00:00 Introduction

03:53 Visions

07:49 Values

10:53 The story so far

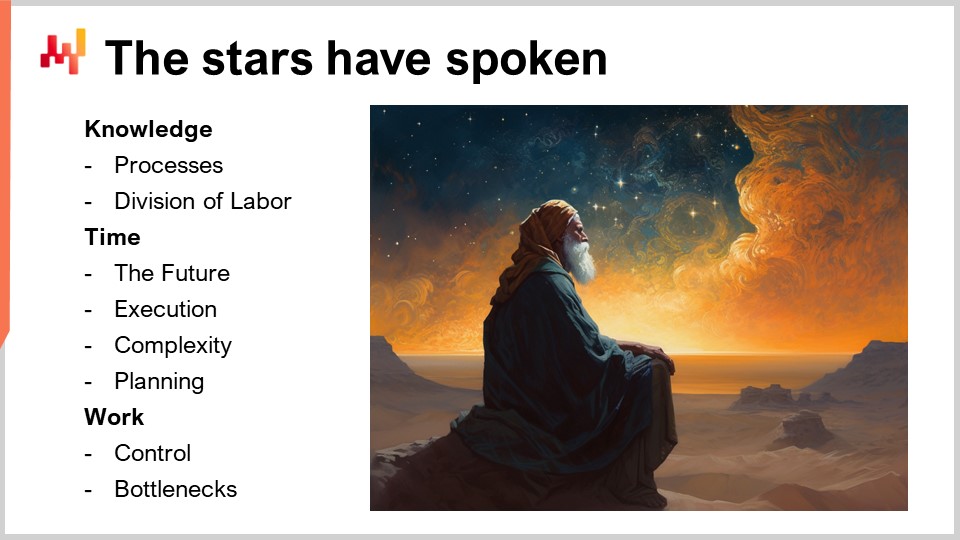

13:51 The stars have spoken

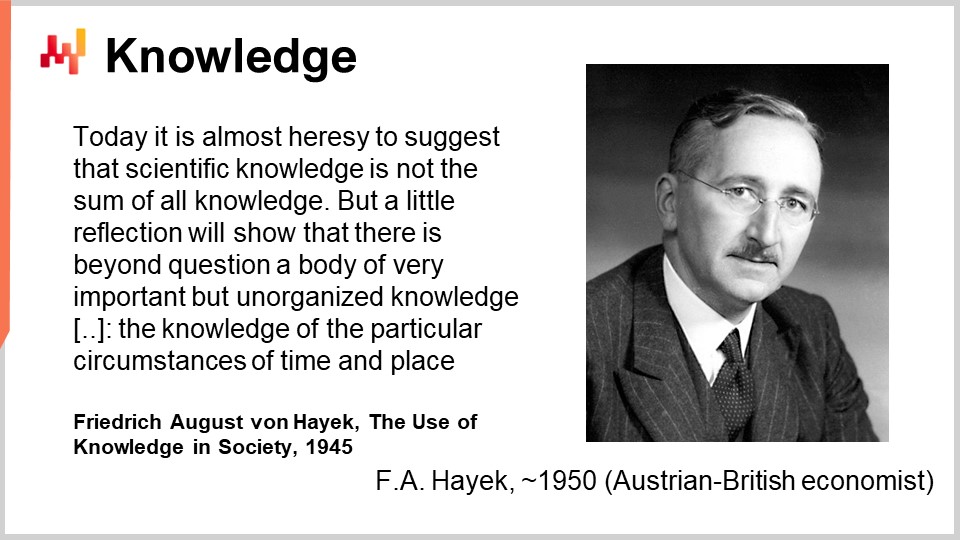

15:49 Knowledge

20:08 Processes (Knowledge 1/2)

24:32 Division of labor (Knowledge 2/2)

28:49 Time

33:23 The Future (Time 1/4)

38:16 Execution (Time 2/4)

42:48 Complexity (Time 3/4)

47:47 Planning (Time 4/4)

54:19 Work

59:57 Control (Work 1/2)

01:07:21 Bottleneck (Work 2/2)

01:12:35 Variety and validity

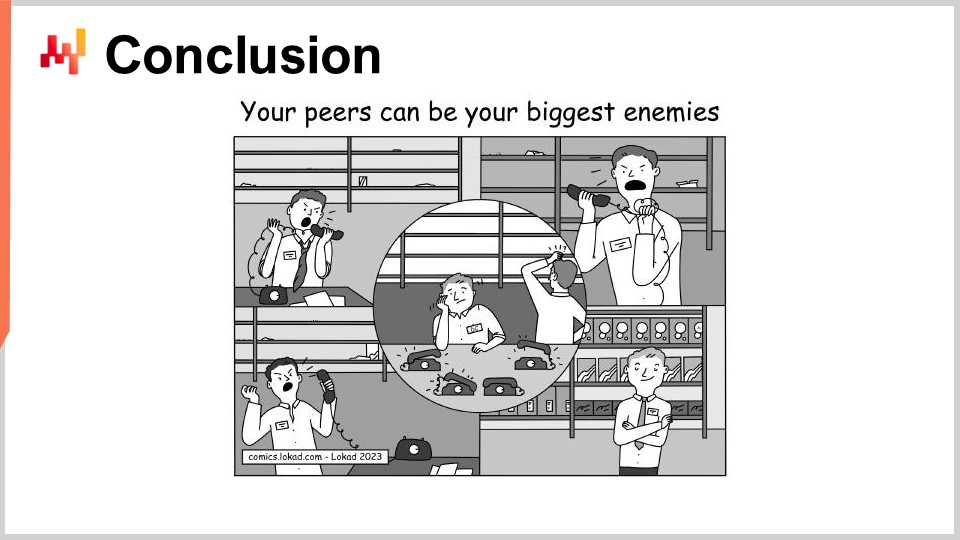

01:17:44 Conclusion

01:20:23 1.7 On Knowledge, Time and Work for Supply Chains - Questions?

Description

Supply chains abide by the general economic principles. Yet, these principles are too little known and too frequently misrepresented. Popular supply chain practices and their theories often contradict what is generally agreed upon in economics. However, these practices are unlikely to ever prove basic economics to be wrong. Additionally, supply chains are complex. They are systems, a relatively modern concept that is also too little known and too frequently misrepresented. The goal of this lecture is to understand what both economics and systems bring to the table when tackling planning problems for a real-world supply chain.

Full Transcript

Welcome to this series of supply chain lectures. I am Joannes Vermorel, and today I will be presenting on knowledge, time, and work.

When approaching supply chain management, either through textbooks or through corporate practices, much is left unsaid. Naturally, there is an element of necessity, as spelling out everything isn’t a practical option. However, there is also an element of blindness. Some critical ideas, thoughts, or insights that should have been made explicit are almost inevitably left untold and unwritten. Among all those untold ideas, the most powerful ones are those that steer our intuition of causality for the objects of interest — in this case, supply chains.

Indeed, this intuition of causality defines how we frame situations, how we see problems, and whether we see them at all. In this lecture, the term ‘vision’ refers to this intuition of causality. Vision permeates the company: its culture, its processes, and its practices. Misguided visions undermine our ability to identify the correct problems and can lead us astray, chasing solutions that may have little or no chance of ever bringing the intended benefits for the company.

These intuitions of causality, these visions, can be just as mistaken or misguided as anything else. A vision that turns out to be inappropriate for a given company can poison every single attempt at improving its supply chain, even over time, and can merely lead to a continuation of what already exists.

Furthermore, within the same company, people rarely hold the exact same vision. In fact, they might hold radically different visions. As visions are rarely spelled out, employees are too frequently left with the feeling that whenever they try to push, some other employee tries to pull in the opposite direction. We will see that the root cause behind these conflicts can frequently be attributed to a divergence of visions rather than the divergence of values or incentives.

The two propositions that I will be defending in this lecture are subtle and yet critically important.

First, there are powerful visions floating in supply chain circles. These visions permeate and shape both the field of study—the theories, the books, the papers published about supply chain— and also the practices, including the supply chain processes and the supply chain software technologies. Far from being a minor detail, these visions massively impact companies that operate supply chains, as well as their supporting ecosystem, which includes universities, software vendors, and consultants. We will be reviewing a series of such visions in this lecture.

Second, not all visions are equally effective or appropriate for the betterment of supply chains. Some widely held visions are even detrimental to the efficiency and reliability of supply chains. By the end of this lecture, you should be able to identify at least some of the visions at play in a given company and be equipped with a few intellectual instruments to challenge the validity of those visions.

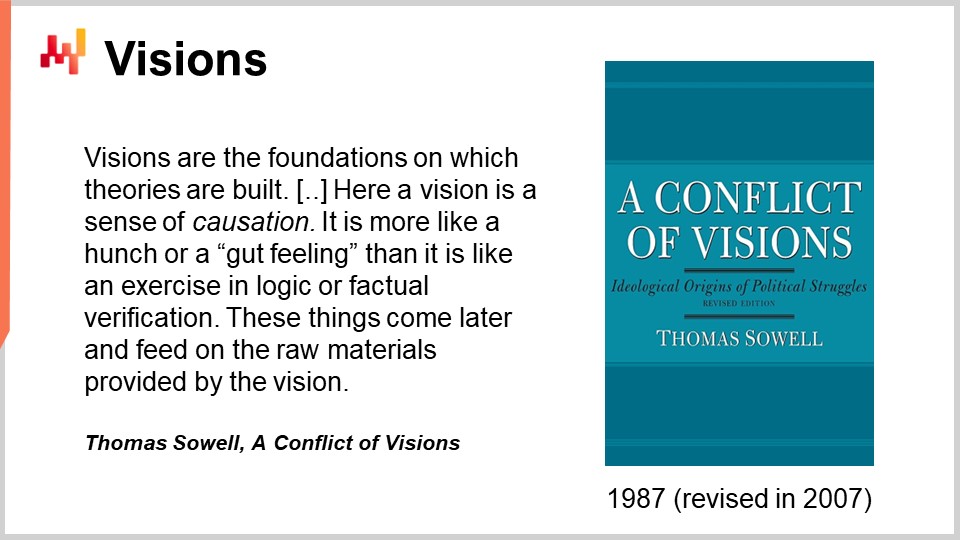

In “A Conflict of Visions,” Thomas Sowell introduces his concept of ‘vision.’ He describes it as an intuitive or unconscious understanding of how the world works. These visions profoundly shape our immediate and instinctive understanding of society and the universe at large. Sowell states, and I quote, “It is what we sense or feel before we have constructed any systematic reasoning that could be called a theory. A vision is our sense of how the world works.”

Visions are to some extent simplistic, although that is a term typically reserved for other people’s visions, not our own. Visions largely condition how we approach complex systems—systems that are beyond what a human mind can readily comprehend. While the book “A Conflict of Visions” focuses on the complex system that society represents, this lecture focuses on supply chains.

For example, let’s consider a retail store struggling with maintaining adequate stock levels, leaving half of its shelves empty. The instinctive assessment of the probable root causes of this situation will vary greatly depending on the vision that one holds about the supply chain and how it should function.

Take a professor of supply chain analytics, for instance. He may instinctively attribute the empty shelves to inaccuracies in the demand forecast. Here, the vision places the onus of the quality of service on a technological solution, on a piece of software. This vision extends to the broader academic community, whose research contributions influence the design and the accuracy of those pieces of software, hence reinforcing this technologically centered vision.

In contrast, a regional manager within the same retail chain may instinctively lay the blame on the store stewardship, the people. In this vision, the store manager and the staff are responsible for ensuring that the store is run properly. The responsibility, according to this view, lies first with the people who are closest to the problem. An extension of this vision implicates the upper management, as they are the ones allowing this ineffective store manager to persist in his position, underlining again a people-focused vision.

It is striking that these two visions, arising from the same empty shelves in the same store, assign responsibility, and consequently resolution, to entirely different entities. One turns to a technological solution, the other to a leadership assessment. Naturally, whether the problem that the store is facing effectively derives from a faulty piece of software or from improper leadership is another matter entirely. Visions don’t prove anything; they just condition our immediate assessment of complex situations.

This divergent attribution of responsibilities showcases the significant influence that vision exerts on supply chains. As we’ll see in this lecture, alternative visions not only result in diverging assessments and resolutions of certain situations but in conflicting assessments and resolutions, often leading to mutually exclusive paths.

In politics, as well as in business, leaders often highlight their own values to underscore the differences between themselves and their rivals. The phrase “we do not have the same values” can be heard on all sides. However, this perspective, while not without merit, tends to obscure the profound influence of visions.

Note that when individuals encounter varying interpretations of the same facts, they often attribute differences to divergent values. Yet, often the variation in values is far more pronounced than what the catchphrase “we do not have the same values” may suggest. In the political realm, for instance, one would be hard-pressed to find anyone advocating for poverty, crime, or war. Yet, despite shared values against these ills, people’s visions guide them towards strictly different solutions.

This observation remains valid in the realm of supply chains. Irrespective of their particular field or sector, companies universally prioritize quality of service, profitability, growth, and reducing waste. Companies that openly oppose such widely acknowledged values are extremely rare. However, alternative visions among companies result in widely different strategies and practices, all aimed at achieving the same common values.

Consider Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, who has often emphasized his, and by extension, Amazon’s relentless focus on the customer. He once said, and I quote, “The most important single thing is to focus obsessively on the customer. Our goal is to be Earth’s most customer-centric company.” Of course, this is a statement of values. However, how frequently do we see corporate executives publicly devalue the importance of customers? The answer is almost never. When an executive happens to be caught doing that, this person rarely stays in his position afterward.

What distinguishes Amazon is not its espoused values, which align with most businesses, but its unique vision and culture. Therefore, as we progress in this lecture and re-examine more supply chain examples, it is critical to remember that while companies may pursue remarkably different paths, they often seek similar outcomes: growth, profitability, and public approval of their mission. The vision and culture, not their values, differentiate their course of action.

This present lecture is part of the first chapter of a series of supply chain lectures. However, this series has already progressed well beyond the first chapter, and I am today merely revisiting and refining the very foundation that supports the later lectures. For those of you who might be interested in understanding the far-reaching conclusions of the visions that underlie the practice of supply chain as practiced by Lokad, I invite you to proceed forward with the other lectures.

In this first chapter, we have seen why supply chains must become programmatic and why it is highly desirable to put a numerical recipe in production. The ever-increasing complexity of the supply chains themselves makes automation more pressing than ever. In addition, there is a financial imperative to make the supply chain practice a capitalistic undertaking as well.

The second chapter is dedicated to methodologies. Supply chains are competitive systems, and this competition necessitates a methodology that doesn’t assume that parties operate without their own agenda while attempting to improve a given supply chain.

The third chapter surveys the problems, setting aside the solution through supply chain personnel. This chapter attempts to characterize the classes of decision-making problems that have to be solved. It shows that simplistic perspectives, like picking the right stock quantity for every SKU, don’t fit real-world situations. There is invariably a depth in the form of the decisions.

The fourth chapter surveys the elements that are required to apprehend a modern practice of the supply chain, where software elements are ubiquitous. These elements are fundamental to understanding the broader context in which digital supply chains operate. Many supply chain textbooks implicitly assume that their techniques and formulas operate in some sort of vacuum, which is not the case.

Chapters 5 and 6 are dedicated to predictive modeling and decision-making respectively. These chapters collect techniques that work well in the hands of supply chain scientists, featuring machine learning techniques and mathematical optimization techniques.

The seventh chapter is dedicated to the execution of a quantitive supply chain initiative. We see what it takes to kick off such an initiative while laying out the proper foundations. We also see who it takes to do that, namely the supply chain scientist. Finally, we see how to cross the finish line, putting the numerical recipe in production.

Today, in this lecture, we will see how visions unfold for supply chains, considering three foundational concepts: knowledge, time, and work. Divergent visions on each one of these three concepts lead to a series of conflicting appreciations on what is considered as desirable for a given supply chain.

While it is probably self-evident to this audience that a vast supply chain requires an equally vast amount of knowledge to be adequately operated, the very form and nature of this knowledge is hardly ever questioned. Yet, there are two potent alternative visions for knowledge: the special and the mundane, leading to nearly opposite views on processes and on the division of labor.

Also, time is of the essence for supply chains. Yet, two potent visions collide when it comes to the appreciation of the time dimension: the static view and the dynamic view. We will see how these two visions for time itself unfold when appreciating the future, the execution, and the complexity of supply chains. These appreciations coalesce into two radically different views on how planning should even be approached.

Finally, supply chains entail work, and more specifically, white-collar work, following the division given to supply chains in this series of lectures. However, in this digital age, people can either be seen as directly or indirectly responsible for the work, leading to very different views on the role and purpose of software technologies. We will see how these divergent visions of work itself ramify on control and bottlenecks within the company.

In the realm of supply chain, knowledge plays a crucial role to ensure efficiency. It is imperative to possess dependable insights on customer demand, on supplier constraints, in addition to a myriad of other factors. Within this context, our first major difference in visions concerns the nature and locus of this knowledge. We shall categorize this knowledge into two types: the special and the mundane. Introduced by Friedrich Hayek in his seminal work “The Use of Knowledge in Society” published in 1945, this distinction between special and mundane knowledge provides us with a foundation for understanding why different visions might result in divergent perceptions of how a supply chain should operate.

Spatial knowledge encompasses techniques, formulas, statistics, and software. In essence, it is information that is codified, structured, reviewed, and refined. This knowledge is not restricted to academia. Within an organization, codified procedures and numerical recipes used to guide the supply chain operations also count as special knowledge. A prime example of special knowledge is the Wilson formula, the formula to compute the EOQ, the Economic Order Quantity.

Mundane knowledge, on the other hand, refers to everyday trivia, that is, particular circumstances of time and place. And although increasingly recorded due to the ubiquity of computers in all shapes and forms, this knowledge remains raw, unorganized, and unrefined. It is also decentralized, that is, spread over all the employees of the company. For example, knowing that one of the delivery trucks requires brake repairs is a piece of mundane knowledge.

The two visions we discuss here emphasize one form of knowledge over the other: the special versus the mundane. Although both camps readily acknowledge the existence and the relevance of the alternate form of knowledge, they differ radically in the weight they attribute to each form of knowledge. Those who emphasize special knowledge tend to view problems, including supply chain issues, as best addressed by experts. They perceive special knowledge as a product of reason and thus they place a high premium on consistency. On the other hand, advocates of mundane knowledge believe that problems are best addressed by those who are closest to the situation. Mundane knowledge, acquired through simple observations, places importance and trust in diligence.

Both forms of knowledge have significant implications for supply chain. However, proponents of each vision often find themselves talking past each other when addressing these issues. Consider, for example, a supply chain professor and a warehouse manager. The professor might overlook the importance of maintaining the braking system of the delivery trucks, deeming it irrelevant trivia hardly worth mentioning in academic supply chain literature. Yet to the warehouse manager and his team of drivers, this knowledge can be a matter of life and death. In contrast, they might view the EOQ formula as inconsequential, yet neglecting the proper sizing of shipments leads to wastefulness, causing inefficiencies of resources including fuel, trucks, and drivers.

Let’s further illustrate these diverging visions with two examples of prime relevance for real-world supply chains: processes and the division of labor. These examples illustrate how alternative visions lead to mutually exclusive paths for companies.

The relative emphasis placed on special and mundane knowledge gives rise to markedly different perspectives when it comes to the processes of the organization. Those who favor special knowledge tend to look at the supply chain system from the top, identifying problems and seeking optimized solutions for these problems. The epitome of this perspective can be seen in the forecasting competitions, where the problem is clearly defined - extrapolate the time series into the future - and where the scoring metric removes all ambiguity about what constitutes the best solution. In this view, the presentation of the problem is seen as the easy part. The real challenge lies in finding the solution. Proponents of special knowledge value research and engineering, employing reason as their guiding principle. They lean heavily on the decomposition of complex processes into a series of manageable sub-problems.

Conversely, those who emphasize mundane knowledge take a much more grounded approach. They advocate for paying close attention to the fine print of the situation, the circumstances of time and place. Such individuals may see value in the way things are done. For instance, a seemingly simple act like visually inspecting packages as they are offloaded from a truck may address numerous unarticulated and unwritten problems. Proponents of the mundane knowledge value practices, mentoring, workshops, training sessions. They see knowledge as fundamentally derived from experience and they place a premium on holistic approaches - that is, on ways of doing things.

This divergence in views can generate significant frustration, particularly when the opposing camps do not fully realize the existence of the fracture lines. Visions are rarely made explicit. I have often seen supply chain professors, archetypes of the special knowledge camp, frustrated by their perceived lack of cooperation from companies. From their perspective, they are offering help to solve difficult problems, asking only for a list of these problems to be communicated by the company. Yet, from the viewpoint of company managers, typically more aligned with the mundane knowledge camp, the company’s processes have evolved organically over time, drawing on the experience of numerous predecessors. The ways of the company have rarely been defined in terms of solutions to specific problems. Rather, they are the product of countless judgment calls made over the years, and they embody the collective experience of the managers, including those who have already left the company.

While these two viewpoints naturally complement each other, the reality is often less harmonious due to the lack of mutual understanding of the underlying visions. Enterprise software vendors, who firmly belong to the special knowledge camp, routinely express their frustration with the shifting requirements of their clients. Meanwhile, managers may find themselves adrift in a sea of outdated practices and accumulated inefficiencies. These challenges are symptomatic of the misalignment and communication gaps that are the products of divergent visions.

As a side note, for its practice of the quantitive supply chain, Lokad attempts to bring together these two visions, emphasizing the importance of discovering the problems themselves. Contrary to the mainstream view of the special knowledge camp that takes problems as a given, Lokad’s supply chain scientists are tasked with surfacing the true problems - an approach that is treated as an experimental undertaking. This methodology is further explored in lecture 2.1, “Experimental Optimization.”

Any successful enterprise outgrows, at some point, the expansion of its supply chain. What a few employees can readily manage, larger companies must adopt strategies for the division of labor to effectively distribute the workload across a larger workforce. For the purpose of our discussion, I will introduce two strategies: the horizontal and the vertical division of labor.

The horizontal strategy involves partitioning work by function, where each function serves the entire business. For example, in a retail chain, we might see departments such as purchasing, planning, pricing, or merchandising. On the other hand, the vertical strategy divides labor by market segments, where each employee is overseeing all aspects of their respective segments. In a fashion company, for example, an employee might be responsible for the entire leather accessories category, encompassing sourcing, buying, planning, pricing, and merchandising.

In reality, companies seldom adopt a purely vertical or purely horizontal strategy. Many opt for a blend of both. However, the predominance of one over the other is strongly influenced by the dominant vision favoring specific knowledge or mundane knowledge within the organization. Those favoring special knowledge tend to prefer horizontal division, thereby promoting the role of experts. These are individuals who possess a deep understanding or mastery of a narrow challenge. Roles in forecasting and in data science exemplify this. Such horizontal divisions highlight the role of experts, individuals who are accountable for the performance of their business units, such as a store manager in a retail chain responsible for a store’s overall financial health.

Conversely, those leaning toward mundane knowledge are inclined to prefer vertical divisions. However, neither strategy can claim universal superiority, as both come with their own merits and demerits contextually dependent on the company’s specific circumstances. Over-reliance on experts might disregard the potency of simpler solutions in favor of more sophisticated ones that prove more fragile and costly. Meanwhile, placing too much faith in leaders might lead to overestimating what naked diligence and discipline can bring to the company without the support of further competitive edges.

The importance of a nuanced understanding of the nature of knowledge should not be understated. I have personally witnessed large organizations embark on extensive transformation plans, frequently transitioning from a dominantly vertical organization to a dominantly horizontal one, without adequately considering the comparative values of experts and leaders in their specific circumstances. This inevitably leads to less desirable outcomes.

As a tangent note, from the perspective of the quantitative supply chain, Lokad seeks to enhance the productivity of the white-collar workforce during the supply chain. The goal is not just to reduce cost, although that’s a welcome outcome, but to defragment responsibilities within the organization. The role of the supply chain scientists, as defined by Lokad, assumes responsibilities that are both broader and deeper compared to mainstream supply chain practices. This topic is explored further in lecture 7.3, “The Supply Chain Scientist.”

Time, or more precisely, timing, is of the essence for the supply chain. If we lived in a world where goods could be instantly 3D printed and teleported to their destination, timing would lose much of its significance. However, as it stands, managing a supply chain involves a series of delays, typically referred to as lead times, often requiring preparations months in advance. Yet time is elusive and our understanding of it, as it relates to time, even more so.

In the book “Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder,” published in 2012, Nassim Taleb posits two contrasting views of time: the static view and the dynamic view. Although Taleb’s book is primarily focused on antifragility, it’s these two visions of time that pertain to our discussion here. The static vision perceives things as if they were frozen in time, in a snapshot, viewed in isolation. It advocates a mechanistic perspective of the universe where any system, including supply chains, can be decomposed and modeled according to the static view. Given the system parameters at a point in time, we can predict its evolution. In practice, our ability to measure all these parameters might be limited, but conceptually, nothing prevents us from further dissecting each phenomenon and refining our measurements in order to improve the accuracy of our predictions.

In contrast, the dynamic vision interprets systems as collections of agents. It sees interdependencies and feedback loops. It recognizes the world and many of its systems as chaotic. Moreover, the changes brought by these agents don’t occur solely due to universal laws, like the motion of planets, but also reflect the intention of individuals. Hence, any prediction a model makes can be unmade by people once they become aware of the prediction. The predominant perspective in mainstream supply chain circles, in academia, in enterprise software, and among supply chain practitioners, is the static vision. It emphasizes deterministic time series and demand forecasts, while other uncertainties such as varying lead times or varying returns are treated as defects to be eliminated. The static vision also comes with sharp delimitations on what is considered as a supply chain challenge and what is not.

Meanwhile, the dynamic vision, as laid out by Taleb, remains to the present date largely absent from the mainstream supply chain circles. However, this dynamic vision does align with the quantitative supply chain as advocated by Lokad. Lokad’s perspective emphasizes a probabilistic forecast, accounting for all sources of uncertainty. Lokad’s perspective also remains somewhat elusive about what should be considered a supply chain challenge, favoring empirical, if not opportunistic, criteria over predefined boundaries. For instance, from Lokad’s viewpoint, pricing and advertising may fall under the supply chain purview, although without claiming exclusive ownership of those topics.

In our earlier discussion contrasting special and mundane knowledge, both visions had their respective strengths and weaknesses, resulting in a relatively balanced presentation. However, there is no inherent balance or complementarity to be found among competing visions. Some visions may happen to be woefully inadequate to support supply chain undertakings. As we will see, the static vision, despite its popularity, is one of those woefully inadequate visions.

Let’s see how these two visions, the static and the dynamic, imply for the future, the execution, and the complexity and, finally, the planning of supply chains.

Every action, every allocation of resources within the realm of supply chain, reflects a forward-thinking approach, an anticipation of future events. Yet, the interpretation of the future is a point of divergence between the static vision and dynamic vision, both of which have far-reaching implications for supply chains.

Adherents of the static vision perceive the future in terms of forecasts, more specifically, periodic time series forecasts. They deem the future as fundamentally knowable and symmetrical to the past, a perspective shared with Newton in physics. The inaccuracies of those forecasts are attributed to poor processes, lack of cooperation, bad data, flawed forecasting models - in other words, they are remedies. Forecasts are only accidentally inaccurate. Furthermore, sources of variations such as lead times, returns, or commodity prices are perceived as defects to be eliminated or, at the very least, to be put under control.

However, proponents of the dynamic vision interpret the future in terms of risk. The uncertainty associated with the future is fundamental; it is irreducible. While the future isn’t entirely unknowable, at best, it’s going to be only guesses and probabilities. In the dynamic vision, the future isn’t a mirror of the past but contingent upon decisions that have yet to be made. From this perspective, the central problem isn’t so much improving the forecasting accuracy but rather surveying all the hidden risks and hidden opportunities, leaving no stone unturned. The concept of risk encompasses not just customer demand but also suppliers, transporters, competitors, etc.

The roots of the static vision can be traced back to the early forecasters of the 20th century such as Roger Babson, who sought to transpose the predictive capabilities of astronomy to the economy, with the stated goal of achieving near perfect anticipation of demand and price fluctuations. This view remains central in supply chain literature and in the software industry, where time series forecasts remain the cornerstone of planning practices and planning software.

As a side note, certain business philosophies like Kanban, lean management, or the five zeroes of Toyota do not exactly fit into either the static vision or the dynamic vision. They perceive the future as somewhat unknowable, similar to the dynamic vision, and downplay the emphasis on time series forecasting. Yet, these philosophies still align with the static vision by treating all variations as defects rather than risks and opportunities. Consequently, these philosophies sidestep the question of the future rather than providing any substantial answer. Even Toyota, as of this year 2023, despite its principle of zero stock, is holding nearly 30 billion dollars’ worth of inventories, hardly qualifying as zero stock.

My proposition is that the static vision, despite its prominence, is misguided. Even after nearly a century since Babson’s era, the question remains: has the progress in forecasting techniques truly rendered the supply chain more certain? Over a decade and a half at Lokad, I have interacted with over 200 companies striving to rectify their inaccurate forecasts, but not one has ever come close to achieving this goal in any meaningful way. Furthermore, companies often overlook factors like pricing that have a major impact on demand. Most treat forecasting and pricing as two independent undertakings, reflecting an academic practice in the supply chain literature where pricing is seldom mentioned, let alone given a dedicated chapter in a supply chain book. This single misguided vision about the future is, I believe, one of the most significant factors impeding the progress of the entire field of supply chain.

The execution of supply chains covers a myriad of mundane actions to be performed daily. There are orders to be placed, inventories to be fetched, production batches to be completed, goods to be shipped. This endless stream of action is guided by our perception of the future. The divergent outlooks on the future, namely the static and dynamic visions, lead to conflicting strategies when it comes to the ongoing execution of action for supply chain purposes.

Those adhering to the static vision see the execution as a grand symphony of orchestration. Under this perception, the forecast serves as the music score, providing the rhythms and notes that govern every action, every allocation of resources. Disruptive nodes of non-linearities like MOQs (Minimum Order Quantities) disrupt the harmony, but they are expected to be smoothed through mathematical optimization, preserving the symphony’s integrity.

In contrast, the dynamic vision sees the execution as a matter of opportunistic prioritization. Every decision presents its own risk and its own benefits, which must be weighed not only in isolation but also against the risks and benefits associated with alternative decisions. This guiding principle is not an adherence to a pre-determined symphony but the management of an opportunistic decision-making process based on shifting priorities. Non-linearities like MOQs are more readily accommodated under the dynamic vision. They are perceived as factors that modulate the associated risk rather than disruptors of the symphony. If the risk of excess inventory caused by a large MOQ outweighs its benefits, the order is simply not placed. There are no absolute requirements to conform to any specific forecast. The dynamic vision does not eschew optimization techniques, but it uses them as tools to manage risk rather than to enforce compliance to a forecast.

The orchestration model of the static vision is the direct result of its perception of the future as a known quantity. Decisions aren’t really being made; actions are essentially predetermined by the forecast. For example, safety stocks are the embodiment of the static vision. Safety stocks operate on the assumption that inventory levels should adhere to a plan, deviating only within an acceptable measurement tolerance.

This approach contradicts basic economics. As the British Economist Lionel Robbins defined in 1942, economics is the study of the use of scarce resources which have alternative uses. Economics tells us that we have to pay attention to what those alternative uses actually are. Safety stocks treat products in complete isolation. The only alternatives are to buy more or less of the same product. However, basic economics tells us that every stock unit to be acquired for a given product competes for the same pool of resources with the acquisition of alternative stock units associated with other products. Hence, safety stocks disregard basic economics.

On the other hand, prioritization, which lies at the heart of the dynamic vision, is the embodiment of this fundamental principle of economics. Prioritization treats resources as scarce. It assumes that there won’t be enough resources to support every desirable decision. Prioritization exists so that choices can be made.

Now let’s venture to our next point of divergence between the static and dynamic vision, focusing on complexity. Afterwards, we shall witness how these divergent perspectives culminate into drastically different strategies for planning modern supply chains.

Modern supply chains represent a ceaseless flux of movements and transformations of goods and materials that vastly exceed what a single human mind can readily comprehend. Therefore, we need methods and techniques to consolidate these flows into digestible insights, making the supply chain manageable and its improvement discernible. However, depending on one’s perspective on complexity and its relationship with time, two contrasting views emerge: segments and archetypes.

Those subscribing to the static vision approach complexity through segmentation. They feel that complexity can be tamed, and a supply chain in particular can be tamed by dividing it into smaller, manageable segments, each behaving consistently over time. This approach effectively removes the time dimension from the picture. An example of this is the ABC analysis that segments products or SKUs based on their sales volume. The intent of the ABC analysis is to attribute higher service levels for higher volume classes and lower service levels for lower volume classes.

On the other hand, proponents of the dynamic vision approach complexity through archetypes. Archetypes encapsulate the typical evolution of the element of interest through their respective timelines. For example, a book is expected to have peak sales at its launch, with sales declining sharply afterwards. Later, notable events such as the death of the author may trigger further transient peaks in sales volume.

This divergence in views - segments versus archetypes - is not unique to supply chain. It echoes a long-standing series of confusion that economists clarified almost a century ago. Let’s consider this through an example: the media often speaks of the rich and the poor as segments within the population. The static vision assumes that these groups remain constant and consistent over time, just as it does with the ABC classes. However, a closer look paints a different perspective. Consider the fresh graduates of Harvard Law School, who, with an average debt of $170,000, are technically classified among the poorest in the United States. Yet, their earnings will put them in the top 10 percent of earners, irrespective of age, right after graduation. Similarly, a barber who sells his boutique for one hundred thousand dollars upon retirement will be in the top 10 percent of earners that year, thus technically classified as rich, although he has spent his entire career earning less on average than his fellow Americans. As pointed out by Thomas Sowell in his book “Basic Economics,” the fate of brackets and the fate of people can be very different, and in many cases, completely opposite.

This principle applies equally to supply chains. One can simply replace people with products, clients, or suppliers. Segmenting products into classes A, B, and C, as done in the ABC analysis, confuses rather than clarifies the situation. The same issues arise with any segmentation, whether based on sales volume, profit, or growth. It is the segmentation itself, as a process, that is at fault, precisely because it attempts to remove time from the picture. The segmentation process itself is at fault precisely because it attempts to remove time from the picture of the system. In contrast, archetypes come with a story, a story of what happens over time. Archetypes magnify the temporal aspects. As a rule of thumb, whenever we are presented with the options of taming complexity, gaining insights through archetypes, like Harvard graduates or barbers, are preferable to segments like the rich and the poor. While both represent drastic simplifications of the underlying reality, archetypes are useful to appreciate the future, while segments are a constant source of confusion.

Now that we have touched on the execution and complexity of the supply chain, let’s see how these visions coalesce into two radically different views on planning.

The concept of planning plays a pivotal role in the field of supply chain. The process involves determining goals and charting out the steps required to attain them. It is essentially a predictive exercise where future events or conditions are anticipated and where the required resources and actions are arranged to manage them effectively. This proactive method of dealing with future circumstances has made planning an integral part of supply chain practices.

The static and dynamic visions lead to conflicting takes on planning and drastically different outcomes in practice. The static vision approaches planning as a two-step process. First, forecast demand; second, orchestrate the supply to meet the demand. If the complexity exceeds what can readily be managed by a single planner, then introduce as many segments as it takes to spread the workload over the adequate number of planners. This vision permits the quasi-totality of the supply chain literature and the quasi-totality of the supply chain software as well. It operates on the assumption that accurate forecasts will be achieved, and thus unlocking superior supply chain performance in turn. This vision has held an immense appeal for intellectuals over the past century and has been the cornerstone of most government and corporate planning strategies.

However, we must question the validity of this vision for planning itself, a question rarely raised, much less answered. In this regard, history provides quite an abundance of facts about the adequacy of this form of planning, typically referred to as central planning when done by a government. The USSR can be seen as a 70-year long demonstration of the inadequacy of the static vision when it comes to planning. Critics may argue that the USSR was unique due to its colossal scale, however, let’s consider that at its peak, the Gosplan, the board overseeing the USSR’s planned economy, was supervising 24 million products. However, back in the early ’90s, quite a few distributors in Europe were already individually distributing over 1 million distinct product references.

Scale by itself doesn’t necessarily doom the planning undertaking. It is how planning is approached that matters. None of those distributors were even attempting to operate through five-year plans like the USSR was doing. Similarly, the static vision of planning pervades S&OP (Sales and Operations Planning) within large corporations, often culminating in exceedingly bureaucratic endeavors. Ingvar Kamprad succinctly captured this sentiment in his “Testament of a Furniture Dealer,” published in 1976, cautioning his employees that edicting planning is the most common cause of corporate death. This is the static vision of planning that Ingvar Kamprad is referring to here.

Indeed, large corporations frequently initiate grand reorganizations to improve planning, embracing the static vision, but rarely end up surpassing their peers in any meaningful way through such undertakings. On the contrary, failures in planning are dwarfing, both in frequency and in magnitude, the successes. The failed planning initiatives at Nike in the 2000s or at Lidl a decade later, where i2 and SAP projects respectively led to massive losses, counting in hundreds of millions of dollars and euros, stand as testament to this fact.

In stark contrast with the static vision, the dynamic vision sees planning as a process of risk assessment and prioritization. It embodies an opportunistic enterprise spirit, a far cry from the sterile scientific vibe of the static vision. Planning itself is de-emphasized. Instead, it’s seen as a step toward making the right decision at the right time. The plan in the dynamic vision is inherently disposable and shifting properties are commonplace. This ability to swiftly adapt to changes through constant and incremental reprioritization is a stark contrast to the cumbersome process involved with the static vision of planning, which requires a wholesale re-planning exercise to accommodate any change.

While the dynamic vision is often deemed as unsophisticated or crude, as it neither offers nor relies on a predetermined future, it can benefit from advanced techniques and algorithms just as much as the static vision can. In fact, e-commerce giants like Amazon function primarily through algorithms that dynamically allocate resources, treating the forecasts themselves as nothing more than transient computing artifacts, attesting to the severity of the dynamic vision.

However, these techniques diverge fundamentally in their focus. The dynamic vision, as implemented by Lokad, employs probabilistic forecasts instead of classic deterministic forecasts. But the term ‘forecast’, just like ‘planning’, is so closely associated with the static vision that it might sound like a mere technical variation of the same thing. It is not. A more appropriate term for probabilistic forecasts would be ‘quantitative risk assessments’, which more resiliently capture the essence of the dynamic vision when it comes to planning. Chapters 5 and 6 of this series of lectures delve into the techniques that support planning when approached with the dynamic vision. Those techniques are beyond the scope of the present lecture, but I encourage the audience to explore them if you’re looking for a form of planning that actually works.

Speaking of work, in this series of lectures, we define supply chain as a white-collar activity, not to be confused with logistics, a blue-collar activity. For example, deciding what to ship, when, and where is a matter of supply chain, while driving the trucks to make it happen is a matter of logistics. However, the very notion of work, just like time and knowledge, is strongly dependent on the underlying vision, whether it’s direct or indirect.

For those who adopt the direct vision, work is characterized by a list of tasks and duties that employees are expected to fulfill. For example, the tasks of the supply chain practitioner may include passing timely purchase orders, scheduling the production batches, and refreshing the weekly demand forecast. Under the direct vision, the existence of a work routine is a given. In fact, the capacity for an employee to carry out this routine diligently very much defines the quality of the work delivered by the employee. Furthermore, assessing the quality of the work can be carried out at the individual level. While supply chain is a collective effort, each employee has his or her own well-defined scope of responsibility, and through this scope, the performance of the employee can be measured in relative isolation from the rest of the company.

For those who adopt the indirect vision, work is performed by machines. This vision matches the old IBM principle: “Machines should work; people should think.” People are not expected to do the actual work, but to engineer, supervise, and possibly improve the automation that does the work. The existence of any kind of routine on the human side is seen as a defect, as a lack of automation. Why would anyone do a second time what should have been automated in the first place? In fact, the capacity of an employee to keep improving the automation, to keep lowering the need for manual intervention, largely defines the quality of the work delivered by this employee. As the automation itself is the product of many minds, it’s not even conceivable to measure individual performance in supply chain terms. All contributions blend into the same automation. Thus, the assessment of the quality of the work delivered by an employee is fundamentally a judgment by peers: are the contributions of this employee superior or inferior in quality and criticality to the ones delivered by the other employees?

In this age of digital supply chains, there are no companies left that would still qualify for a pure form of the direct vision of work. Even spreadsheets, as crude as they may be, let employees delegate a sizable portion of the actual work to machines. No manager expects their employees to manually perform any kind of arithmetic calculation anymore. Conversely, not even the most advanced companies can claim any kind of truly autonomous supply chain, at least not yet. Thus, the indirect vision remains interleaved with direct interventions from employees.

However, visions are more about what should be rather than what is, and whether executives lean on the direct or indirect vision can have profound consequences for the company. At this point in this series of lectures, it should not come as a surprise that the quantitative supply chain, as advocated by Lokad, is firmly set in the indirect camp. However, it would be uncharitable to present the direct vision as some vestigial bastion of a bygone era, while putting the indirect vision on a pedestal as the pinnacle of modernity. Both visions have merits.

Those two visions tend to conflict on a broad range of topics when it comes to picking directions for a given supply chain. The main argument proposed by Lokad in favor of the indirect vision is to turn the supply chain practice into a capitalistic undertaking. This argument was presented at length in the first lecture, “1.3 Product-Oriented Delivery”. Revisiting the fine print of this argument is beyond the scope of the present lecture, but suffice to say, automation offers a possibility to not only dramatically reduce the amount of labor required to operate the supply chain but also offers a possibility to engineer the supply chain beyond what the most dedicated employee could achieve.

However, sources in favor of the direct vision would argue that this indirect vision is technocratic and it exposes the company to new classes of risk, including the risk of letting the company bury itself into the ground by putting it into the hands of engineers, who have a serious tendency to lack common sense as far as business is concerned. Moreover, the diffusion of individual responsibility into strictly collective effort, as it happens with most software projects, paves the way for all sorts of problems that can’t be resolved anymore by firing the person who caused the problem in the first place. Now, let’s explore what the direct and indirect visions entail in terms of control and bottlenecks.

Control can be understood in two ways. Here, we are referring to the layman’s understanding, as in “keeping things under control”. Control is how management enforces its will upon the organization. Control in the supply chain isn’t born out of any inherent desire of top management to be some sort of despots within their own organization, but out of practical necessity. Supply chain, generally speaking, involves a careful act of balancing the demand generated by the company with what it supplies, that is, the resources allocated to meet this demand. As this act of balance is typically spread over many people, control is needed to avoid elements within the organization from derailing this process, usually unintentionally.

Exercising control is a central aspect of the work expected from the management of the supply chain. However, depending on the vision one has over the nature of work, control entails very different things. For those who adopt the direct vision, control is primarily exercised following a “trust but verify” mindset. Directions are given through the chain of command as defined by the organization, and people will be implicitly trusted to do their best to follow those directions. However, the trust isn’t blindly given. Managers down the chain of command must be able to verify the adequacy of the rollout as executed by their subordinates. In this age of digital supply chains, “trust but verify” comes with the expectation that the applicative landscape should provide reports, dashboards, and all other forms of data visualization. The applicative landscape may also include spreadsheets devised by the managers themselves to support their own bespoke verification processes. In other words, the direct vision, far from being opposed to software technologies, comes with its own specific set of expectations from the applicative landscape. For example, these expectations include Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), but also alerts and exceptions. These expectations reflect the vision of the sort of work that management should be doing.

On the other hand, for those who adopt the indirect vision, while control is also a practical concern, it is a concern of a completely different kind. By default, software has no control over anything within the company. It takes a carefully well-crafted, well-integrated IT infrastructure to make such control possible. Thus, from this perspective, control means first and foremost a well-integrated applicative landscape. Through this integration, it becomes possible for the automation to operate. Without it, there is not even the possibility of control, as there is no work that is even happening.

A well-integrated applicative landscape is not just a possibility to inject commands or orders into specific subsystems, it is also the capabilities required to audit and troubleshoot any dysfunction, either by retrieving historical data from subsystems or by injecting commands into them. Conversely, controlling the automation itself, as in “trust but verify”, is largely a non-issue. The automation is defined through its codebase, or alternatively, through its configuration settings. The configuration might have bugs or defects, but this is an entirely different proposition than having an element within the organization derailing directions given by the management.

These two visions are difficult to reconcile in practice, as their respective priorities for IT developments are very different. The reports and dashboards, as requested by the camp of the direct vision, are largely seen as a waste of time by the other camp. Not only would IT resources be wasted in setting up more reporting capabilities than strictly necessary, but later, employees will keep wasting time in endlessly revisiting those dashboards.

The camp of the indirect vision doesn’t categorically oppose reporting, but it doesn’t put nearly as much emphasis on the extent and the capabilities of those reports. From this perspective, the automation has been designed from the start to optimize metrics that mirror the KPIs themselves. For example, putting aside bugs and defects, given a stock on hand of 10 million euros, if the automation achieves an 88% service level while managers would have preferred a 90% service level, then there is no point in attempting to control further the automation. 88% is just what the automation achieves given 10 million euros worth of stock.

A superior technology for the automation might be able to reach this 90% service level under the same quota of working capital. However, it is not given that this superior technology can be engineered at all. This is fundamentally an open research problem that has nothing to do with control. Thus, monitoring the fine print of the automation is seen as a mostly pointless exercise as it doesn’t pave the way for any kind of tangible improvement of the automation itself. At best, it allows for an early detection of regression, but again, this can be achieved with much fewer indicators and reporting efforts than what a manager would typically expect in order to feel in control.

Conversely, the two-way integrations and all the sort of infrastructure level requirements of the camp of the indirect vision can be seen by the other camp as costly expenditures with no obvious returns on investment. Indeed, these spendings are largely instrumental rather than operational. Furthermore, those investments feel largely disconnected from the pressing imperative of the day-to-day operations. The camp of the direct vision doesn’t categorically reject integration either, or investing in the IT infrastructure in general, as these are needed for reporting purposes as well. However, it doesn’t put the same emphasis on the extent and the reliability of those integrations. Somewhat incomplete and unreliable integrations are tolerated as people are expected to remain in the loop. Nonsensical figures, as long as they are not too frequent, will be weeded out by people acting as filters against all kinds of IT nonsense.

In summary, while both the direct and indirect visions have strong expectations from the applicative landscape, their expectations are radically different and direct investments towards very different sorts of software.

In his famous book “The Goal”, published in 1984, Eliyahu Goldratt proposed a business philosophy that can be succinctly put as: “Any improvement made anywhere besides the bottleneck is an illusion”. As a testament to the popularity of the ideas proposed by Goldratt four decades ago, the appreciation of bottlenecks has become part of the mainstream business culture.

Nowadays, managers who have never heard of Goldratt may nonetheless instinctively adopt his framework known as the Theory of Constraints. The Theory of Constraints would benefit from a lecture of its own, but it boils down to a short series of steps: the constraints of the systems must be identified, we must decide how to exploit those constraints, we must subordinate other decisions to the exploitation of those constraints. Over time, we must elevate the constraints, and finally, as the constraints get elevated, we must go back to the starting point as another set of constraints has necessarily emerged as a new bottleneck of the system.

The direct vision is very much aligned with the way Goldratt envisioned the practice of his Theory of Constraints. The ‘rinse and repeat’ approach to work is given to the management. In supply chain terms, constraints would be the maximum amount of working capital, the maximum volume of stock that can be held in the storage facility, the minimum quality of service expected by the clients, and the maximum throughput of the warehouse to receive and expedite goods.

By way of anecdotal evidence, the emergencies that dominate the daily routine of many supply chain practitioners can be seen as a rapid shift in the place of the bottleneck. One day the bottleneck might be the lack of stock for a given product, the next day the bottleneck can be the lack of storage in the warehouse. In fact, alerts and exceptions, features that are widely found in supply chain software, could be loosely seen as automated detection systems of bottlenecks.

Conversely, the indirect vision is also concerned with bottlenecks, although it sees them in a completely different light. The indirect vision sees one bottleneck in particular as the king of bottlenecks, the one bottleneck that trumps all other bottlenecks: the capacity of the employees themselves to even apprehend bottlenecks. In the plot outlined in “The Goal” by Goldratt, the identification of the bottlenecks might be somewhat subtle, but their resolution requires not only a large amount of thinking, but also inventive thinking.

However, the plot of “The Goal” is set in a single plant producing a single product. The overall complexity would be considered extremely modest by the standards of our present digital age. Identifying bottlenecks when considering dozens of processes, hundreds of locations, and millions of SKUs – numbers commonly found in modern supply chains – is a completely different proposition compared to the single-product plant as outlined in “The Goal”.

The indirect vision sees the supply chain as a system that exceeds the capacity of the human mind to comprehend. It sees the capacity of the team to engineer automation that is capable of identifying bottlenecks as the supreme challenge to be addressed. Furthermore, unlike the manufacturing settings of “The Goal”, the resolution of the supply chain bottlenecks isn’t seen as something that requires truly inventive thinking. Resolution in supply chain boils down to allocating more or less resources, or upsizing or downsizing the infrastructure to transport, produce, or store the goods. Thus, if the automation is powerful enough to identify the bottleneck, then it’s a given that the automation is capable of addressing the bottleneck.

In summary, both the direct and the indirect visions acknowledge the importance of bottlenecks, but the two camps envision entirely different kinds of bottlenecks. The direct camp sees bottlenecks as an external phenomena, the manifestation of physical limitations within the flow of goods. The indirect camp sees its own inability at crafting the perfect automation, the one that would auto-resolve all bottlenecks, as the true bottleneck. The indirect camp sees bottlenecks as an internal phenomena, the manifestation of the intellectual limitations of those who supervise the flow of goods.

We have seen three sets of conflicting visions on knowledge, time, and work. This should have clarified what is being referred to as a vision in the context of this lecture. These visions are powerful and they suggest radically different paths to be taken to further develop a given supply chain. However, if two visions suggest diverging paths, it would be extremely surprising if those two paths would end up being equally beneficial or detrimental for the company. There is no apparent reason to think that all visions are equally valid for supply chain purposes.

Before tackling the question of the validity of these visions, let’s address their variety. In their strictest sense, the set of visions held by every person in the organization is as unique as the individuals themselves as minute variations can always be found. However, as Thomas Sowell in his book “A Conflict of Visions” demonstrates, almost the entire spectrum of political opinion held during the last three centuries in Western civilization is derived from a tiny few sharply distinctive visions, mostly revolving around the nature of man and its potential.

Based on my own casual observation over the last 15 years navigating supply chain circles, I firmly believe that a similar case can be made about supply chain. A tiny few sharply distinctive visions are backing the immense majority of the supply chain initiatives. When objections are voiced about the path taken by one of those initiatives, those objections are also voiced from the same tiny pool of visions.

The lack of variety among visions isn’t surprising. As stated at the very beginning of this lecture, visions are instinctive and simplistic in essence. People hardly ever contemplate the prospect of challenging their visions. When this happens, people tend to refer to the process as a “Road to Damascus” experience, which is both dramatic and startling. A much greater variety can be found downstream in the theories, processes, and techniques derived from those visions, as these are much more refined than the vision they originate from.

The relative homogeneity of the visions to be found in supply chain is of primal relevance because it implies that we are not facing the impossible prospect of proving or disproving the unique vision held by every single person. We are only concerned with the assessment of the validity of a small number of competing visions.

Nevertheless, assessing visions, even a small number of them, is difficult. In part, visions are not about what is – the facts laid bare – but rather about what should be. The facts themselves are largely seen through the lenses of the vision. Any failure can be attributed to a defective attempt rather than challenging the vision that birthed the attempt in the first place. For example, no matter how many times companies have failed to make any return on investment on their forecasting initiative, there seems to be an inexhaustible amount of faith that next time, the technology will have matured enough to finally deliver accurate forecasts. Similarly, no matter if every employee who has ever experienced an S&OP process from the inside describes it as a bureaucratic nightmare, companies appear to be still more than willing to set up their own S&OP processes, thinking that with them, it will be different. If the characteristics that Thomas Sowell has uncovered for visions in the realm of politics turn out to be shared with those in the realm of supply chain, then misguided visions should be expected to endure and persist for entire lifetimes, even when confronted with a mountain of contradictory evidence.

However, free markets are great filters. The market does not educate companies toward better visions; it just eliminates the companies that don’t dominantly embrace the correct ones. For example, many brick-and-mortar retailers came very late to e-commerce. They were late not due to any kind of technological barriers; they simply held a vision of retail that did not include the possibility of having their clients never enter any of their stores. Many of these retailers were sanctioned by bankruptcies, such as Toys R Us in 2017 and Bed Bath & Beyond in 2023.

A reasonable starting point to avoid this sort of debacle consists of identifying the dominant visions held within the company. Such a survey makes it possible to discuss the merits and demerits of those visions, as we did throughout this lecture.

In conclusion, visions are an intuition of causality. They act as a compass for the focus of the mind. Visions are also simplistic, and yet necessary. Visions shape how we intentionally engage complex systems, supply chain being a prime example of such systems. Barely any supply chain textbook or any supply chain software even acknowledges the visions that underlie them. Yet, far from being vision-agnostic or vision-free, both textbooks and software frequently are the epitome of specific visions of what supply chain should be according to their respective visions.

Those visions are potent, and they largely define how companies in turn approach their processes, their division of labor, the future, and planning in general, the roles and duties of their employees. Despite their importance, visions are rarely acknowledged, much less changed. For example, it is possible, as I did, to read hundreds of recent research papers on demand forecasting without encountering a single author who will question whether the technical perspective adopted in the paper is in itself actually suitable to apprehend the future.

Yet visions must be challenged. As we have seen in this lecture, the static vision, immensely popular in supply chain circles, does contradict what has been considered as basic economics for a century. This includes techniques like safety stocks and ABC analysis that are literally ubiquitous in the world of supply chain. Yet, if the history of science tells us anything, it is that widespread consensus doesn’t imply any kind of validity. The proposition that these supply chain techniques, ABC analysis and safety stocks, through their validity, would end up disproving the entire field of economics feels extremely improbable.

Supply chain is still fairly immature, both as a field of study and as a practice. As discussed previously in this series of lectures, it is not entirely clear whether supply chain even qualifies as a science yet. Whatever might be lacking in our present-day understanding of supply chain might go deep, vision deep. The sophistication, or the lack of sophistication, of the methods we have might be wholly irrelevant if it turned out that we are incorrectly framing the problems in the first place.

Now, I will be proceeding with the questions concerning this lecture. By the way, I will be pausing for a couple of months this series of lectures. I’ve realized that I need time to be able to put these lectures into written form. I’ve started working on a book and I expect to be able to consolidate all these elements into a coherent narrative that gathers all these insights. But now, I will actually proceed with the questions.

Question: Is there any way to automate and scale mundane knowledge without a rigorous knowledge system in a company? For example, is a small scale company unable to enact the quantitative approach you advocate?

The trick is that, by definition, mundane knowledge is what is not codified. If you find a way to codify whatever knowledge you have in the company, you effectively transform it into special knowledge. However, special knowledge is very costly, regardless of the size of the company. There is always an immense amount of mundane knowledge floating around because it would not be economically viable to try to codify, structure, and refine all of that. This is knowledge about the circumstances of time and place. A lot of this knowledge is transient. For example, it’s critical today to know the state of repair of a truck’s brakes, but once the brakes are repaired, this knowledge is no longer relevant.

So, it’s not really a problem of scale, but rather dealing with the balance between mundane and special knowledge. Every company, no matter the size, will have to deal with an immense body of mundane knowledge. You can’t hope to automate your way out of this issue.

Now, when it comes to the question of small-scale companies dealing with the quantitative approach that Lokad advocates, there has been an ongoing challenge over the last 15 years with the maturity of digital supply chains. Large companies have been digitalized for nearly four decades as far as their supply chains are concerned. Barcodes are not new. In small companies, this process only started two decades ago, so there is a 20-year time delta. Then there is the question of the level of integration of the application landscape. One characteristic of large companies is the availability of an IT department. As soon as you have an IT department, you have people who are paid to integrate the application landscape. Without this integration, you can’t consolidate the data to even start executing the quantitative supply chain as envisioned by Lokad.

That’s where the primary problem lies, in the lack of integration. But if you happen to have a very integrated application landscape, as is the case with some e-commerce companies, even very small companies can benefit from an approach like the one advocated by Lokad.

Question: Apparently, the majority of supply chain managers often justify their use of mainstream supply chain theory by claiming its simplicity, even though it somewhat inaccurately represents reality. Then they contrast it with some English superior, yet complex, technology. In such a debate, what would be your argument?

I don’t think that most supply chain managers would refer to mainstream supply chain theory in their daily practice. They are aware of it, and they’ve heard of concepts like optimal service level, perhaps during their university courses a few years back. But this is not about simplicity versus complexity. It’s really about how you approach problems. Do you approach them in ways that have grown organically within the company, or as distinct problem statements and solutions? These are completely different things.

Most managers, particularly those in positions of power in companies operating large supply chains, don’t view their roles and responsibilities as a set of problems and solutions. They see them more as ways of operation of the company, practices, habits, customs, and so on.

So, the gap is much wider than simply being aligned or not aligned with a theory. It’s literally a difference in how we approach the fundamental problem of what it means to improve a company. From a special knowledge perspective, improving means finding a better solution to a given problem. If your worldview doesn’t frame your position, and by extension, your division in the company, in terms of problems and solutions, then there is a mismatch in vision. It’s very difficult to reconcile that.

Indeed, there are points where, no matter which vision you have, it has to be a drastic simplification of the underlying reality. This is also true for the quantitative supply chain as approached by Lokad. The main difference is that we acknowledge that the effort going into modeling the supply chain is very much the bottleneck. This simplification is viewed as the primary constraint of the initiative.

However, it’s not about being under the illusion that what is being done is necessarily more advanced or more accurately reflecting reality than other approaches.

Thank you all, I think that will be it for today. See you next time.