusion, I believe that 21st-century supply chains will be all about conquering complexity. But make no mistake, there are really two camps in terms of complexity: accidental and intentional.

On the accidental side, the way to conquer complexity is to have the courage to cut through the Gordian Knot. It can be challenging because when you want to eliminate accidental complexity, you often shock the bureaucracies in place. Don’t expect much support from existing bureaucracies to eliminate accidental complexity; they literally feed on it. It usually requires not only acumen but also a great deal of courage.

Then we have intentional complexity. An illustration of this is the Machine of Marly, which was designed for Louis XIV, King of France. The purpose of this machine was to bring water from the river to the Chateau of Versailles. This machine was remarkable for being considered the most complicated machine ever built at the time and also the loudest. The complexity was staggering for the time, but it was also completely intentional. We just didn’t have any better ways to address the issue.

When it comes to intentional complexity, the only way to master it is through superior technology that can make the complexity go away because you have better tools and technologies to embrace the problem and provide simpler solutions for them.

That’s all for today. Thank you very much for your attention, and now I will be jumping to the questions.

Question: What is the Lokad value proposition?

I believe the Lokad value proposition is to be a dominant actor in the 21st-century supply chain.

Question: How do you think industries should benchmark the time that should be taken for procurement, production, and deliveries? How should they measure whether it’s an appropriate near-to-ideal time? Is there any scope for improvement? What is the targeted goal, and how can it be measured?

First, I would challenge the very notion of benchmark. The idea is that if you want to benchmark, it means you’re just like the guy next door. Do you think that Jeff Bezos thought about doing benchmarks when he did Amazon? He wasn’t trying to be as good as Walmart; he was focused on crushing the competition. The problem with benchmarks is that they can be underwhelming and reflect a complete lack of ambition. Instead, you should aim to redefine the state of the art and what excellence means within your vertical.

I’m skeptical about the idea of benchmarks, as they can be misleading. It’s unclear if the competitor you’re comparing yourself to has the same quality or if they’re cutting corners in ways you don’t realize. Perhaps they’re taking risks with regard to counterfeit goods in the supply chain because they don’t properly vet their suppliers. The grass tends to be greener on the other side, but companies should focus more on their own clients and how they can improve, disregarding what the competition is doing.

Exceedingly successful companies often don’t care about what the rest of the market is doing; they just do what they think is best and usually crush the competition because they’re the ones paying attention to their customers. To improve, focus on the angles that will really make you better. One of the key ingredients is a financial perspective, which allows you to balance the various forces at play in supply chain problems that involve trade-offs.

Question: When it comes to B2B problems in supply chain and classifying them into the 6M fishbone models, how do we address the problems related to the availability and scale of skilled labor in a B2B e-commerce setting? Moreover, how do we measure the impact of manpower?

Supply chain, as I define it, involves the mastery of optionality. This statement suggests that supply chain success requires excellent players. While there are plenty of areas where having excellent or average players doesn’t matter, supply chain isn’t one of them. For example, no company will crush the competition because they have superior accounting. At best, they could have good accounting, but it doesn’t matter if they have absolute geniuses in the accounting department. While it might make a difference, there are many functions in a company where what matters is just to have something reasonably average, and that’s good enough. Having better than average will not yield any tangible benefit for the company. I believe that supply chains in the 20th century were this sort of game, which was also the topic of my first lecture.

In the 20th century, the game was played at the branding and production levels. You needed to have superior branding and production to conquer the world, and that was the success of companies like Mars, Unilever, and Coca-Cola. However, in the 21st century, with developments like e-commerce, you need excellent supply chain execution to win. The thing about supply chains is that they are not a game played directly; they’re played indirectly via software. Software is a massive magnifier of individual talent.

For example, even the best player in a certain field can only do so much. I was recently reviewing statistics about the best car salesman in America, who sold five times more cars than the average salesman – an impressive feat, but not that much compared to software. In terms of software, you have people who deliver a million times more than the average person. Software magnifies talent in ways that were never seen before.

When it comes to B2B problems in the supply chain and manpower, you should stop thinking about manpower in the traditional sense. No software company measures success by the number of software engineers they have. What matters is having absolutely stunningly brilliant software engineers – it’s a game of talent. So, the focus should be on talent rather than manpower.

When it comes to attracting talent, ask yourself how you can make the most brilliant minds of your generation want to apply for your company. This is a key challenge. By the way, that explains why companies that know the war is fought on the talent front, such as Google, who are very good at this game, are actually making their deep learning technology and AI tech open source. You might think it’s crazy to make the crown jewel of their tech open source, but the reason is that by exposing this technology to the greater world, it acts as a magnet for the most brilliant minds of the generation. It’s a very smart move from Google, and it doesn’t matter if they give this technology away to competitors, because what they really care about is grabbing the talent to outcompete hiring-wise.

Alex suggests that tackling 20th century challenges requires technological talent, but most companies and brokers are lacking people of this kind in decision-making positions. What does it mean for most Fortune 500 companies? Will they disappear? When you make the statement that most large companies are made of bureaucracies, it wasn’t always the case; it gradually became so. When you look at Fortune 500 companies, you’re looking at relatively old companies with ongoing growth of bureaucracies.

So, how will the problem sort itself out? It will either be through market Darwinism, where those companies collapse under their own bureaucracy and are replaced by fresher, younger companies where bureaucracies didn’t have time to grow, or it will be part of the undertaking of the 21st century. We might figure out ways to put those bureaucracies under control through scientific methods or other approaches, understanding the dynamics of organizations and supply chains.

If you’re in such a company, invite your management to have a look at this lecture and have the courage to take a turn in the company’s strategy. Realize that they need to re-challenge in-depth the way they are doing business, and it’s not a matter of being marginally better; it’s a matter of survival if you look two decades ahead.

Question: So all those programmatic options and outsourcing options would be suitable for those firms with investment capital already in place. What would you recommend for startups to build this in-house?

First of all, those programmatic options have incredibly low barriers to entry. With things like FBA, you can rival super established supply chains with almost no upfront capital. Of course, you can’t challenge them on a cheaper supply chain front directly; you have to be smarter about it. You need an angle, like marketing or branding. Make no mistake, these options are not favoring the large and established; on the contrary, they are a massive boost to the small and agile.

Just imagine you’re in the mid-20th century and want to compete against General Motors. It’s not possible. The established car manufacturers are completely entrenched. Tesla was only possible in the 21st century because all those options became possible and loosened the entrenchment of established players. These options are available for everyone, but small companies with higher talent density have a massive advantage when it comes to making the most of those options.

For startups, I don’t recommend building anything in-house if you can outsource it to a third party. As a startup, you need to pay attention to your clients and choose your battles carefully. If your battle is to deliver the most fantastic appliance for your home, then you don’t want to outsource that. But everything else, like web hosting, logistics, and storage, if it doesn’t contribute to your core value, especially as a startup, don’t be afraid to outsource pretty much everything except your core. Choose your battles wisely.

Question: With 3D printing becoming commonplace, how soon do you think manufacturing itself would become outsourced?

I believe that 3D printing is already quite commonplace. For example, in industries like aerospace, there isn’t a single aircraft being produced without thousands of parts that are 3D printed. I’m not sure about the automotive industry, but I believe 3D printing is already widespread. It’s not dominant, and it might never be dominant in terms of the mass of products, just because the mechanism by design, 3D printing, is maybe not, at least with the technologies that we have right now. Even if we are making progress, they don’t compete; they can’t compete frontally on costs with just subtractive manufacturing. Nonetheless, I believe that they will be ubiquitous in the sense that why would you have to pick a side? 3D printing is so cheap, so it can be made super cheap. So even if your business is dominantly serviced through subtractive manufacturing, it is very reasonable to have additive manufacturing as a way to supplement your subtractive capabilities.

The thing with those printers is that they are very easy to distribute all over the place. That’s why I was mentioning the idea of having metal 3D printers that you could have in an office because, obviously, if you could have them, those printers in an office, it means that you can literally have those printers anywhere. That’s very interesting; it means that you could literally distribute a small fraction of your production capacity to have the capacity to serve markets according to very special needs just in time and maybe even rent your production capacity to other places because, you know, if you have marketplaces, you can have marketplaces where people just rent their 3D printing capacity to manufacture anything, not just the thing that they usually serve.

Question: Coordination and consolidation between various software interfaces across several tech suppliers: a challenge towards optimality for most of the programmatic options. What are your thoughts?

So, coordination and consolidation: there is this old joke in the software industry where you have 10 software standards, and the software engineer looking at the problem says, “Oh, there are so many standards, it’s a very bad situation. I think I’m going to unify all those standards and make one that subsumes all the others.” And a few years later, there are 11 competing standards. The problem with standardization is that it’s very hard to achieve, especially when it comes to software. There are not actually strong incentives for all the people to come together and have completely compatible things.

Keep in mind that if you have superior programming paradigms, it means that tackling a diverse set of problems that have the same characteristics might not be as complicated as you think. The fact that software standards are not completely aligned or consistent, if you have the right programming paradigms, most of this complexity can be abstracted away. It’s not something that is as impacting as it appears at first glance.

Another thing is the idea that you can converge toward optimality, and that was something that I addressed during my first lecture. Supply chain is a class of wicked problems. So, I would say be very wary of thinking that you can be optimal in any way. This is not a sort of game where you can play optimally. What you can do, and again, back to the first lecture, is just be better than what you are presently. That is possible. Being optimal, I don’t even think that it’s an applicable concept as far as supply chains are concerned.

Question: Shouldn’t blockchain initiatives run somewhere or conserve?

The funny thing with blockchain is that there’s an old joke and a Lokad TV episode about it. My belief is that people who use the term “blockchain,” especially when they pretend to be experts on the subject, only demonstrate one thing: that they know nothing about it. Blockchain is just a completely non-interesting piece of technology in my eyes. Decentralized electronic currencies, however, are absolutely fascinating. Can electronic currencies do something about counterfeits and ransomware? For ransomware, I would say absolutely not. On the contrary, electronic currencies have become the biggest enabler of ransomware. It’s adding fuel to the fire, making the problem worse. Adding blockchain in the middle of the supply chain is just going to add a massive mass of technology that will also make the problem worse. The answer is no, absolutely not.

Can it improve the situation on the counterfeits front? Yes, but in ways that are very counterintuitive. I will give you a reference to a paper I published a few years back on a scheme called Tokeda. You can improve the situation on the counterfeits front through decentralized electronic currencies, but the solutions and assertions that are proposed are nothing like what you would imagine. So yes, but it’s going to be fairly weird.

Question: What about the shift in sustainability initiatives? Reduce consumption over time, increase reverse logistics. Do you think this will be a big factor in the coming years?

There are several angles here. First, reverse logistics is exactly what I was discussing. It’s another example of better user experience through a more sophisticated supply chain. People want to be able to try products, not just buy them. If they can try, it means that sometimes the try will fail, and they will send the products back. Or they have other reasons to send the product back, maybe because they are just renting the product in the first place. Reverse logistics is the sort of thing that adds value through sophistication. I think you’re spot on; this will play an increasingly important role in supply chains. If you don’t do that, there will be competitors that do, and you will be outcompeted on the user experience front, which is very bad because that’s what earns you customers.

Now, on the sustainability front, such as reduced consumption over time, it may shock you, but I am not such a believer in sustainability for itself. I am a big believer in economic optimization. Why? Because if something is not sustainable, something is not sustainable, if you’re trying to consume a material that becomes rarer and rarer over time, then the rarity of the thing is just going to reflect itself in the price. You will be depending on something that is increasingly more expensive. By the way, this is exactly what I pointed out in my example with copper tubes versus plastic tubes. If you’re only using copper tubes, you’re depending on something that is increasingly rare, which are welding skills. If you want to be sustainable in this business, you better have a plan B, such as plastic tubes, where you don’t depend on something that is becoming incredibly scarce and unsustainable.

In the end, that’s why the quantitative supply chain perspective discussed in the second lecture is the best way to assess whether something is sustainable or not. You should look at the cost, not just the costs that you incur today, but also what you can project upon. If you see that you can do something that looks super cheap but you’re taking massive risks, for example, massive environmental risks such as spilling oil all over the Gulf of Mexico, you’re not doing a service to your company. It’s not cheap at all. It is probably one of the most expensive ways to operate your supply chain if you are taking such environmental risks because there will be a problem given enough time, and the company will have to pay the bill ultimately, which can be staggeringly expensive to the point of bankruptcy.

Question: How can medium-sized businesses avoid falling into the trap of bloatware when trying to reduce mundane work and approaching third-party vendors, which are experts in their niche segmentation, such as evaluating vendors for digitalization of purchase invoices from suppliers using AI-based OCR technology?

When it comes to software vendors, there are good guys out there. There are software companies that know that if they play the bloatware card, their product will be toast one decade from now. I believe Lokad is one of those companies, but there are plenty of others. When you approach vendors, I suggest having a general chat with the people from those companies. I’m assuming an enterprise sort of deal, where you can actually discuss with the vendor, not the kind of software where it’s super cheap, and you just tick a box, buy a license, and here you go. Assuming that we are talking about an enterprise type of software where it’s expensive and you have to talk to the vendor, my suggestion is to ask simple questions about the core design principles at the heart of their software product.

First, if people have no clue whatsoever about core design principles, you can be sure that it’s bloatware because it means that they have no clue about what they’re doing. If they tell you something that kind of makes sense, then it’s already a very good sign. Keep in mind that it’s not about having the optimal solution; software and supply chain are wicked problems, and there is no such thing as an optimal solution. What you can have is just a solution that is vastly superior to what your competitors are doing. If you can usually pick up the good guys in terms of software companies, focus on companies that really concentrate on delivering good products based on solid foundations, where the complexity is kept under control. Avoid vendors who just want to tick as many boxes as they can. For example, be very skeptical when you meet a vendor that seems to tick all the buzzwords of the day: AI, blockchain, big data, machine learning, etc. Be very skeptical; it usually means that they have no principles whatsoever because they didn’t make any choices in terms of technology. They just glued everything together without any consideration for the technological mess.

Question: As efficiency grows, fewer jobs should be required in the future, at least in theory, because of automation. Do you think we’ll face some social issues that may indirectly impact supply chains?

I believe that it’s a very widespread but profoundly misguided opinion. I think it is human nature to have no limit to what we want; we always want more. The dominant pattern in the human race is the desire for more of everything; there is no limit for that. Yes, you have automation, but consider this: Here in Paris, two centuries ago, the biggest job was water carriers, people who carried buckets of water. That was the number one job that kept people busy. All of that has vanished to nothing. Are we poorer because of that? No.

Automations lead to creative destruction, as pointed out by Joseph Schumpeter. It’s the way societies become richer, and when I say societies, I mean everybody in society, from the bottom of the pyramid to the top. Everyone gets richer when you achieve a higher degree of automation. People at the top tend to be even richer, but everybody rises, even those at the very bottom.

What I see is that there is no limit to the desire to have more stuff. For example, I have a 10-year-old daughter, and I’m still pretty shocked when she goes to school. She is in a classroom where there are routinely between 25 and 30 children sharing one teacher. I don’t see why we couldn’t have a society where we decide that we have one teacher for every five children. If we can liberate tons of people who don’t have to operate as couriers for Amazon, why couldn’t those people be more available to take care of the young, take care of the elderly, and do tons of other things like developing the arts or whatever? So, you see, I think the simple fact that there is no finite amount of wants means people always want more, even if it’s better care for children at school. Because there is no limit, whenever you automate jobs, unless there is regulation in place that prevents those people from getting a new job, naturally, they will converge to where there is still more demand, and there is always more demand. I don’t think there is a limit. If every single elderly person could have their full-time assistant to help them in their daily life, they would choose that option. I don’t think many people would refuse this kind of offer if it was presented to them.

Now, regarding supply chain metrics and quantitative data being furnished by financial team members, the finance team should certainly have their way to shape what I would refer to as the economic drivers. For example, when it comes to the cost of capital, the finance team should decide what the cost of capital is, not the supply chain team. However, for every single driver, we need to decide who is responsible for establishing a proper metric and how to measure it in dollars or euros. If it’s the cost of capital, it’s going to be the finance team. But if we are talking about stockout penalties or penalties incurred when we do a disservice, maybe marketing should be responsible. I don’t think there are any absolute rules on who is supposed to be responsible, but maintaining ambiguity could lead to massive friction. My suggestion is to decompose the economic drivers and make sure that for every facet of the problem, there is one team that is the final decision-maker. Obviously, the CEO acts as the ultimate arbiter if there is a team that is not making sense.

Question: I know many firms have software but don’t utilize it for their supply chains. Can you recommend a cost of failure of adoption, a cost of under-utilization of digital resources?

This point was actually covered in my third lecture: why are we facing a situation where there is so much software all over the place that is not used? The answer is that the software doesn’t exhibit the right properties. It’s a sunk cost fallacy when you say it’s underused. No, it’s not underused; the investment was a bad investment in the first place. So, you should not try to recoup a bad investment. This is a sunk cost fallacy. The investment has been lost; you should say, “Okay, this software is just not what my company needs. Forget about it, it’s toast, bury it, and move on.” Don’t think of it as an underused asset. In supply chain, what I usually see is either software that is spot on and used for everything or software, especially in the area of predictive supply chain optimization, that simply does not deliver any value and is indeed underused. The reality is that some of these software solutions are pieces of junk and will never deliver anything. Forget about this investment; it was a bad investment. You don’t have to be tough on people; you just have to be tough on the problem and acknowledge that this is a loss and move on.

Question: What’s a prescriptive method to combat all the punctual risk at play because of supply chain devolution levels?

To a certain extent, for the evolution, it’s not up to you. You can try to lobby your way into Washington or Brussels, but frankly, for most companies, the state of regulation is just what it is. You don’t get to choose; you have to play by the rules, and it’s the same for your competitors. The same goes for social networks; you don’t get to choose whether Instagram exists or not – it just does, and that’s a new reality, and you have to face it head-on. There is not much that you can do, except in areas that are really under your control, like processes and bloatware.

The first thing you can do is establish a culture where there is an understanding of the problem. I recommend reading Jeff Bezos’ memos about the “Day One” mentality. Behind the Day One mentality is the understanding of the impact of economies of scale and the impact of bureaucracies on large organizations. Bezos has done everything in his power to mitigate the problem at Amazon, and it contributed to a large extent to Amazon’s success. But even Amazon has dysfunctional bureaucracies at the present time. You can only mitigate them; you can’t negate the problem entirely, at least not yet.

Question: Would you say any optimization technique, like mixed-integer linear programming or non-linear programming, would be impractical for application to industry scenarios? Wouldn’t the method make room for improvement in the present situation?

Mixed-integer linear programming and non-linear programming techniques have been around for more than four decades, and there have been numerical solvers. For the wider audience that might not be familiar with these tools, they are a generalization of linear solvers or things close to linear forms that can be quadratic forms as well, where variables are integers. They were extensively studied during the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s and did marvels when it came to some very tame problems, such as component placement for designing a cell phone. However, for wicked problems, not so much.

The problem with these techniques is that they are not super expressive, despite their name having “programming” as a keyword. In terms of programmatic expressiveness, these techniques are fairly weak by today’s standards. Their expressivity is slightly more than just a linear function but not much more. Even worse for supply chains, these techniques do not play nicely with erraticity or randomness. They assume that the problem is static and deterministic instead of stochastic. If we go back to earlier lectures, where I emphasized embracing uncertainty, it means that the tools and techniques you use, including at the algorithmic level, need to be compatible with situations where uncertainty and randomness are involved.

In terms of optimization, that’s why I am personally much more convinced that differentiable programming is better suited to deliver the numerical optimization that is relevant to supply chains compared to mixed-integer programming.

Question: Which inventory control theory will be used in the future to reduce supply chain costs in the steel manufacturing industry?

Frankly, I just don’t know. The steel industry is very specific, and it depends on where you are in the supply stream. You have people who deal with steel by the ton and those who work with it by the nanometer, which presents completely different sets of problems.

In terms of theory, I believe that the current supply chain theory is deeply unsatisfying. My hope is that decades from now, a descendant of the ideas I presented in these lectures will be more relevant. That would mean that I was at least partially correct. However, I don’t think there is a valid, relevant supply chain theory at present, and that was one of the core motivations that led me to do this series of lectures. I was profoundly dissatisfied with the state of affairs regarding supply chain theory. What we have right now in terms of intellectual tools to think about and execute solutions for these problems is just not good enough. We need better tools.

In response to the question about applying supply chain technology to a political game, I don’t think it can be applied directly. Supply chain is one of those classes of wicked problems, but there are many other problems that are wicked as well. Political battles and winning elections are another type of wicked problem, and they are even worse than supply chain issues. Supply chains are fundamentally games where, if everybody plays well, everybody wins. They are wicked, but there is room for growth and increasing the net worth of everyone involved. If done well, it creates wealth for everybody. Of course, there will be winners in the sense that some people grow even faster than others, but in the end, it’s a game that is profoundly beneficial for mankind.

Political games, on the other hand, are zero-sum games. If you win the election, another candidate must lose. It’s not because you developed a set of technologies to address one wicked problem that these technologies can transpose to entirely different problems. Maybe some ideas I presented happen to be relevant for the political arena, but frankly, I just don’t know. My focus is really on supply chains, which are already vast and complex.

As for the question about an SMB retailer moving away from the min-max approach, min-max in itself says nothing. If you have a piece of software that can update your min and max in real-time for anything arbitrarily different, then almost any other ordering policy can be framed as a min-max policy. As an SMB, my suggestion would be to make sure your core software infrastructure plays well in a programmatic world. If you have to pick one ERP to run your company, make sure it comes with polished APIs, so that whatever the limitations of the ERP are, you will be able to supplement those limitations by plugging something else on the side.

Don’t think of your software pieces as just pieces of a puzzle; think of them as extensible. Extensibility doesn’t mean that the vendor is capable of selling you the extension you need. Instead, think small and choose a piece of software that is easy to maintain and lends itself to extensibility through APIs. This approach will help you future-proof your company.

In response to the question about optimization techniques in unification with system dynamics that incorporate randomness, absolutely, you want techniques that embrace uncertainty and randomness. Mixed integer programming was just an example. You want numerical optimization techniques that play very well with stochastic phenomena, where randomness is omnipresent. Some techniques play very well with these sorts of patterns, while others do not. Differentiable programming plays very well, but it’s not actually the end game. There might be other, better ways that I don’t know or that haven’t been invented yet.

That concludes the long series of questions – about 20 in total. Thank you very much for your attention. The next lecture will be in two weeks, and I will present quantitative principles in supply chains. Thank you very much for your attention today, and have a good day. Goodbye.

References (Q&A Session)

- Tokeda whitepaper, Joannes Vermorel, 2018 (blockchain use case to fight counterfeits on page 28), (pdf)