00:17 Introduction

06:07 The story so far

07:31 The short definition (recap)

08:38 Crafting a supply chain persona (recap)

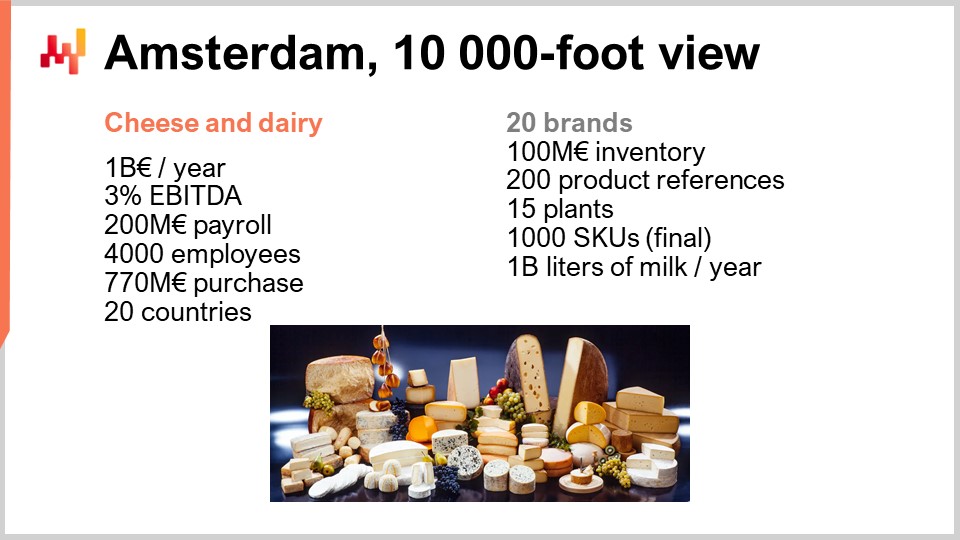

10:29 Amsterdam, 10 000-foot view

13:28 On the menu

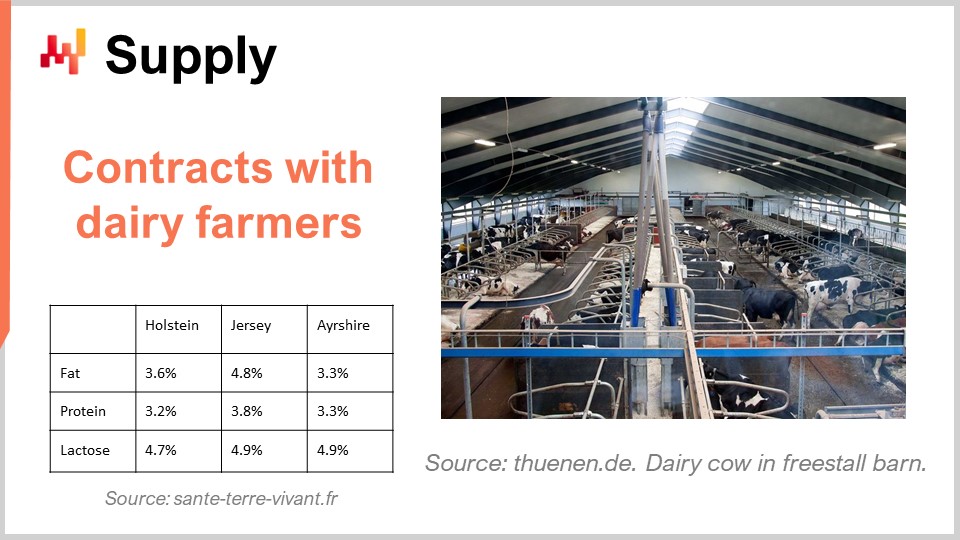

14:16 Supply

18:38 Network

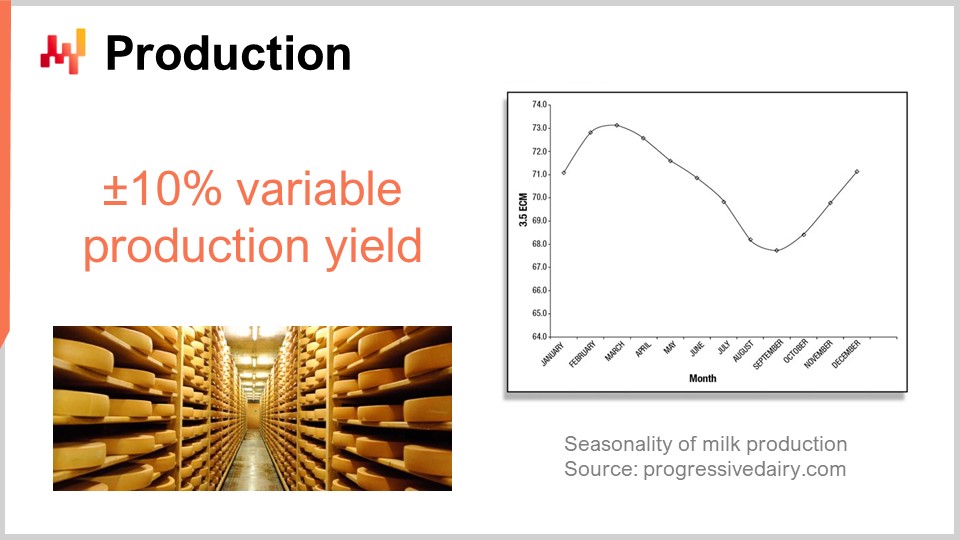

21:36 Production

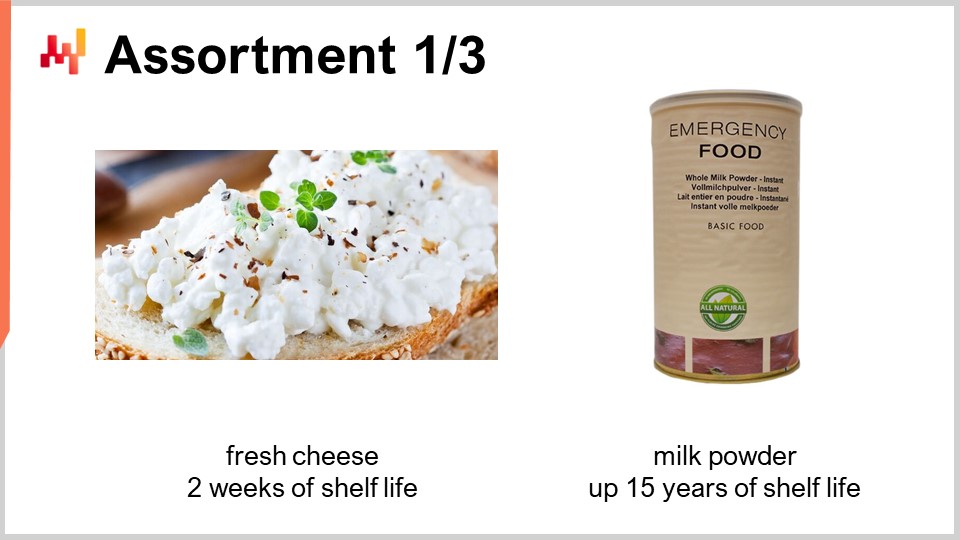

25:28 Assortment 1/3

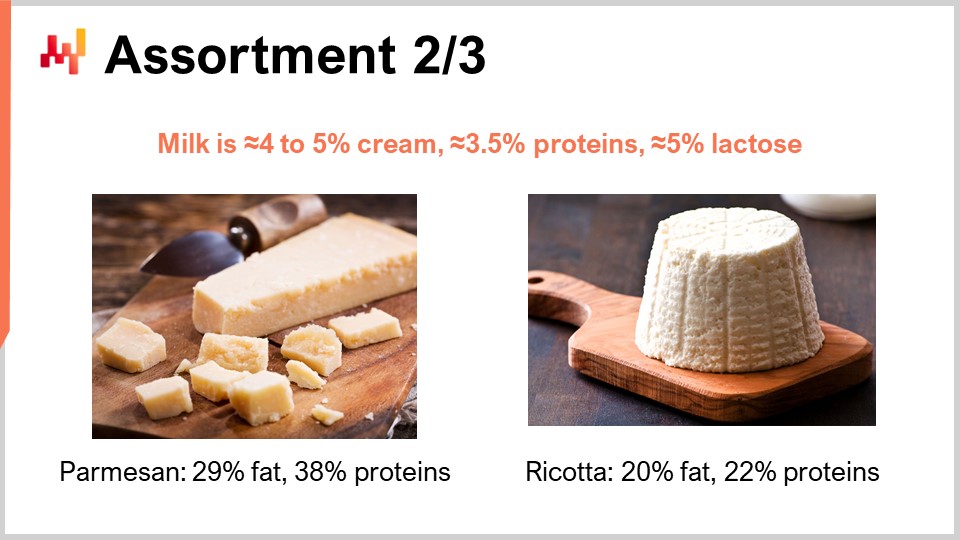

28:11 Assortment 2/3

30:11 Assortment 3/3

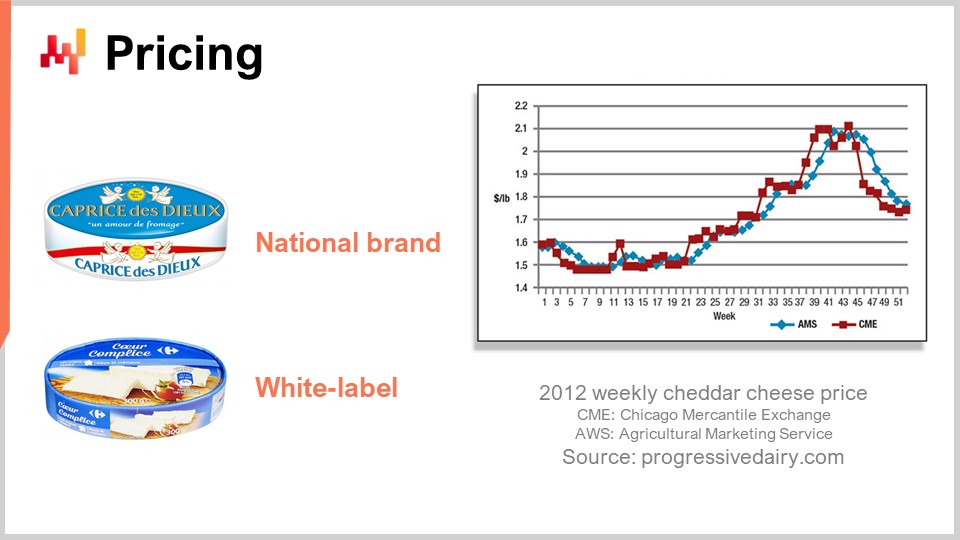

33:38 Pricing

38:37 Channels

44:18 Promotions

52:38 Copacking

55:08 Conclusion

57:43 Upcoming lecture and audience questions

Description

Amsterdam is a fictitious FMCG company that specializes in the production of cheeses, creams and butters. They operate a large portfolio of brands over multiple countries. Many business conflicting goals must be carefully balanced: quality, price, freshness, waste, diversity, locality, etc. By design, milk production and retail promotions put the company between the hammer and the anvil in terms of supply and demand.

Full transcript

Welcome to this series of supply chain lectures. I’m Joannes Vermorel, and today I will be presenting Amsterdam, a supply chain scenario. Amsterdam is a fictitious company. In this case, it is an FMCG (Fast Moving Consumer Goods) company that produces and sells a series of cheese brands. In this lecture, we will be reviewing the supply chain problems and challenges faced by Amsterdam. Cheese was invented about 10,000 years ago; however, as we will see, there is nothing really simple or ancient about cheese supply chains.

This lecture is not just intended for cheese and dairy specialists. On the contrary, it is intended for a wide audience of supply chain practitioners. This lecture is illustrative of the sort of problems that emerge in real-world supply chains, as opposed to the sort of toy problems that emerge from supply chain textbooks. The goal of this lecture is to assess the applicability of candidate supply chain solutions. Indeed, the applicability very much depends on the problem at hand, and if we don’t properly characterize the problem that we try to solve, the odds that a solution of interest may turn into something profitable and generate tangible, measurable results are approximately zero.

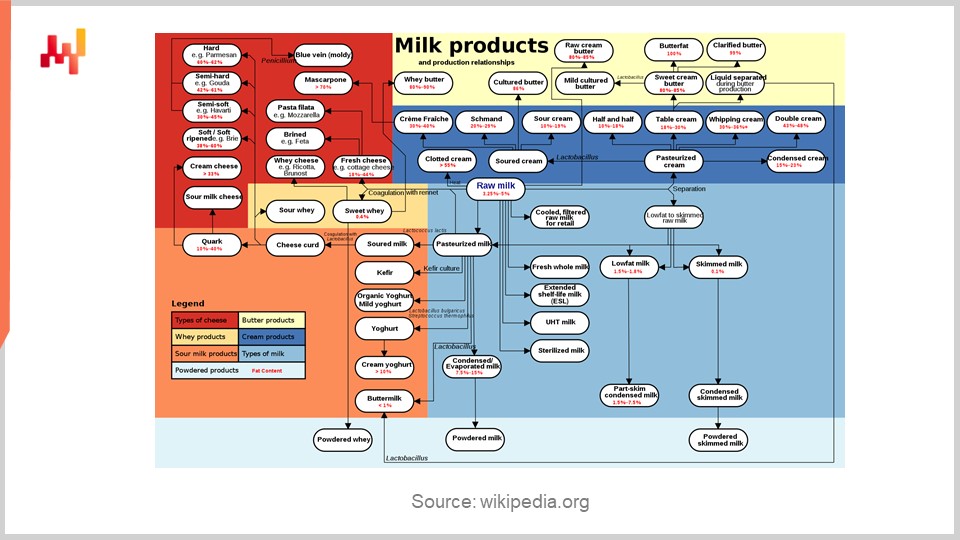

The production and supply chain of cheese are very much dependent on the chemistry of milk. Cow milk is approximately 88% water, 4.5% lactose, 3.5% fat, 3.5% protein, and 0.5% minerals, also called ash in the case of milk. Worldwide, the production of cow milk is about 25 times larger than the production of goat milk. When you process milk, you don’t get to choose what you’re going to do with it. There are very established processing pathways, as shown on the screen. This is a very complex chemical diagram, but fundamentally, it is illustrative of the fact that the pathways have been chosen for you.

From the perspective of Amsterdam, which operates in this space, these processing pathways are the base reality. Those processing pathways are the base reality of Amsterdam’s supply chain as well. Thus, the question is: when we start considering a supply chain solution of any kind that is supposed to deliver some kind of intended improvements, we need to ask ourselves if this solution is even relevant for the problem at hand. Does it embrace this base reality or does it just pretend that this base reality doesn’t even exist?

For example, many experts frame inventory policies as push or pull. But is it really making sense in this case? I believe that this duality is mostly irrelevant in the case of Amsterdam. Indeed, milk comes from cows, and Amsterdam doesn’t get to choose whether cows produce milk or not. Cows are going to produce milk, and so, in the short term, Amsterdam has almost no control over the production of milk. The supply side of the equation is pretty much rigid.

On the demand side, the demand comes from retail chains that pass orders to Amsterdam. But in the short term, Amsterdam has very little leverage in this area. The demand is mostly what it is. Thus, we can see that Amsterdam has a supply chain that is stuck between the hammer of demand and the anvil of supply.

What is very interesting is that the art of the practice of supply chain management at Amsterdam consists of profitably mitigating all the problems that emerge from the fact that the supply chain, by design, is between the hammer of demand and the anvil of supply. That’s where the crux of the supply chain practice lies for Amsterdam. This is really the sort of practice that we need to capture and improve.

This lecture is part of a series of lectures. In the first chapter, I described my views on supply chain both as a field of study and as a practice. What we have seen is that supply chain is fundamentally a collection of wicked problems, as opposed to tame problems. Tame problems do not lend themselves to naive approaches; they are defeated by naive approaches or methodologies. That’s why the entire second chapter is devoted to methodologies that are appropriate both to study supply chains and to improve them.

The very first lecture I gave in this second chapter was about supply chain personas. Today, this is the first supply chain persona that we introduce in this series of lectures. The first one was Paris, a fashion brand; the second one was Miami, an aviation emirate; and today, we have Amsterdam, a cheese brand, or a series of cheese brands more precisely.

A brief recap on what supply chain actually is: I define supply chain as the mastery of optionality in the presence of variability when managing the flow of physical goods. This is very distinct from logistics operations. This is not to say that logistics operations are not important; they are both absolutely critical for the success of the company. However, what I’m saying is that supply chain, as I position it, is essentially a science of the decision-making processes that exist in the company. This is fundamentally a discipline that focuses on cultivating options and then being able to pinpoint the right options among all the available options and turn those options into actual decisions.

Now, supply chain personas: a supply chain persona is a fictitious company. This concept was introduced in the very first lecture of my second chapter, and it comes with an exclusive focus on the supply chain problems, as opposed to having an entanglement of problems and solutions. Indeed, when we start looking at solutions or case studies, we end up with a problem of having deep conflicts of interest. The people who are pushing a solution forward have an agenda of their own. They become vendors in a way, and this creates all sorts of problems where it becomes very difficult to assess, from a neutral perspective, the merits of the solution.

One element that I propose is to really entirely decouple the analysis of the problem from the analysis of potential solutions, which will be done later. We really need to keep the two completely isolated. Fundamentally, a persona is a tool to assess the relevance of supply chain solutions. It doesn’t qualify whether a solution is going to be good or not; it’s just a tool so that we can at least eliminate solutions where there is literally no hope of having something that even works because it’s not even answering the right question. This is a key insight: it’s better to be approximately right rather than exactly wrong.

Now back to Amsterdam. Amsterdam is a fictitious company, and it is essentially a large multinational FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) company. Its business is relatively straightforward: Amsterdam buys milk from dairy farmers, processes this milk into products, and then sells these products to large retail clients that typically operate large retail chains. That’s the essence of the business model of Amsterdam.

One of the key elements is that margins are thin, as illustrated by a 3% EBITDA. I give you a few seconds to read all those numbers that characterize this fictitious company. What we can see is that the margin is thin compared to a fairly large infrastructure of 15 plants. There is a large footprint in terms of infrastructure, and milk is basically the biggest element of the spend budget on what is actually purchased by the company. What we can see is that this margin at 3% is particularly thin compared to the size of the inventory, which is characterized as roughly 100 million euros in this example. Keep in mind that we are talking about essentially fresh products, so the amount of inventory is quite large, especially considering that most of this inventory is associated with products that have a limited shelf life. There is always a risk for this inventory of incurring severe depreciation if Amsterdam doesn’t succeed in actually selling the products soon enough.

However, as we will see, Amsterdam is not holding 100 million euros worth of inventory because they are inefficient; it’s just the sort of inventory that is needed first because clients expect a very high quality of service. There is also the manufacturing process of cheese, where typically many cheeses require some ripening period, which forces Amsterdam to keep some extra stock. Some cheeses take months to reach their full maturation, and that is reflected in the inventory held by Amsterdam.

On the menu today, we have a whole series of supply chain challenges, and that’s a summary of all the supply chain challenges faced by Amsterdam. The lecture will start with the supply side and progress toward the demand side of the supply chain of Amsterdam. Although this progression is mostly a matter of exposition for the sake of clarity of this lecture, in practice, all these problems happen simultaneously at all times for Amsterdam. There is no clear sequence; it’s happening all the time.

Let’s proceed then. On the supply side, securing a supply of fresh milk is absolutely critical for Amsterdam. Milk is the number one ingredient by far for every single product sold by Amsterdam. To secure this supply of milk, Amsterdam negotiates with dairy farmers. Typically, the supply of milk is secured via contracts that are negotiated possibly multiple years in advance. Indeed, in modern western dairy supply chains, the productive lifespan of dairy cows varies between two and a half and four years. Thus, essentially, if you decide that you will have a cow to produce milk, you’re stuck with this cow and the associated supply of milk for a very long period that spans over several years. This has implications in terms of decisions that Amsterdam needs to make on a daily basis. They need to ask themselves questions like: How many cows do we need to introduce into the supply network? What sort of contracts do we negotiate with the farmers? Where do we place those cows? Remember that the operations of Amsterdam span across extended geographies, so the placement of the cows is very important.

Additionally, we have to consider which breed of cows we want. On the screen, you can see a table characterizing the chemical composition of the milk produced by various breeds of cows. Keep in mind that cow milk is 88% water, so even if the differences expressed in percentage seem small, once you remove the water, which is almost 90% of what milk actually is, you will see that these differences are very significant. As we’ll see later on, it is of critical importance to have the right mix for the composition of your supply, and by composition, I mean literally the chemical composition of your supply.

This is not the only complexity: the supply of milk is seasonal due to the metabolism of cows. Cows have a seasonality of their own as far as the supply of milk is concerned, and unfortunately, this seasonality is not magically aligned with the seasonality of the demand in the markets that are being served by Amsterdam. We will revisit this point in a few moments.

Amsterdam also needs to source other raw materials, such as herbs, food coloring, and packaging. However, all of those other elements put together are much smaller in terms of both financial importance and supply chain criticality than securing a supply of fresh milk. Not only are the financial stakes lower, but also the market is much less rigid. Amsterdam is definitely a massive player that absolutely needs to secure its supply of milk. In terms of packaging, for example, there is a vast market, and Amsterdam has much more short-term options on the table at all times for its supply of packaging. It doesn’t have to secure years in advance of packaging supply, for example.

There are many plants in the network of Amsterdam. Initially, we said that there were 15 plants. In terms of decisions, we have a whole range of long-term decisions about the network of Amsterdam, and more precisely, the placement of the processing plants and the placement of the dairy farms that will supply the milk to the plants. This is fundamentally a supply chain design problem. We have a trade-off: if Amsterdam has bigger plants, it can enjoy more economies of scale and lower its production cost. However, the fewer the plants and the more concentrated the production in a few areas, the greater the transport will be. Potentially, you will have to cross borders, and you can have all sorts of complications that arise when you have non-local production. So you have a trade-off between how big you want your plants and how many plants you want to have. This balance needs to be adjusted, looking years ahead. However, there are also short-term problems that are fundamentally vehicle routing problems, where you want to organize the daily collection of the milk. Here, you really want to optimize all your routes, where every single dairy farm is going to be collected every single day. You want to make sure that, network-wide, all the transport distances remain under something that is typically 70 kilometers. Keep in mind that there is seasonality at stake, both on the production side and on the demand side, which means that this network may have to evolve throughout the year to be adjusted depending on the season. Also, as Amsterdam is serving a very large collection of markets, this extensive multinational needs to gradually but continuously revisit its supply network and production network to gradually match and reflect the evolution of the markets themselves.

Indeed, if we go back to the fact that the margins are fairly thin, Amsterdam cannot afford to have ongoing excess capacity. This is just too expensive; the margins are too thin to be able to afford ongoing excess capacity.

Production-wise, every single day, for every single SKU, Amsterdam needs to decide how many units, that can be counted in grams, kilograms, or whatever, need to be produced. This is a decision that needs to be revisited literally every single day for every single SKU. We are talking predominantly fresh products.

Also, we have to take into account that Amsterdam needs to offer a very high quality of service to its clients. However, Amsterdam has almost no control over its supply, at least not in the short term. Fundamentally, we are facing a problem where all products are competing for the same supply, and remember the fine print of the milk composition: depending on what you want to produce, all products do not have the exact same requirements in terms of fat, proteins, and lactose. Every single day, Amsterdam needs to make all those production decisions. However, the problem is very severely constrained because, on one side, all products compete for the same supply, and also, it is not acceptable to have leftovers. Leftovers would be literally wasting some of the supply; if you don’t process your milk or if you don’t sell it very quickly, it spoils and goes to waste. This is not an acceptable solution, as the margins of Amsterdam are too thin for that.

On top of that, there is a production variability of plus or minus 10 percent. The production processes, such as the processing pathways that we have seen in the second slide of this lecture, are very complex. Most of those pathways are actually some kind of organic transformation, like fermentation. Thus, the production yield that you get is not something that is absolutely controlled. It is relatively controlled; however, observing an uncertainty in terms of production yield of plus or minus 10 percent is very frequent. Again, these are organic processes that are relatively controlled, but not absolutely controlled; this is not metallurgy.

It is possible to support the production for Amsterdam by sourcing or reselling a little bit of extra supply on the spot market for milk. However, Amsterdam is a very large company, and the spot market for fresh milk is shallow compared to the sheer scale of Amsterdam. We are talking about one billion euros of turnover, which amounts to around one billion liters of milk per year. At this scale, spot markets are very shallow, and it is absolutely critical for Amsterdam to have already secured its supply because the spot market will not be able to recover from a large imbalance between either a deficit or an excess of supply.

The assortment of products is key to solving the problem of facing the hammer of demand and the anvil of supply that I presented initially. Amsterdam’s supply chain is constrained between a hammer and an anvil, and the assortment of products can be leveraged extensively to regain options in this area. In particular, the first option is to leverage the varying shelf life of the products. Products range from fresh cheese, which has a shelf life of just a couple of days up to one or two weeks, to hard cheese, which has a shelf life of up to 10 months. The idea is that if Amsterdam faces not enough demand, instead of letting the surplus supply go to waste, it can temporarily produce more products with longer shelf life and store the extra supply. Later on, during the year, when seasonality on the demand side recovers, they will produce more fresh products and start depleting the stored long shelf life products.

Shelf life is not the only lever available. There is a small variant involving the duration of the cheese ripening process. To produce cheese, you have a process that involves organic transformations, and this process can last from a few days to a few months. Amsterdam can take advantage of this production delay, which is specific to the cheese and dairy industry, to mitigate short-term imbalances in terms of supply and demand.

Additionally, the supply of milk is not a one-dimensional problem. The composition of milk, meaning its chemical composition, matters very much. Some products have a completely different profile in terms of the ratio of cream, proteins, or lactose needed to produce them. Amsterdam needs to adjust its portfolio of products and brands so that the mix found inside the portfolio carefully mimics the mix on the supply side. This is a very powerful mechanism to adjust. If you’re thinking far ahead into the future, you can make decisions about adjusting the mix of cow breeds on the supply side to vary the mix, but you also have the opportunity to vary the mix found inside your offering. The goal is really to create a balance and alignment between supply and demand, taking into account the composition. It is also possible to have seasonal variations for the assortment. As we have seen, supply has seasonality, and demand also has seasonality; both need to be balanced. It is possible to regain some options and create alignment through seasonal adjustments of the assortment.

Cannibalization and substitution matter; products cannot be seen in isolation, and consumers have preferences but can also change their minds. Both cannibalization and substitution are constraints but also levers that can be used by Amsterdam. The idea is that if you’re facing a stockout on a given SKU, it is not necessarily as bad as it looks if you have products that are very close substitutes, for example, the same product in slightly different packaging. Conversely, if you have a product that spikes in demand, it is likely to cannibalize other products, so the impact on introducing an imbalance between supply and demand is not as great as it appears.

Pack size matters, and it is a matter of consumer experience. Consumers have preferences, and from their perspective, they would prefer a large variety of pack sizes, ranging from very small portions to family portions and extra-large portions for extended families or semi-professional needs, such as restaurants. There is a problem of choosing the granularity of variations in packaging, which is very much a supply chain problem. On one side, the consumer experience is improved if you have more variety. However, the more SKUs you introduce, the more supply chain costs you create for both Amsterdam and its retail clients. Due to cannibalization and substitution, if you have more SKUs, you take an extra risk of having leftover inventory for one SKU versus another. If you multiply the number of SKUs, you are not going to linearly increase demand; instead, most of the demand for a new SKU will come from cannibalization from neighboring SKUs. This ultimately increases the risk of inventory depreciation.

Another lever available for Amsterdam is pricing. In my perspective, pricing is very much a supply chain problem. Pricing has a profound influence on demand, and thus deciding what you want to produce or have in stock is fundamentally entangled with the question of what will be the retail price of the products that Amsterdam is trying to sell. All products compete for the same milk supply, so the decision to be taken by Amsterdam every day for every single product is whether the price should be moved up or down. Even if Amsterdam doesn’t change all its prices every day, this question can be asked and revisited daily. There is interest in doing this every day because it introduces small adjustments needed to keep supply and demand balanced, despite the rigidity on both sides.

However, the problem is that competitively priced products can cannibalize the supply of other, more profitable products. Pricing cannot be considered in isolation; if Amsterdam decides to lower the price point of a product, this product might see an increase in demand but can also cannibalize the supply that would be used for other products with better margins. This can only be considered at the assortment level.

Pricing also comes with some branding specificities. Amsterdam typically produces three kinds of products: national brands, which are owned by a company like Amsterdam and provide the best margins; white labels, which are similar products sold under the private label of the distributor; and hard discounts, where margins are lower but the quality of service and what is negotiated with the retail channel might also be lower. It is in Amsterdam’s interest to have a mix of national brands and white labels, as white labels ensure a guaranteed flow for their goods.

Hard discounts allow Amsterdam to place inferior production, reducing waste in production. For example, you may have cheese that is not as good because it has less cream, but it is considered inferior and fits the hard discount positioning. Amsterdam needs to maintain consistency across the board in terms of pricing for all these classes of products, from national brands, white labels, and hard discounts.

The key goal is for Amsterdam to maximize its overall profitability through pricing while minimizing inventory risk. Dairy product stock markets also exhibit seasonality, which is likely a consequence of the seasonality of production confronting the seasonality of demand. When supply does not match demand, the natural adjustment variable is price, which is reflected in public spot prices for dairy products.

Retail chains are the primary channel for Amsterdam, as this is where the bulk of its production is sold directly by providing products to large retail chains that have a mix of hypermarkets, supermarkets, and mini markets. This process is essentially pull-only, meaning Amsterdam has no short-term control over what is in the stores. Retail chains place orders, and Amsterdam has to comply and fulfill those orders. A very high quality of service is expected, with a service level above 98% being the typical benchmark for large fresh food FMCG companies. If Amsterdam doesn’t achieve these high service levels, they risk being delisted by the retail chains, so the stakes are very high.

To maintain this high quality of service, there is no workaround – inventories and buffers have to be maintained. However, when you have a combination of buffers and products with very short shelf lives, you have the perfect conditions for ongoing waste production. As Amsterdam operates on very thin margins, they cannot afford any non-trivial amount of waste. Reducing waste is not just a matter of sustainability, but also a matter of economic survival.

Amsterdam can leverage a secondary channel – food services, which includes canteens, schools, hospitals, and restaurants. This channel is highly tolerant of very short shelf lives. For example, if you deliver products to a hypermarket, they require products with a shelf life of one to two weeks to avoid waste and satisfy consumers. In contrast, food services are more accepting of products that expire within a day or two, as these products will be consumed almost immediately.

However, food services also expect much lower prices than what they would find at a hypermarket. If they could buy the same product at a similar price, they would just go to the hypermarket to purchase the products. Food services are of interest to Amsterdam because they can be a lever to use when products are nearing their expiration dates. However, food services overall are much more shallow and don’t have the same depth as retail chains, which means that if Amsterdam starts to purchase a large excess quantity, it’s going to exceed the capacity of this market to actually absorb what is being purchased. This will result in a massive price depreciation for Amsterdam. Thus, if Amsterdam can anticipate a week ahead of time that it’s about to face an excess of inventory for one product, it is better to start pushing ahead of time, a couple of days ahead, to the food services secondary channel to avoid being cornered later on with a very large excess that the secondary channel cannot absorb.

Promotions, in certain countries, represent about one-third of the sales volume for a company like Amsterdam. Promotions are frequently misunderstood in some supply chain circles as something that should be approached with time series forecasting and promotional forecasts. I believe that this view is misguided and even worse, mostly irrelevant to the sort of problems that companies like Amsterdam face.

Indeed, a promotion is first and foremost a negotiation that happens between Amsterdam and one of its VIP retail clients. The goal through this negotiation is to increase market shares. The retail chain wants to increase its own market shares against competing retail chains, and running promotions is a way to attract more clients to the stores. For Amsterdam, this is also about market shares – a promotion is a way to attract more consumers and gain market shares against competitors who operate competing cheese brands. The promotion is a negotiation and is supposed to be a win-win process for both the retailer and the producer.

Where time series forecasting is incorrect is that it’s not about forecasting an uplift of demand. The uplift of demand is engineered. There is a massive amount of self-prophetic effect – it’s because you target to double the sales and do all the actions required to make this happen that sales, in the end, double. This is not just a matter of being passive and expecting a forecasted uplift. From a supply chain perspective, this is not the right way to approach the problem – it’s about engineering a controlled uplift of demand.

There are at least three important “gotchas” when it comes to promotions. The first one is consumers and their opportunistic behavior. The goal for Amsterdam is to increase its own market share; however, what is most likely going to happen is that the promotion will cannibalize other brands. Amsterdam will observe an uplift of sales, but what is really of interest is the net uplift. This means considering the cannibalization that happens on products that are essentially similar to the one being promoted. The goal is not to increase the market share of one product but to increase the market share of the entire portfolio of products served by Amsterdam, and that is very tricky.

Also, consumers are intelligent, and if they see that Amsterdam, through its portfolio of brands, always has a couple of promotions, they will increasingly adopt opportunistic behavior. They will wait for promotions to happen before buying the product, adjusting their consumption patterns to steer their own consumption towards products most likely to be on promotion, and delaying their consumption when there are no interesting promotions going on, knowing that next week there will likely be one.

The second class of “gotchas” is that retailers themselves are shrewd and play the promotional game well. Time series forecasting of promotions is not the right perspective. If the retailer expects that, thanks to the promotional uplift, 100 units of a product will be sold during the promotional period of one week, it is in their interest to buy more than 100 units, maybe 150. The retailer is going to speculate on the stock. They will buy more and sell 100 units during the promotional period. Let’s say it’s a 30% off promotion. The retailer removes 15% of its usual gross margin, bringing its margin to zero. The producer also removes 15% from its gross margin, bringing it to zero. Both parties aim to gain market shares here.

However, the retailer will not sell all the stock during the promotional period. After the end of the promotional period, they will start selling the same product again, but this time at full price. This strategy allows them to buy stock cheaply and then sell the merchandise at full price after the promotion. This doesn’t work for ultra-fresh products with a shelf life of just a few days, but many products sold by Amsterdam have a shelf life of several weeks or more. Retailers are very good at playing these sorts of games, which is how they survive against their competing retail chains.

The third class of “gotchas” is that competitors react. When Amsterdam triggers a promotion, it tends to generate a response from its competitors. If everyone pushes promotions to the market all the time, it is akin to a price war, which hurts the profitability of Amsterdam and its competitors. From a decision-making perspective, Amsterdam needs to decide every single day which products are the right candidates for promotional activity and negotiate with one or several retail clients. Ideally, the company should instrument the negotiation so that the deal emerging from this negotiation is in the best short-term and long-term interest of Amsterdam.

Finally, co-packing refers to two different but complementary things. A co-pack is fundamentally a grouping of multiple products in one bundle, as shown on the screen, and it is also a third-party company, typically called a co-packer, that provides more or less sophisticated packaging services. Co-packing is a powerful lever for Amsterdam to adjust its production mix. Amsterdam can potentially supercharge a co-pack bundle with products that are slightly in excess in its supply chain network.

Normally, there is a bill of material, which represents exactly what is put in the bundle. However, it’s typically priced against the weight, and Amsterdam has the opportunity to slightly adjust the mix of what is found in those bundles. The interesting thing is that the bundle is both a constraint and a lever. It’s a constraint because, to produce a bundle, availability is needed for all the products that are part of the bundle. On the other hand, there is the lever side of the equation, which is the fluid bill of material that can be used as an extra level to adjust the excess or shortage that Amsterdam continuously faces in its supply chain.

In terms of the decision-making process, Amsterdam can, and should, continuously revisit the fine print of the composition of all its co-packs on a daily basis as an extra level of adjustment to avoid shortages or excess of products being processed through its supply chain.

In conclusion, while cheese is about ten thousand years old, modern cheese supply chains are very complex. As soon as you start paying attention to the details, you will see that the solutions found in most supply chain textbooks, such as safety stocks, inventory buffers, and service levels, are woefully inadequate. These numerical recipes are simplistic views of the games being played in real-world supply chains.

This lecture is illustrative of a less complex supply chain, with only 1,000 SKUs, which is a tiny fraction compared to aviation. However, we see that there are tons of constraints and levers, and things are very fluid. The only way for a company like Amsterdam to operate profitably is to stick to the base reality of its business, embracing milk chemistry and milk processing, and ensure that all the supply chain numerical recipes involved in this process have a strong affinity to this base reality.

Doing it any other way guarantees irrelevance and is most likely harmful because it will be misguided and fail to answer the right questions. All the options presented need to be continuously adjusted on a daily basis. Even with 1,000 SKUs, each SKU entails dozens of decisions that need to be quantitatively assessed every single day. In the end, the problems faced are very complex and, to some extent, quite complicated as well.

Now, I will be having a look at the questions. Before I jump to the questions, the next lecture will be a one-off lecture in the chapter of auxiliary science. I did push a survey over LinkedIn, and over 100 people said they wanted a lecture on blockchain. So, I’m going to do a lecture on blockchains for supply chain. It’s going to be a fairly technical lecture, just because I believe that most people who talk about blockchains have no clue whatsoever what they’re talking about. First, we are going to characterize what blockchain actually is, and then we’ll see, once we understand what it actually is, what sort of purpose they can fulfill as far as supply chains are concerned. We’ll see that there are a great many obstacles and questions.

Let’s have a look at some questions.

Question: If you use price to manage the supply and demand balance regarding the similar midterm where Amsterdam is one of the few large suppliers, don’t you risk that competitors are doing the same?

Well, absolutely, and that’s why you have to secure your supply of fresh milk with dairy farmers using multi-year contracts. If you don’t do that, and if a company as large as Amsterdam tries to supply fresh milk on the spot market, basically, the competitors of Amsterdam would corner all the supply and push Amsterdam out of the market altogether. Securing the supply is of critical importance, and indeed there are adversarial behaviors at large. All those companies compete for dairy farmers.

On the long term, over several years, it is relatively straightforward to adjust the overall supply up and down, but in the short term, the market is very rigid. Competitors can play the game very hard, and this is a very competitive way of practicing supply chain management.

That’s why branding is very important for a company like Amsterdam. Having a brand with very loyal consumers is a way to secure demand for multiple years, irrespective of small price variations and marginal promotions that competitors are doing. Branding and engineering a high degree of loyalty among the customer base is critical. It’s a matter of survival for a company like Amsterdam. Even if branding, in terms of image, marketing, and communication, is outside the strict scope of supply chain, the branding is a key ingredient for the supply chain to operate effectively. It engineers the stickiness of the customer base.

Question: Don’t you think when looking at promotion retrospectively, especially when promotions levels are high (let’s say 50% which is already very high), it looks like a wicked game that makes overall more harm for supply chain than good?

This is the point of competition. Companies like Amsterdam are trying to compete, and if they and other companies operating cheese brands were not trying to compete, they would collectively decide to raise the price, which is exactly what a cartel is about. A cartel is very profitable for the members, but the problem is that it results in higher prices for everyone else.

There is a balance between being too aggressive and causing harm to everyone, including yourself. Overall, for the market, it’s a good thing that companies are playing tough and competing fiercely because that ensures low prices for consumers. When deciding to do a promotion, you are in a way harming yourself on the short term, as well as your competitors. Ideally, you harm your competitors more than yourself because you want to gain market share. It is a tough game being played here, and we’re looking at a company that has only a 3% EBITDA. Margins are thin, but this is also a testament to the efficiency of the markets.

If something as basic as the production of cheese was enjoying an 80% gross margin, there would be something dramatically inefficient about the market. It would be a market ready to be completely disrupted. If a company that is very efficient still has only a 3% margin, that means the competitors are very good, and it is a very tough game being played.

Addressing the comment on 80% of the supply being sold below the base price, there isn’t really anything like a base price. There is positioning, but it’s always in flux. When you have a 20% discount, it’s just an arbitrary discount given on top of your retail price, which is also kind of arbitrary.

Question: All those elements add more layers of variance, dilute brand positioning, and lead to more buffers along the supply chains for all players.

More buffers do not necessarily result from promotions. On the contrary, promotions can be a great way to flush your buffers. To me, it looks like the perfect example of the classic prisoner’s dilemma, which I agree is a simplistic version. Taking into account that brands can communicate and that their pricing is transparent to other players, it’s not exactly the same as the prisoner’s dilemma. The game being played here is very much iterated, and what you do is very much transparent with regard to the other players. There is no such betrayal; it’s a competitive game. If you push for more market shares, your competitors have to respond in kind or eventually be pushed out of the market altogether.

Everybody plays the game, but nobody wins. This is not exactly the case here. A 3% margin is thin, but we’re talking about one billion euros worth of sales, which translates to 30 million euros worth of profit every single day. These businesses can operate with thin margins but profitably for decades, so there are winners. It’s just not like software, where companies are worth a thousand billion euros, but there are still people who are very well off thanks to these sorts of businesses.

Question: When the problem is not in the number of SKUs but in the complexity of constraints, how would the optimization approach change?

The problem, if not in the number of SKUs but in the complexity of constraints, changes the optimization approach in the sense that different numerical techniques are needed. If you go from 1,000 SKUs to 1 million SKUs, there are classes of optimization techniques that cannot scale up to millions of SKUs but can deliver results if you have just around a thousand SKUs overlaid by very complex constraints.

By the way, in the fourth chapter, there will be a lecture on mathematical optimization for supply chain that I will be giving in August. In this lecture, I will be presenting the various mathematical optimization paradigms that are available at our disposal. We will see that these paradigms vary both in expressiveness, what sort of problems can be framed through them, and scalability. To give you a more comprehensive answer to your question, I will be getting back to this lecture in August.

Question: How does the situation change for more streamlined supply chains with simpler constraints but a larger number of SKUs?

The reality is that many companies have very complex constraints. The forms and shapes that these constraints take tend to be very different from one vertical to another. My main objection is that if you think there is a large-scale business that appears to have a straightforward, unconstrained supply chain, it may be that you have not uncovered all the constraints or complexities taking place in your supply chain. Again, the goal of the World Series of Personnels is to shed light on those unsuspected complexities. Very frequently, people, especially in supply chain textbooks, approach problems with overly simplistic approaches. For example, most supply chain textbooks approach promotions as just a problem of predicting the uplift on the time series forecast. This is absolutely not the game being played.

I agree that probably other supply chains may not have such an entangled balance to maintain between supply and production, but there will be other sorts of complications that will still make the game quite challenging to play, supply chain-wise.

Excellent! It looks like I went through the questions. The next lecture will be three weeks from now, on the same day of the week, which will be Wednesday, at the same time, which is 3 PM Paris time. See you next time!