00:50 Introduction

02:22 Book by Claude Bernard

11:19 The story so far

13:39 Supply Chain Experiments?

19:21 Experimental methods: against case studies

20:50 On Big Names

28:14 On Taboos

35:05 On Job Prospects

37:51 On Pseudo-neutrality

42:59 On Vendors

45:57 Experimental methods: pro personae

46:54 Fiction vs Reality

52:19 Crafting a supply chain persona

55:26 Rejection criteria

01:02:33 Problem vs Solution, 1/3

01:08:53 Problem vs Solution, 2/3

01:11:41 Problem vs Solution, 3/3

01:16:13 Upcoming personae

01:17:06 Conclusion

01:18:29 Upcoming lecture and audience questions

Description

A supply chain “persona” is a fictitious company. Yet, while the company is fictive, this fiction is engineered to outline what deserves attention from a supply chain perspective. However, the persona is not idealized in the sense of simplifying the supply chain challenges. On the contrary, the intent is to magnify the most challenging aspects of the situation, the aspects that will most stubbornly resist any attempt at quantitative modelling and any attempt piloting an initiative to improve the supply chain.

In supply chain, case studies - when one or several parties are named - suffer from severe conflicts of interest. Companies, and their supporting vendors (software, consulting), have a vested interest in presenting the outcome under a positive light. Moreover, actual supply chains typically suffer or benefit from accidental conditions that have nothing to do with the quality of their execution. The supply chain personae are the methodological answer to those issues.

Full transcript

Hi everyone, welcome to this series of supply chain lectures. I am Joannes Vermorel, and today I will be presenting “Supply Chain Personae.” For those of you who are attending the lecture live, you can ask questions at any point in time via the YouTube chat. However, I will not be reading the questions during the lecture; I will be coming back to the chat at the very end of the lectures to answer, if possible, all the questions that have been raised.

The topic of today is whether we can elevate the study of supply chains as a science. One might object that supply chains are first and foremost a business and a practice. Absolutely, but the question is, can we bring improvement to supply chain management, and if so, can we do that in ways that are systematic, reliable, and somewhat controlled? I believe that it’s only feasible via something that would be kind of akin to a scientific method applied to the knowledge that we have.

In order to bring improvement, we need knowledge, and we need to have high-quality knowledge. What do I mean by high-quality? It’s knowledge that can be characterized by what usually characterizes scientific knowledge nowadays. If the only thing we have is intuition, then it severely limits what we can hope to be able to bring to supply chains in a systematic fashion. The scientific method is really of high interest, and being able to elevate the study of supply chains as a science is of crucial importance. But that begs the question: what is science, and what is the scientific method?

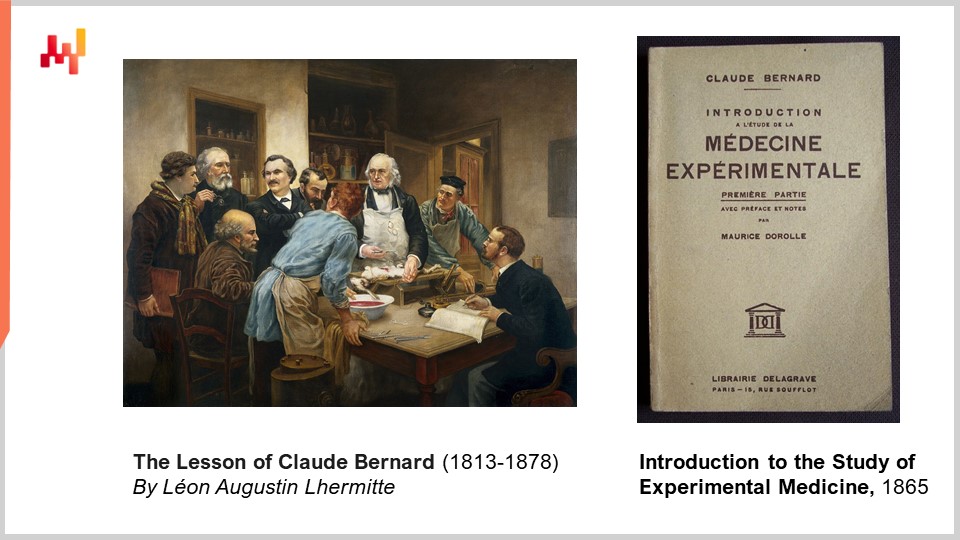

I believe that there is one book, “An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine,” published by Claude Bernard in 1865, that is an absolute landmark in the history of science. Claude Bernard, a very famous researcher at the time, is still considered nowadays as one of the key fathers, if not the father, of modern medicine by many people. Due to some illness, he went into a retreat, and he reflected on a lifelong pursuit of knowledge. He started to put in writing his ideas about how he had managed and what sort of methods he had used during his career to make all the discoveries that he had made.

This is an absolutely fascinating book. It reads like a novel, which is very surprising. It’s completely unlike the “Principia Mathematica” of Newton, which is almost insufferable. This book is very straightforward to read, at least in French. I don’t know about the English version, but I suspect that good translations exist. With a lot of clarity and simplicity, Claude Bernard explains and gives many clues about science and the scientific method. It’s something that is profoundly enlightening for supply chains.

By the way, despite the title of this book, which seems to be very much centered on medicine, most of what Claude Bernard described is completely non-specific to medicine. This book had a profound influence on many other sciences well beyond medicine. To understand why, we have to understand that in the 19th century, Claude Bernard was fighting opponents who were completely opposed to the idea that medicine should, at least in part, become a science. Indeed, the study of medicine is facing two very key challenges, which I believe are also of prime relevance for supply chains.

The first challenge is that living beings are incredibly and irreducibly complex. If you have a living organism, you can’t just apply some kind of divide-and-conquer approach; you can’t take the thing apart to study it because if you do that, you just kill the living being, and you’re left with something that is not alive anymore. That completely misses the point of what you’re trying to study. This irreducible complexity and the fact that you have something super complex that you cannot easily take apart also apply to supply chains. If you have a supply chain made of suppliers, plants, warehouses, distribution centers, and stores, and if you remove any one of those elements, the supply chain doesn’t work anymore, and it doesn’t even make sense anymore. You can’t even study it as a supply chain anymore. So, we have this kind of irreducible complexity that very much applies to supply chains as well.

The second big challenge is that a living being is essentially an entangled system. If you start making a little local change, chances are it will have impacts on the entire organism. For example, you can make a very local injection of poison, but that’s going to have an impact on the entire organism, not just the one spot where you actually injected the poison. This also resonates a lot with supply chains because, as I described in one of my previous lectures, most local optimizations in a supply chain merely displace a problem somewhere else in the network. So, we have these two problems, and at the time, Claude Bernard was facing opponents who were basically saying that medicine, due to these issues, is irreducible and cannot be reduced to something as vulgar as a science. Claude Bernard, along with many other people and those who followed, proved this perspective completely wrong. However, it’s interesting that this challenge still exists, and I believe that even a century and a half later, we are still in this phase as far as supply chains are concerned.

Now, if we want to understand what Claude Bernard brings first and foremost, it’s the idea of experiments. In his book, he puts forth the idea that our knowledge goes through three stages: emotion, reason, and experiment. The idea is that the scientific method starts with an emotion, a spark of will, that gives you some kind of preconceived idea about the universe. Through this emotion, you can start doing anything, even though it is profoundly irrational and has no scientific qualities. Without that, you don’t have the initial impulse that will trigger the rest. The initialization of this system of knowledge is emotion, and then you have reason. Reason gives shape, structure, and direction to this idea so that you can start acting. At this point, you have an idea, but it’s not clear whether it’s true or false. It just exists, but it has more structure to it than the first stage, which was just emotion.

Through reason, you can build the first stage of an experiment. The idea is that through reason, you’re going to put your idea to the test. You have this preconceived idea about the universe, and you’re going to carry out an experiment that will let you test the idea. The interesting thing is that you have to believe in your idea, otherwise, you’re not going to pursue all the efforts and time it takes to actually conduct the experiment. The scientific method is not the elimination of prior belief; this is absolutely not the case. You need to have something that is driving you, those preconceived ideas that will guide your action.

Then, you conduct the experiment, observe the results, and let the observation take control over your ideas. You had your preconceived ideas, you carried out the experiment, and then once you’ve done your experiment, you let what you’ve just observed take control of your ideas, and that will be the establishment of knowledge. One of the profound ideas within experimental science is that there is no knowledge within us. We have emotions and some innate capacity for reason, but all the knowledge there is to be found is outside of us. Even if it’s self-evident now, during the 19th century, it absolutely wasn’t. As far as supply chains are concerned, it’s not crystal clear that everybody is aligned with me on this point. The idea of having an experimental science is about constructing and extracting knowledge from the universe, and the elementary step to do that is a series of experiments.

In my last lecture, I concluded the first chapter of this series of lectures, which was the prologue. In the prologue, I presented my views on how to approach supply chains in the first place. I defined supply chain during the first lecture as the mastery of optionality. I also presented views that were both qualitative and quantitative in nature just to give you a taste of the way I am approaching the problem. In these present lectures, I’m opening a second chapter: the methodology. If we want to improve supply chains, we need knowledge to direct our actions. If we want to have a reliable way to bring improvement and have reasonable hope for a high degree of control, then we need this knowledge to be solidly grounded. I believe we need something akin to the scientific method. When I say the scientific method, I’m abusing the term, as there is no such thing as “the scientific method.” There is actually a wide series of methods, and Claude Bernard, in his book, presents a series of them. Bernard also demonstrated that science progresses not only through better theories but also through better methods. The challenge is not only to know more about supply chains but also to establish foundations with methods that prove themselves to be superior in generating better knowledge, faster, more reliable, and more accurate. The point of a supply chain is to have one method, among many, to connect supply chains as a field of study with what is happening in the real world and leverage the information that is not within us but in the world out there.

The way to bring a dose of reality into your field of study is typically through experiments. However, in the specific case of supply chains, it seems that supply chain experiments are quite complicated for several reasons. Let me present them briefly.

The first reason is confidentiality. As we have seen in a previous lecture, a supply chain cannot be observed directly; it can only be observed indirectly. The only things that you can observe in a supply chain are the electronic records that are collected and gathered by a piece of enterprise software. This is the way you can observe a supply chain, through the records collected by enterprise software or through datasets. The problem is that companies are not willing to share these datasets, and there are very good reasons not to be willing to share them. First, it’s a competitive advantage, or rather, if they were to publicly share this data, it would be a competitive disadvantage because their competitors could take advantage of having access to this data to gain a competitive edge against them.

But that’s not the only reason. There are also good reasons not to share data, such as privacy and confidentiality. For example, in Europe, we now have GDPR as a regulation. I’m not discussing whether GDPR is a good thing or a bad thing; I’m just pointing out that even if a company were willing to share its data, it would be at risk of doing something that would be illegal. As anecdotal evidence, last year, the M5 forecasting competition took place, based on sales data obtained from Walmart. To my knowledge, it was the largest, most comprehensive dataset relevant for a supply chain experiment that was ever published. Just to give you an idea of the scale of the problem, this dataset was only the sales data from a small fraction of the products of a single store. Walmart is a gigantic company that operates over 10,000 stores, and the dataset from the competition on Kaggle was not even one entire store. It was actually a small fraction of a store, and it was basically the sales history, including the history of sales in quantities and prices. To make the problem even worse, due to engineering problems in terms of data extraction, it turned out that half of the dataset, which consisted of prices, was not even exploitable for the purpose of the competition. None of the winning teams that landed in the top 10 of the competition managed to make use of this data. This gives you an idea of how difficult it is to communicate publicly on this topic, but this is not the only problem.

We also have the problem of replicability. For instance, discussing with several of Lokad’s clients in January 2020, e-commerce in their respective businesses was about 30% of the volume. By January 2021, it had increased to 60%. Obviously, there has been a whole year of the pandemic, and some relatively unprecedented things happened, which completely changed the landscape in many industries, likely forever. This is a significant problem because replicability is at the core of experimental sciences. But if you do anything in supply chain and want to replicate it, the landscape might be so different a few years later that you won’t have any hope of replicating anything. That’s another class of big problems that we face.

Additionally, there are the costs and delays involved. As a rule of thumb, a supply chain experiment would need to be at least twice as long as the characteristic lead time of the company. In many industries or verticals, the characteristic lead time is around three months, which means the characteristic delay for a supply chain experiment would be six months or longer. This is very long, and there is good reason if experimental sciences, such as experimental medicine, tend to favor using mice for experiments due to their fast metabolism and rapid reproduction rate. Time is of the essence, even in medicine, and it’s pretty much the same in supply chain. Yet the characteristic time of experiments is very long.

Furthermore, we have the non-local element we discussed previously, where it’s challenging to do a small-scale, low-cost experiment because it’s all about network effects. You can’t just do something in one place and expect results. As a rule of thumb, you can’t conclude anything from a local experiment in supply chain.

Obviously, I’m not the first to realize that we have this big series of problems and that supply chains resist the naive experimental approach. As a result, a large portion of the studies done in supply chains default to an alternative to the supply chain experiment, which is the supply chain case study. The idea is simple: we want to connect supply chain as a field of study with the real world. We want to inject doses of reality into our theory. This is what a case study is about. My proposition for you today is that case studies are glorified infomercials, and if we have to assess case studies in terms of how much knowledge there is to be conveyed by this format, my answer is approximately zero. However, all is not lost, as there are possible alternatives, and that’s where I will be introducing supply chain personnel. Due to the prevalence of case studies, we must first understand why it simply doesn’t work, cannot work, and will, unfortunately, just never work.

A case study is one company, one problem, one legacy solution (which is the solution in place before the case study begins), and then a newer, better solution. The case study describes all of that and quantifies the benefits the newer, supposedly better solution brings to the company. The biggest problem I have is that whenever I see case studies and how people reason about them, what really dominates is not the numbers present in the case studies, but the name of the company that is the subject of the case study itself. There is a massive halo of authority at play here.

Let’s imagine a supply chain case study that emanates from Google, a tech giant. Google has a fairly large supply chain of its own just to deal with all the computing hardware distributed worldwide to support its data center operations. Let’s imagine this case study demonstrates the superiority of a specific supply chain method developed at Google. It would be seen as very relevant, obviously, because Google is a very big name. However, the success of Google has nothing to do with supply chain. Google has been a fantastically successful company, but its success does not originate from its supply chain practices. If we were to look at such a case study, it would carry a lot of weight, and I would say a lot of undue weight, just due to the brand name that Google carries. Just because Google has hired many super talented engineers and has redefined the state of the art of software engineering in many areas, there is no reason to believe that it would automatically transfer to everything they do, especially if it’s something that is a support function for them, like supply chain.

That is interesting because if I go back to Claude Bernard’s book, “An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine,” the first thing that Claude Bernard presents is the rejection of authority as an integral part of the scientific method. In the mid-20th century, he said the biggest problem with the medicine of the time was that it was mostly a matter of authority. People believed something to be true just because there was a big name or someone who carried a lot of weight in society supporting the theory. This is wrong. The radical position of Claude Bernard is that, as far as science is concerned, we need to reject all authorities except those directly obtained through experiments. The ultimate source of authority, and actually the only source of authority in terms of scientific truth, should be the experiment or, in other words, reality itself.

When we start looking at case studies, we have authority problems all over the place. To emphasize this point, I’m listing four remarkable companies. All of these companies are widely recognized, highly successful, and have faced absolutely epic supply chain failures in their history. These failures were due to an insane combination of arrogance, greed, sloth, ignorance, and various other problems. To give you a few examples, Nike, in 2004, lost $400 million in a misguided attempt to improve their supply chain with a software vendor. Lidl, in 2018, lost €500 million with another big-name supply chain vendor. I believe these numbers are only a small fraction of the actual cost to these companies, as the monetary loss was just one aspect of these epic-scale failures. The management was distracted for years, and in Lidl’s case, almost a decade. The opportunity cost of these failures is absolutely gigantic.

I’m not saying that these companies aren’t doing certain things very right. They are truly remarkable and have survived epic-scale failures in their supply chain, which proves that they were doing things in ways that were very remarkable; otherwise, they would have gone bankrupt. However, the point I want to emphasize is that it’s not because a company has a good name, good reputation, and is fantastically successful that we can infer anything about the quality of its supply chain practices. This is my key criticism, and just like Claude Bernard was saying, we have to fundamentally reject all those mechanisms that rely on authority. We have to do that also in the field of supply chain studies.

However, we have another set of problems, and it’s a taboo. If I look at published case studies, just as a gut feeling without actual statistics, I would say 99% of the case studies are positive. They show a problem, a legacy solution, a new solution, and the new solution brings a positive outcome. Yet, I’ve been discussing with supply chain directors for over a decade, over 100 of them, and my perception is that the vast majority of supply chain initiatives fail. Usually, the failures are not as epic as the ones I previously mentioned, but they are all over the place, and the vast majority of those initiatives fail. It’s not overly surprising—if one company managed to systematically and without fail improve its supply chain and applied this method over and over for a decade, this company would be crushing the competition, similar to Amazon’s story. But I digress.

Back to the idea of taboos, I believe we have a manifest disconnect between the overwhelming positivity of case studies and the overwhelming negativity of the actual real-world supply chain experiences. This can be simply explained by the fact that failure, to a large extent, is a taboo. There is a fantastic article called “The Last Days of Target” by Joe Castaldo, published in 2016, about Target Canada. Target, a North American retail chain, tried to enter Canada, invested over $5 billion in this undertaking, and everything went to complete disaster. They ceased operations with massive losses, and at the core of the problem was a long series of brutal supply chain issues. In essence, it was a long series of massive supply chain mistakes.

The funny thing is that Joe Castaldo does a fantastic job describing the problem from a journalistic perspective. It doesn’t put anybody in a good light. The story shows a wild combination of arrogance, pride, stupidity, ignorance, and wishful thinking. You can see highly-paid executives making a long series of absolutely stupid decisions, encouraged by a vendor that doesn’t have the slightest clue about what they’re doing in terms of supply chain analytics. Everything blows up in a rather spectacular fashion. It takes such a degree of courage to publish such a story. I don’t know Joe Castaldo personally, but I would be terrified by the idea of publishing such a story, because the lawyers of Target and the software vendor, whose name I cannot even pronounce, would likely sue anyone telling this tale because it’s so dismal. We have a problem—there are many things that literally cannot be told due to taboos. I believe this explains the massive bias in case studies, which tend to only reflect the good outcomes, resulting in a significant survivorship bias. Is this a new issue? Absolutely not.

If we look back at the book by Claude Bernard, a renowned scientist, he became famous by making extensive use of vivisection, the dissection of live animals. In his book, he states that the method is vile, cruel, brutal, and gross, but he also argues that it’s essential for modern medicine. Not only was he proven right in his time with his discoveries, but a century and a half later, there is no doubt that vivisections were fundamental to the establishment of the progress we enjoy in modern medicine today.

Science is not about what makes us feel good or comfortable. Often, good science looks at the things that make us most uncomfortable. Intuitively, this can be understood because we’re not afraid to look at the areas where we are comfortable. Our intuition is probably going to be fairly good in those areas. However, the areas that feel wrong, where we have an instinct of repulsion, are precisely where we’re not going to instinctively look. That’s why we need something like the scientific method to help us have a more careful, impartial look at reality that is not completely polluted by biases.

To conclude on taboos, case studies often take the problem from the wrong end. They go along with the propensity to see positive results and eliminate the bad ones. But this is not even the end of the story.

Could we have good reason to think that the people involved in case studies have a propensity to exaggerate the results? My proposition is yes, absolutely. It’s not hard to see why.

If you are an executive and participate in a case study that claims you managed to achieve a stunning success, saving millions of dollars for the company, it looks very good on your resume. It will improve your prospects of getting a bigger position either internally in the same company or externally in another company. Everybody who has worked in a large company knows that it’s not only about doing things of great service to the company. If you want to advance in a large company, you not only need to perform great service for the company, but also make people aware of your achievements. There’s a massive conflict of interest for those involved in case studies, as they are the ones who come up with the numbers that justify the profits. It’s rare that you can derive the profit generated by a novel method, technology, or process just by looking at the accounting books. Usually, it’s much more indirect; you need to reprocess the numbers, frame the benefits in a way that makes sense, and make plenty of assumptions. This can be fairly subjective, and when people have a significant conflict of interest, we know for sure that it’s going to distort the results. This conflict of interest can lead to exaggerating the positive outcomes.

To address this issue, some may involve a neutral third party to provide an objective opinion and ensure everything is done fairly. There are two primary types of neutral third parties: market research firms and academic researchers. However, I believe these parties are not neutral at all.

Market research firms are in the business of surveying the market, assessing the relative strengths and weaknesses of solutions, and selling the results of their research as reports to companies seeking solutions. These companies can buy the report and have an impartial view of the market provided by experts, allowing them to pick the best vendor. In reality, the big market research firms I know of don’t make their money from selling reports; the bulk of their revenue comes from consulting and coaching services that they sell to solution vendors. This puts these firms in a position where they want to do what’s best for their clients, who are not the companies seeking solutions, but rather the tech vendors who are paying for consulting services.

It turns out that this supposedly neutral third party is actually heavily conflicted and can make the problem worse by adding their own layer of bias on top of the existing biases. When looking at academic researchers, they have plenty of conflicting interests of their own. Publish or perish is very real in the academic world, and negative case studies, especially the sort you would likely encounter in supply chain, are not the epic scale disasters but rather small-scale, disappointing failures. It’s very much in the interest of an academic researcher to show positive results because they are easier to publish.

Some may argue that publishing fraudulent results could ruin an academic researcher’s career, but when it comes to case studies in supply chain, researchers can rest assured that nobody is going to debunk their results. It’s exceedingly difficult to conduct experiments in supply chain, and it’s even more difficult to debunk anything that happened to be false and published. It would be nearly impossible to prove that a case study from the past was wrong or that the results were grossly magnified. This isn’t to say that researchers are dishonest, but they do have a clear conflict of interest, and it’s impossible for an observer to differentiate the honest researchers from the dishonest ones. As a rule of thumb, when a third party is involved in a case study, it’s usually even more biased than if no third party was involved, which is quite surprising.

Now, to conclude this series on case studies, let’s have a close look at the vendors. People often believe that vendors are not supposed to lie, but this is not entirely accurate. There is a notion known as the “dolus bonus,” or “good lie,” introduced by the Romans a long time ago.

To understand this concept, consider a merchant at a market selling eggs and making an outlandish claim that an egg is the best one you will ever eat and that it will make you happy for an entire month. Obviously, the claim has absolutely zero chance of being true. The Romans asked the question, should we do something about this lying merchant? Should we put this merchant in jail or fine them? The answer was no; it’s absolutely fine. This “dolus bonus” concept suggests that if you’re a merchant, it’s just part of your nature to lie about what you’re selling. While there are limits, the law recognizes that vendors will do what they do, and you should not blame them for trying to put their products in a favorable light, even absurdly so. That’s just how the market works.

Even if vendors are not aware of the legal fine print, they intuitively know this, and thus there is a propensity to produce case studies that cost money and time, essentially serving as sophisticated infomercials. While advertising serves a function in society, the belief that glorified advertising can be a vehicle for conveying knowledge is misguided. By design, case studies cannot be salvaged for this purpose.

So, if we eliminate case studies as they are completely invalid, what are we left with? We need to find an alternative method that does not suffer from the same problems. This is where supply chain narratives come in. The intent of a supply chain narrative is to describe problems so that knowledge can be shared among supply chain practitioners and researchers, focusing on the issues at stake and what we are trying to solve.

To get started, let’s discuss a very interesting book, a novel called “The Phoenix Project.” While it may not be a landmark of science, it is an enjoyable read about a fictitious company, told through the eyes of the IT director. Most events in the story involve a series of supply chain and enterprise software problems that are deeply entangled. The story tells of the struggles the company faces and what people do to solve those problems. What’s surprising is that this work of complete fiction resonates profoundly with many who read it, even more so than most case studies, except for perhaps the negative ones like those produced by Joe Castello.

This apparent paradox may not be a paradox at all if we consider the first step taken by the authors. They decided that the story would be about a fictitious company, which removed all the problems attached to the name and the authority that comes with a case study tied to a well-identified company. By creating a work of fiction, they eliminated the allure of authority that would be attached to a real company.

Secondly, in terms of taboo, the fictitious company allowed the authors to explore many interesting aspects of the story. Most of the characters have limits, they are flawed, they struggle, sometimes they make dumb mistakes, and sometimes they are self-serving to a point that really harms the company. They can be very greedy in ways that are completely at odds with the company’s interests. You can see how certain characters lie to their colleagues. In a case study, it would be impossible to write this story because it would lead to a long series of litigation if done with real people.

However, could we say that this novel is a scientific piece of work? No, and for a simple reason: the novel is an advocacy for DevOps, a philosophy to approach the development and maintenance of enterprise software. The authors tell the tale of a set of characters in their fictitious company facing immense struggle and gradually overcoming the challenges they face until they have rediscovered the core principles of the DevOps philosophy. This book comes with a very loaded agenda, and the authors are not making any secret about it; they are pushing for the DevOps agenda.

My primary criticism is that we have the same problem that we have with case studies: a complete conflict of interest. The authors happen to be consultants who are selling consulting services to help implement DevOps practices in companies. The fact that in the story, everything can be solved in credible ways and that there is a happy ending where the company ends up making massive profits thanks to this methodology is far from being objective.

The idea of a supply chain narrative is that we want to start with a fictitious company but have an exclusive focus on the problems. We want to address the problem by creating a fictitious company so that we don’t have the authority problem and the taboos. However, we don’t want to include the description of the solutions in our narrative, as this would lead to a long series of conflicts of interest. We want to focus exclusively on the problem side of things and push aside the solution side.

There may be some modest exceptions to this rule because sometimes, to justify that a given problem is relevant, you need to provide an intuition of the solution. If you don’t give the intuition of the solution, the problem seems outright impossible. To avoid objections that some challenges are impossible to address and therefore not interesting, we may need to introduce a tidbit of a hint concerning the existence of at least one solution. We don’t claim that it’s a good solution, just that a solution exists.

The goal of the supply chain narrative is to inject reality and real-world experience into the field of supply chain management. We want this format to be a proper vehicle to convey knowledge to fellow supply chain practitioners and researchers, and even help us reason about the supply chains ourselves, which is quite a big challenge due to their complexity. To make the whole thing intelligible and credible, we need to have a backstory and context. We want to magnify the relevance of the problems presented in the narrative.

However, if we come up with a fictitious company and list all the problems that impact supply chains, can we just call it science? Absolutely not.

The problem is that we need to make it very easy to reject the validity of a narrative. In a case study, it’s very easy to come up with one, but it’s incredibly hard to debunk or reject its validity. With the design of the narrative as a method, we want to reverse this problem. We want to create something that is exceedingly hard to craft but relatively straightforward to reject.

The first criterion would be resonance. If we have a narrative about a specific company archetype in a specific industry and we talk to supply chain directors of that industry, would they agree that this narrative resonates with the sorts of problems they have? Although it may seem very subjective, I don’t believe it’s that subjective. If we look at the book “The Phoenix Project,” virtually every single person among my colleagues who has read it found that it resonated with their experiences in various companies. We are not focusing on the solution, merely on the problem definition. Even if there can be widespread disagreement on what to do about the problem, there is usually strong agreement on the problems that are on the table. It’s not necessarily as subjective as it seems, although there is an irreducible degree of subjectivity.

Another factor is exhaustivity. If you can pick a company that would supposedly be a good match for this persona and show that this company has important problems that are not even listed in the persona, then the burden of rejection is very lightweight. You just have to exhibit one company, one problem, and say, “This is cause for rejection of the persona.” It doesn’t require months of work, just a bit of feedback and a good-faith description of an important problem.

A good persona should also take risks with regard to numbers, and by numbers, I don’t mean precise numbers, but orders of magnitude. We need to clarify whether we’re talking about a company that is trying to operate 100 SKUs or 100 million SKUs. We need to give the characteristic dimensions and orders of magnitude that characterize the company. If you find a company that doesn’t match the given orders of magnitude, it may mean that we have incorrectly framed the persona.

The last point is more subtle but also quite important: the existence of solutions in the market. Depending on the solution that exists or doesn’t exist in the market, that can be used to reject the validity of a persona. If we have a solution that completely trivializes the problem or offers a definitive solution so that what was previously a problem becomes a non-problem, then this is a cause to reject the persona, at least in its current form.

To give you a more concrete example, if we take a large company that operates with tens of thousands of SKUs in a warehouse in 1950, this company’s persona could list maintaining proper stock levels as a major challenge. At the time, stock levels had to be maintained manually through a small army of clerks who were updating registries. It was actually an immense challenge to maintain accurate inventory records over time. But fast forward 70 years later to the present time, could we still consider that a challenge? Not at all. With barcodes and inventory management software, maintaining accurate stock levels in a warehouse is essentially a completely solved problem. It’s not worthy of inclusion in a persona because there are plenty of solutions, and there is virtually zero uncertainty about the type of solution needed.

I am presenting a duality of problem versus solution, and the reality is that it can be surprisingly difficult to have a clean separation between problems and solutions. It’s challenging to think about a problem if you can’t imagine a solution first and vice versa. One source of difficulty in understanding problems is the latent ideology that permeates society. We have values that are simply a part of our society, and we live with them without even perceiving them. These values can have a massive influence on the way we look at problems and whether we decide they are relevant or not.

To illustrate this, I would like to bring forward the case of randomness. Randomness has been associated with the stigma of gambling, which was perceived as wrong. In Claude Bernard’s “Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine,” Bernard is vehemently against the presence of randomness in the field of science. He says that if an experiment is not perfectly deterministic, it’s usually a strong sign of bad science or, at best, incomplete science.

Fast forward 70 years, and we see Albert Einsteinmade massive contributions to the field of quantum mechanics, and he was very conflicted about some aspects of it, particularly the indeterminism or randomness that seemed to be a fundamental property of the universe. Einstein, on multiple occasions, acknowledged that quantum physics was probably not wrong because its operating properties were excellent. However, he felt that the non-determinism suggested that quantum physics was incomplete and not the final product of what physics should be. It took many decades, but nowadays, the perception is that indeterminism is truly a fundamental property of the universe, and there is no escape.

My pet theory is that the stigma of gambling, which was associated with randomness, persisted through the ages and even influenced the present. A decade ago at Lokad, we decided to push the idea of probabilistic forecasting, embracing randomness instead of rejecting it. This led us to completely redefine the problem, and we were met with skepticism and even more visceral reactions. Some questioned the relevance of randomness to the problems they needed to solve.

From my perspective, studying the structure of randomness itself is of high interest. However, we may have preconceived ideas that hinder our understanding of certain issues. Another challenge is the distraction that can arise when an excellent solution emerges for a difficult problem. It can become difficult to think about the abstract problem, as we tend to define it reflexively with regard to the solution.

A historical example of this is the development of flying machines in the 19th century. Lighter-than-air flying machines like hot air balloons were discovered and used to make stunning discoveries. The success of these lighter-than-air machines distracted the relevant communities from considering heavier-than-air alternatives. It took decades for the relevant communities to explore alternatives, and I believe that part of the problem was that having a stunning solution, like building a flying machine, was massively distracting.

Another challenge we face when examining problems and situations is when the problem is unthinkable. It’s the sort of thing where you can’t even conceptualize the problem, despite it being a real issue.

To illustrate this idea, I would like to refer to a fantastic paper published in 2018 by a research team at Facebook on machine translation. Machine translation involves taking text in one language and using a machine to produce a translation in another language. This field of study has existed for about 70 years. The first automated translators were incredibly naive, simply using dictionaries to replace words from one language with corresponding words in another. This approach resulted in very low-quality translations.

Over the years, techniques evolved, and most methods had one thing in common: the use of bilingual corpora. The idea was to use datasets containing phrases in two languages, learning from these examples to build an automated translation system. The stunning result achieved by the Facebook research team was the development of a translation system without any explicit translation dataset. They used a vast dataset of text in French and a separate, disjoint dataset of text in English, and then built a machine translation system that could translate from French to English without ever being given any examples. This result goes against the conventional approach to automated translation and required an actual solution before people could even rethink how they should approach the problem.

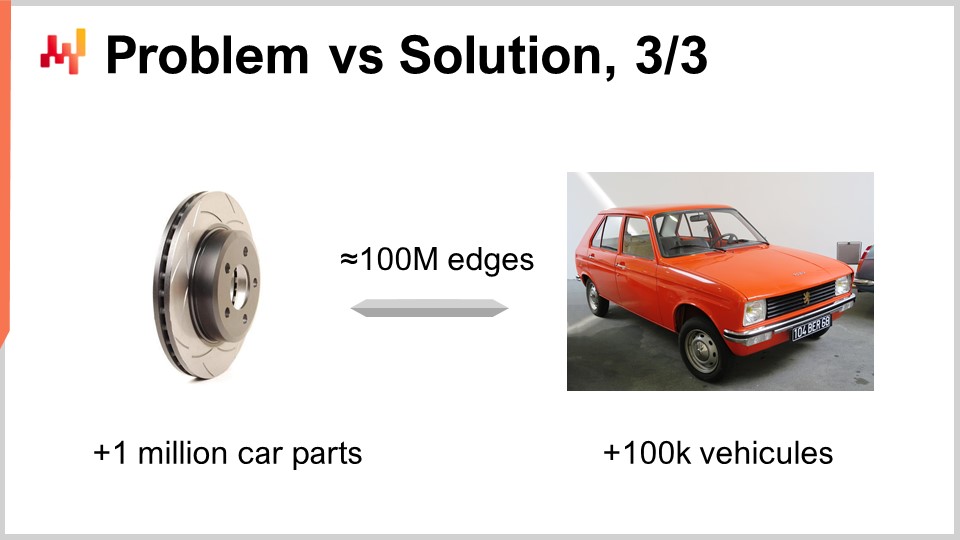

A more modest but relevant example from our work at Lokad is in the automotive aftermarket. In this field, the challenge is finding the right car part with the correct mechanical compatibility for a specific vehicle. In the European market, for example, there are over 1 million distinct car parts and over 100,000 distinct vehicles. When you go to a garage and need a part replaced, the person at the shop must consult some kind of service to determine which part is suitable for your vehicle. It turns out that the entire list of part-vehicle compatibilities, which I refer to as the edges that connect parts and vehicles, has an order of magnitude of about 100 million compatibilities. In this market, there are a few heavily specialized companies that maintain this dataset for the European market. They sell access to this dataset to virtually every single company that operates in the automotive aftermarket industry, one way or another.

The problem is that this dataset is enormous, with 100 million compatibilities, and it has plenty of mistakes. Based on various sources, I estimate that there are a few datasets for Europe, and most of them have about a 3% error rate. The errors are both false positives, where a compatibility is declared that doesn’t exist, and false negatives, where a compatibility exists but isn’t properly recorded in the system. These errors create ongoing problems for all the companies operating in the aftermarket.

When a repair needs to be performed, and a client is in a hurry, the vehicle isn’t moving anymore. They order a part, the part arrives in time, but then people realize the part isn’t compatible. The part has to go back, another part is ordered, and extra days of delays and client frustrations occur. So, it is a problem, but what can we do about it? The companies maintaining these datasets manually already employ small armies of clerks to keep them up-to-date. They are fixing mistakes all the time, but they also add new parts and new vehicles constantly. Over decades, the dataset slightly grows, errors are fixed, new errors are introduced, and the 3% error rate remains somewhat constant. It does not improve over time.

The system has already reached an equilibrium, and companies in the automotive aftermarket space may not be willing to pay ten times more for the companies maintaining the datasets to hire ten times more clerks to correct the remaining errors. There are diminishing returns, and the errors that haven’t been detected yet are probably very difficult to fix.

At Lokad, we developed an algorithm that detects both false positives and false negatives and can automatically fix about 90% of these problems. The beauty of it is that this algorithm uses nothing but the initial dataset. It might seem odd, but we can use this very dataset to learn the mistakes within the dataset, and that’s precisely what we did. By the way, I will be presenting these techniques in detail in a later lecture. You can check out the plan online; the schedule for the lectures is available on the Lokad website. So, this is another example where, until you have a solution, it’s very hard to think that there is even a problem in the first place.

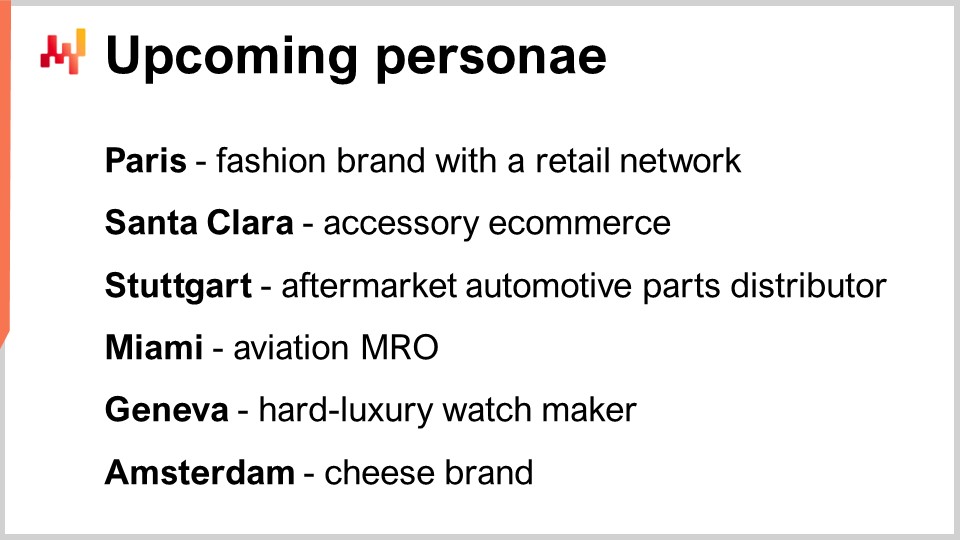

As part of my intent, I will be presenting a short series of lectures on personas that characterize archetypes we have encountered at Lokad. I will do my best to summarize the way I see the problem, synthesizing all the experiences I have accumulated through my own experience and through the experience of my colleagues at Lokad. Again, you can check that I will not be presenting all these personas in sequence because that would be probably super tedious for the audience and maybe a bit tedious for me as well. So, I intend to present one persona probably two weeks from now and then I will jump to other elements of interest.

In conclusion today, we have raised some very important questions about supply chain as a field of study, and I hope that I have been able to present some very promising answers, maybe not proven ones, but at least provide some promising answers to these questions. I also realize that probably among the circles of people who have spent a good portion of their professional life producing case studies, I probably didn’t make any friends today, and I really hope not to end up like the guy in the illustration. That would be pretty terrible, but again, I think the stakes are pretty high. We want to establish and elevate the supply chain as a field of study to a science, so that we have something that is very capitalistic, aggressive, and where we can expect to have reasonable expectations to deliver improvements in reliable and controlled ways.

So, this is it for today. I will be looking at the questions now.

Question: I did not understand the concept of exhaustivity for the personas. Can you elaborate?

Okay, exhaustivity is just that, due to system effects, the description of the supply chain challenges and problems should be complete. Supply chains involve a long series of trade-offs, so if you omit one of the forces at play, you may not be reasoning correctly about the problem in the first place. For example, you cannot reason correctly about what is the optimal stock level if you ignore the problem of having a limited supply of working capital. Exhaustivity means listing all the things that are very relevant, and if we are not exhaustive in listing all the relevant problems, it probably means that this is not a very good persona, as some things may have been overlooked and that might critically endanger any reasoning based on this persona.

Question: The wrong type of solutions in supply chains are prevalent, and there are a lot of supply chain practitioners who know that they are broken by design. How can we help them give up and switch to approximately correct types of solutions and embrace uncertainty?

First, I think the main problem is that supply chain as a field of study is still in its pre-scientific infancy, and there is widespread skepticism about the validity of pretty much everything that is published. It’s very hard to convince people. I think the first step is to convince people that supply chain is eligible for the scientific method. This would be a significant first step because it’s not a matter of opinion or ideology; there is potentially an endgame where we have objectivity and knowledge with good qualities. We can have solid foundations for understanding the problems and applying proper solutions. The first step, and that’s what I’m trying to do through these lectures, is to educate the public at large that supply chain is not just a practice or an art, but it could be a science.

Claude Bernard, considered one of the fathers of modern medicine, faced many objections in his time. He was confronted by doctors who claimed they already had the science and that there was nothing to be learned from his methods. They suggested he should just stick to their theories and not conduct his experiments. The biggest battle that Bernard had to fight was the very idea that medicine was eligible to be studied with a scientific method. Similarly, I suspect that most of what is published, even among academic circles, about supply chain is not scientific. I believe I have demonstrated today that a good portion of the literature, such as case studies, is non-scientific. In the next lecture, we’ll see what has to be done with the other half of the literature that remains, and it’s not very promising.

When it comes to your question about uncertainty, my first step would be to convince people that uncertainty is irreducible and that they will have to deal with it as a massive problem in their everyday lives. Can we agree that there is zero hope that we can perfectly anticipate what people are about to buy? To perfectly anticipate a person’s actions in a store, you would need to perfectly replicate their entire intelligence. The algorithm that could predict every single move of a person would fundamentally be as smart as a perfect replication of human intelligence, which seems highly unreasonable. The alternative proposition that uncertainty is irreducible to a large degree feels like a much more reasonable proposition. The biggest challenge is to bring the discussion to a place where we are reasoning from a semi-scientific perspective instead of relying on practices, gut feelings, intuition, and authoritative statements.

Question: What are your thoughts on design thinking?

I’m not too sure about the specific question here, but what I’m trying to bring is a connection between supply chain and the real world. If we can have supply chain experiments that align with what is done in many other experimental sciences, we can connect supply chain with the real world in a satisfying way. I have presented one method today, the persona, and there are probably plenty of other methods. I’m not following any specific way of thinking; I’m more interested in the method to produce knowledge rather than the way people think.

In this regard, I’m very much aligned with the sort of ideas that Claude Bernard presents. The initial spark for knowledge, the emotion, the intuition, is fundamentally something that is not scientific at all. It lies in the realm of emotion, not reason. I don’t think you can truly rationalize this part, and even if you could, I would be very suspicious that the same method would work for everybody. But I digress.

I think we are done with the questions for now. See you next time in two weeks; we will meet on the same day and time. We will explore a persona named Paris for a fast fashion company operating a retail network. See you then.

References

- An introduction to the study of Experimental Medicine, Claude Bernard, 1865

- The Phoenix Project: A Novel about IT, DevOps, and Helping Your Business Win, Gene Kim, Kevin Behr, George Spafford, 2013

- Unsupervised Machine Translation Using Monolingual Corpora Only, Guillaume Lample, Alexis Conneau, Ludovic Denoyer, Marc’Aurelio Ranzato, 2018