00:07 Introduction

02:25 Selling homeware online

05:06 Competitive landscape

07:59 The story so far

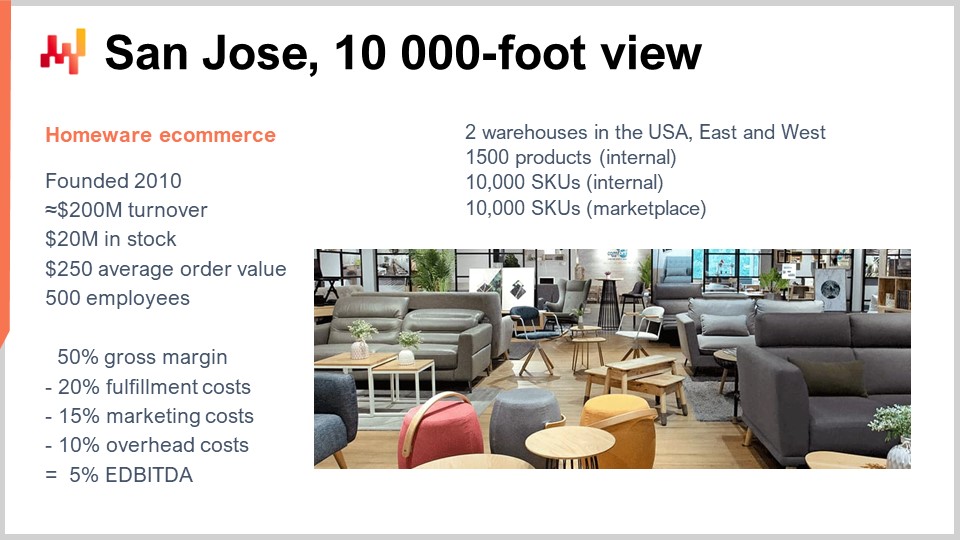

09:53 San Jose, 10000-foot view

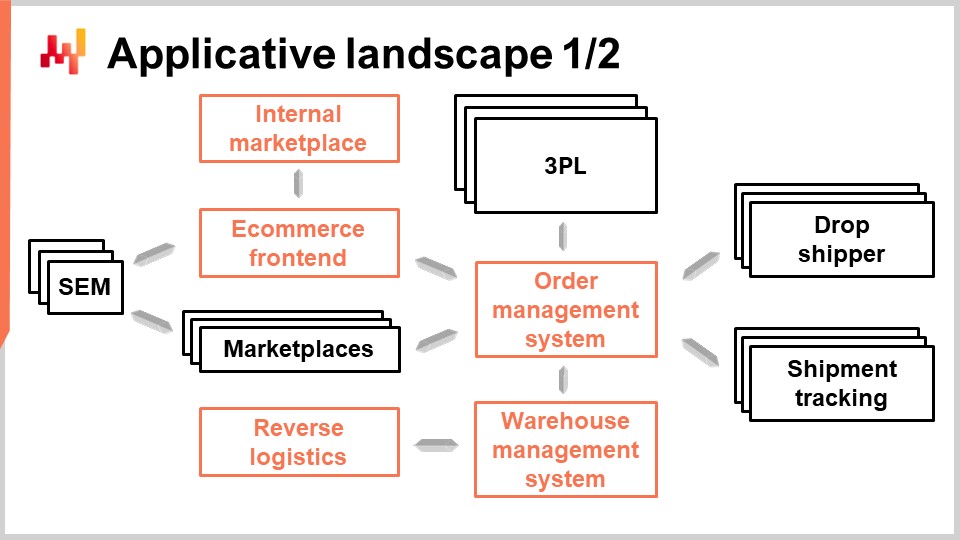

13:47 Applicative landscape 1/2

19:32 Applicative landscape 2/2

25:38 Home sweet home

26:06 Assorting

29:15 Purchasing

33:04 Allocating

36:09 Pricing

38:16 Selling

43:23 Promoting

49:24 Nuturing

52:20 Triaging

56:08 Conclusion

58:16 Upcoming lecture and audience questions

Description

San Jose is a fictitious ecommerce that distributes a variety of home furnishing and accessories. They operate their own online marketplace. Their private brand competes with external brands, both internally and externally. In order to remain competitive with larger and lower priced actors, San Jose’s supply chain attempts to deliver a high quality of service that takes many forms, well beyond the timely delivery of the goods ordered.

Full transcript

Welcome to this series of supply chain lectures. I am Joannes Vermorel, and today I will be presenting San Jose, a supply chain scenario that happens to be a homeware e-commerce. From afar, e-commerce appears to be a variant of mail order, which has been around since the 19th century. However, e-commerce is very different. By way of anecdotal evidence, by 2010, most mail-order companies had faded into complete irrelevance against their e-commerce rivals. E-commerce came with newer, better ways to market their offerings and serve their customers. From a supply chain perspective, e-commerce demonstrated a superior form of execution, at least compared to their former rivals, the mail order companies.

Today, we will be observing San Jose, a fictitious company that sells furniture and home accessories online. The goal of this lecture is to understand what supply chain is about in the specific case of e-commerce, or at least to have a very good look at one of those situations. This is the fourth supply chain scenario that we are introducing in this series of lectures. The motivation remains the same: we ultimately want to be able to assess whether a solution intended for a supply chain is going to be any good for this supply chain of interest. However, in order to do that, we must start with an in-depth assessment of the very problem that we are attempting to solve. Indeed, if the solution is not even solving the correct problem, there is very little chance that this solution can deliver anything good for this supply chain of interest.

Let’s start with a little bit of backstory. San Jose was founded in 2010 as a digital native. This is a second-generation e-commerce; they were founded with the ambition to sell furniture online, a segment that was very far from mainstream at the time. However, e-commerce was already mainstream; it’s just this furniture segment that was not. Thus, San Jose is not an e-commerce pioneer; they are just pioneers of the homeware segment online. By the time they were founded, there was already a series of very big pieces of tech that were readily available on the market: cloud computing, open-source e-commerce front-ends with tons of capabilities, and very powerful cloudified third-party logistics solutions. Thus, the initial focus of the team at San Jose was very much geared toward innovative designs for their furniture and toward digital marketing. The rest was considered as largely commoditized, if not clarified.

Now, the reality is that while the infrastructure investments of San Jose were very thin (and when I say infrastructure, I mean both logistics and IT), compared to the sort of investment that was involved with their brick-and-mortar competitors, as soon as San Jose got some initial traction with the market, they realized that they were playing a very complicated game. While the infrastructure could be commoditized to a large extent, all the supply chain decisions were not. San Jose was still fully responsible for every single supply chain decision, and they realized as they were gaining traction that actually all those parts that were largely commoditized were essentially the easy parts of the business, and they were still left with all the hard ones to manage internally.

San Jose is selling through its own website, and since the very beginning, the company has been engineered for growth, raising funds and pursuing a very aggressive growth strategy. Thus, very rapidly, San Jose expanded with additional channels. They started to sell on other marketplaces, and more recently, added two showrooms, one first in Los Angeles and then the second one in New York. Over time, they have been piling up channels, resulting in a very complex multi-channel setup. Despite a lot of growth during the last decade, San Jose remains a relatively small company in the vast homeware segment. In order to make their own website more attractive, they wanted to radically expand the offering found on the San Jose website. To do that, they opened their own marketplace, introducing other brands. Initially, these brands were very complementary to the San Jose brand, but over time, the scope of the marketplace increased, and now there are products from other brands that frontally compete with San Jose’s products. So, nowadays, the San Jose brand has to remain competitive on its own marketplace.

San Jose initially gained traction through innovative, catchy furniture design. However, as homeware became a mainstream segment for e-commerce, their designs were copied by competitors. Some competitors even directly sourced their products from the same suppliers. To remain competitive, San Jose had several options: one was to keep pushing more innovative designs, and another was to become very competitive at the supply chain game and deliver a superior form of supply chain execution. This supplements the innovation found in the design part of the business.

This lecture is part of a series of supply chain lectures, and this lecture is the fourth supply chain scenario introduced. In the third chapter, three other scenarios were introduced, and there was one supply chain scenario introduced right in the second chapter, right after introducing the methodology attached to supply chain scenarios. In the first chapter, I presented my views on supply chain both as a field of study and as a practice. In the second chapter, I introduced the meta-disease that I believe to be of prime relevance for supply chain. Some methodologies like case studies are incredibly weak against adversarial situations, and the situations found in supply chains are very much adversarial.

Supply chain scenarios should be thought of as a counterpoint to case studies. A supply chain scenario is a fictitious company, with an exclusive emphasis on the problem side of the equation. We completely postpone all the analysis of the potential solutions and only focus on the sort of problems that we’re facing and the nature of the challenge itself. Before being able to pretend to bring anything of value to a supply chain, we need to make sure that the solution is truly aligned with the problem as it is faced by the company itself, and that’s really what these supply chain scenarios are about.

San Jose is a fictitious homeware e-commerce; they sell furniture online, and a decade after being founded, they are now reaching $200 million in annual turnover. They are still growing fast, with double-digit annual growth, and they have $20 million worth of stock. This is particularly thin, considering that most of the suppliers are overseas and the lead times are typically longer than 10 weeks. As part of their practice to keep their working capital requirements very low, they actually start selling the goods as soon as they are in the container. The goal is to have all the contents of the containers already sold by the time they land in the US ports, which can dramatically lower their working capital requirements.

They have a fairly comfortable gross margin at 50%, but there are also quite a lot of costs. There are 20% fulfillment costs, which include carrying costs, warehousing costs, delivery costs, and transaction processing fees. They have 15% marketing costs, which represent mostly digital advertising costs. Finally, they have a 10% overhead cost, which includes the white-collar jobs and some IT infrastructure costs. The supply chain costs are spread between operations, which are part of fulfillment costs, and the white-collar jobs that are part of overhead costs. Overall, what is left is a 5% EBITDA, which is quite nice considering the company is growing very fast.

From a supply chain perspective, there is potential for improvement. About 5% of cost reduction on fulfillment costs could be achieved through various supply chain optimizations, bringing the number down to 15%. On the overhead costs, they might be able to shrink the cost by 5% as well if they can achieve a high degree of automation. Many of the white-collar jobs are people who have to deal with replenishment, pricing, and other mundane decisions that represent a significant overhead. What is at stake is literally tripling their EBITDA through supply chain optimization by compressing both the operational costs and the overhead costs.

San Jose went for a digital strategy from day one and has been growing over time. Understanding the applicative landscape is absolutely fundamental. It is not possible to directly observe a supply chain; the only thing you can really observe are the electronic records collected from the applicative landscape. To be good at supply chain management, you need to embrace the applicative landscape, which gives you the perception of the supply chain itself.

San Jose started with an e-commerce frontend, the website where they can sell their own products. This was obviously the first piece they needed to start selling. However, as soon as they added one extra marketplace, they had a problem: they had to synchronize the stocks and prices. As soon as you have a second sales channel, both channels need to be aware of what is being sold by the other channel. This is because the availability of the products and the prices can impact the sales on both channels.

Indeed, in the end, you have only one stock, even if this stock happens to be moving across the ocean because you’re selling items that are currently sitting in a container. All your channels are consuming the same stock, so you need to have some kind of synchronization so that all your channels can see the same stock. Whenever you adjust a price, you want to make sure that there are no mistakes and that you have consistent prices across all the channels. Otherwise, you give an incentive to your clients to take advantage of pricing discrepancies by switching between channels. To accomplish this basic synchronization of stocks and prices, you need a piece of software, and this is exactly what the Order Management System (OMS) is for.

San Jose introduced the OMS as the second piece in their applicative landscape to handle this synchronization. The OMS is a fairly capable piece of enterprise software, and it is the closest thing that San Jose has to an ERP. It essentially plays the role of an ERP in the applicative landscape. As San Jose started to grow, they set up their first warehouse on the West Coast and later added a second one on the East Coast. As they began to manage their own shipments directly from their warehouses, they had to set up another piece of software, a Warehouse Management System (WMS), to handle the complexity involved with managing and running a modern warehouse.

As the business expanded, they experienced more and more returns. Returns in the homeware segment are very expensive, both financially and in terms of customer loyalty. A major module was added to the WMS, which was dedicated to reverse logistics. As they expanded, they had to integrate carriers and shippers with the OMS. By having tight integration with carriers and shippers, they could provide their customers with a clear view of the status of their pending orders. To do this, they needed to connect all these systems, so that information could flow back from carriers and shippers into the e-commerce frontend for display and customer access.

Third-party logistics (3PLs) had to be integrated, and later on, as the e-commerce frontend expanded with the marketplace, they had to integrate an entire extra subsystem to manage third-party brands. Initially, the e-commerce marketplace was only intended to manage products operated by San Jose themselves, not by third-party brands, which created an extra layer of complications and IT entanglements.

However, the e-commerce landscape is even more complex than that. There are even more elements to consider, such as merchandising. When people search on the website, they perform queries, and you want to decide what to display. There is plenty of complexity involved in determining the product rankings to display. It’s not just a search engine; it’s a merchandising system, which means that San Jose is selling spots in their search engine to their competitors or competing brands present on the San Jose marketplace. This same system also exists with other marketplaces, where San Jose buys advertising, referred to as search engine marketing (SEM). Essentially, you are buying prime real estate on the channel, and San Jose does this on other marketplaces as well. It’s a complicated game because giving too much space to competitors on your own platform might devalue your own brand.

Then, you have the Product Information Management (PIM) system, which contains all the technical information about the products beyond what is displayed on the website. For example, the PIM typically contains the bill of materials for bundles and assemblies, and many products have parts or modules in common. In homeware, the PIM holds all this information. If San Jose had more complex products involving electronics, they might use a Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) system, but with their relatively basic products, a PIM is sufficient.

They also have a Point of Sale (POS) system, used for their two showrooms. Although these showrooms represent only a small fraction of the annual turnover, for a few product references, they are the dominant channels. Additionally, there is the Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system, used mostly by the marketing team to carry out direct marketing campaigns, such as sending newsletters. The CRM can direct a lot of inbound traffic, which has a significant effect on the influx of demand. The supply chain must be prepared to serve these fluctuations in demand.

Finally, there is competitive intelligence. The competitive intelligence service gathers prices from a series of well-identified competitors. It’s a bit tricky because there is usually no one-to-one matching between the products sold by San Jose and the products sold by its competitors. Nevertheless, competitive intelligence is relevant to explain significant swings in demand, which might otherwise be hard to account for, such as competitors running massive promotions that temporarily capture a large portion of online demand. This effect is intensified by the fact that everyone is playing on the same marketplaces, and these price moves occur simultaneously across all marketplaces.

Now, what we see here is that we already have a dozen apps, and all these apps contain information that is very relevant for supply chain purposes. Most of these apps contain mundane data, but as we will see, most of the supply chain challenges involve accessing this mundane data. I didn’t review the applicative landscape for the other supply chain cases that we have seen so far, mainly because the landscape tends to grow and become more complex and messier over time. Here, despite appearing complicated, it is still a lean setup for a relatively fresh company that is just a decade old. If we were to look at a company that is four or five decades old, you could have three or four times more apps in your landscape, and each of these apps holds some very valuable data.

As we’ve surveyed the applicative landscape, let’s now review the supply chain decisions that must be taken daily by San Jose. Being properly informed is key to making better decisions, and the bulk of the relevant data will be found in these systems.

The first problem we have to address is the assorting. When do we decide that a product should enter the assorting of San Jose? The strategic orientations on design and quality are probably mostly marketing concerns, not supply chain concerns. However, these criteria may or may not restrict the supply chain options available, so it’s not just a marketing problem; it’s also a supply chain problem.

Once a design is picked, there is the question of choosing the variants. This is a problem we’ve already seen with our first case study, a fashion brand in Paris. Once you pick a design, you have dozens of variants to consider, looking at different dimensions, colors, and materials. San Jose, compared to the Paris case study, has more expensive designs and even more possible variants due to the nature of homeware. For example, you can have half a dozen dimensions at play when looking at a complex piece of furniture. The more variants you have, the more supply chain complexity you will bear. As we’ll see later, there are nonlinear constraints that complicate your choice of variants. For instance, when you have minimum order quantities (MOQs), if you go for too many variants, it becomes very difficult to reach your MOQs.

This problem of assorting is, in my opinion, very much a supply chain problem, or at least a problem that needs to be solved jointly by marketing and supply chain. When we start projecting demand, we see that every single extra design introduced as part of the assorting competes with all the other products that already exist. There is no such thing as a demand forecast for one product; the demand forecast for every single product is dependent on the assorting as a whole.

For every single product and variant, every single day, San Jose has to decide how much to buy. San Jose predominantly imports from overseas suppliers based in Asia. Due to the lead time, there is also a significant amount of retro planning involved to properly account for seasonality, considering that things will take time to arrive. Typically, there are at least 10 weeks of lead time for the vast majority of products, and it can go up to six months for more complex products.

Purchasing comes with all the classic constraints. There are minimum order quantities (MOQs) that can be expressed per product, product type, design, type of material, color, or supplier. There are also minimum order volumes (MOVs) expressed in dollars, representing the minimal quantities needed once expressed in dollars. Once a purchase order reaches its target quantities, there is typically an option on the table to decide what the desired shipment timeline should be. The supplier can either produce everything, wait until the entire production batch is complete, and then ship everything, or ship products as production progresses. The teams at San Jose must plan the exact schedule of the desirable shipments associated with every single purchase order they make.

Additionally, the teams of San Jose want to minimize transportation costs. They will favor full containers to compress transportation costs whenever possible. For certain products that have a favorable dollar-to-kilogram ratio, such as lighting products with LEDs, air shipments are also of interest. As a result, there is a mix of transportation modes at play.

Not buying at all is also an option. San Jose can work with local suppliers who are capable of drop shipping, where the supplier is fully responsible for the ownership of the stock and servicing the client. However, this can’t be the only option for the business, as it raises the question of San Jose’s added value in this segment. Drop shipping is typically favorable for bulky, oversized products like sofas or bathtubs.

San Jose has two warehouses, one on the West Coast and another on the East Coast. When making purchases, they must decide how to distribute the quantities between these two warehouses. While it is possible to rebalance the stock between the two, it is better if there is minimal rebalancing happening over time. In terms of stock allocation, San Jose must first decide the right quantities for each warehouse. As soon as quantities are received in the warehouse, San Jose has to decide how much stock will be kept inside their warehouse and how much stock will be directly sent toward third-party logistical providers (3PLs). These 3PLs, which typically back very large online marketplaces, are more efficient, especially for small items, in terms of time to delivery for the end customers. They are more agile and efficient, thus it’s better for those types of products to leverage the 3PLs because they outcompete what San Jose can do internally with their own shipment capabilities.

However, these 3PLs come with a catch, as they typically have very aggressive long-term storage fees. From time to time, San Jose has to take back stock from the 3PLs back into their warehouses to avoid these costly long-term storage fees. Allocation also comes with the extra problem of multi-order, multi-item customer orders. Customers typically order multiple items at once, and San Jose has to decide whether they want to send the items as soon as they are ready or wait until the entire order is ready. Fragmenting the shipment can be very expensive, and fulfillment cost is already one of San Jose’s biggest spending areas. Thus, optimizing shipment has a significant impact on the bottom line.

There is a price point to be chosen for every single product, and pricing is very much a supply chain problem because it has a significant impact on demand, which in turn affects the quality of service depending on the available supply. Reducing the price increases demand, and price optimization is made more complex by the presence of flagship or iconic products. San Jose gained traction through innovative, catchy designs – their iconic products – which drive a lot of sales volume through the accessories that come along with those products. People buy the iconic products and then purchase many accessories with them, which typically have superior margins.

This creates a challenging situation where it could be tempting to lower the price of iconic products to increase volumes. However, doing so risks devaluing the brand itself, creating a trade-off between the long-term interests of San Jose as a brand and the short-term cash flow interests of San Jose as a company. This trade-off must be orchestrated with pricing, which, as we have seen, is something that lies between marketing and supply chain. The factors at play are both the value of the brand and the company’s specific growth targets for a given quarter.

As we have seen, San Jose holds remarkably little inventory compared to its turnover. Lead times are long, at least 10 weeks for their overseas suppliers, predominantly in Asia. In order to lower its working capital requirements, San Jose starts selling products as soon as they are secured in transit in a container. The goal is ideally to have the containers fully sold by the time they reach the ports. Depending on the conditions negotiated with the suppliers, San Jose might end up selling the product even before they have to pay for it to their supplier, which is a very advantageous position. This is how they have been able to grow while maintaining very low working capital requirements. However, in order to do this, San Jose needs to carefully assess the estimated time of arrival (ETA) of every single product in transit.

As a rule of thumb in terms of willingness to wait, the more expensive the product, the more willing customers are to wait. For example, if a customer is buying a $3,000 sofa, they might be willing to wait 10 weeks, but if they are buying a $50 table lamp, they may want it within two or three days. Thus, there is a question for every single product: when do you start selling, and when do you stop selling? You can start selling as soon as you have a reliable ETA, but you also have to decide when to stop selling. If it takes too long, people might cancel their orders even if the expected wait time was initially communicated.

When considering quality of service, the usual notion of stockout is inadequate to reflect what is happening at San Jose. It’s better to think in terms of quality of service and staying true to the promise initially made, while remaining within reasonable boundaries that can fluctuate depending on the product in question. The interesting thing is that San Jose can invest in bigger commitments toward their stock, not necessarily holding more inventory, to increase availability and compress delays. By doing so, they can increase demand. However, this is not the only way to increase demand. The other canonical way is to invest in new innovative designs, which create new demand.

Investing in compressing delays comes with diminishing returns; there is a point where investing more in stock will not proportionally inflate demand. Thus, from the company’s perspective, there is a trade-off between the investment to be made in stocks and the investments to be made in the creation of new designs. The optimization of San Jose’s business consists of constantly making trade-offs between these two types of decisions, even though these decisions are typically assigned to very different divisions: supply chain and marketing.

Promoting the product starts by deciding how to put forward the products. For San Jose, because they are an e-commerce business, the starting point to promote anything is their homepage. If they put something on display on their homepage, which has massive traffic, whatever product is put on their page is going to have a massive surge of demand.

Now some could say that deciding what is on the homepage of San Jose is a pure marketing decision, but not so much. Obviously, you want to make sure that if you put stuff on display on the homepage, you have the possibility to serve all the demand that you’re about to generate while putting those products so prominently on display. Conversely, if you have products that are running the risk of incurring overstocks (and remember that San Jose has a very tight notion of overstocks because from their perspective as soon as a container lands in the US while not being fully sold, it is the tipping point to start counting as overstock from their playbook. So if you have products where you feel that you’re about to be in overstock, you can put them more prominently on the front page. And obviously, you can repeat this sort of line of thinking for every single subsection on the website.

You can even do that with the search results. Search results are not just about whatever products most closely match the queries that you’ve entered on the website. You can decide to slightly tune the results of the website to promote and rank slightly higher all the products that are slightly overstocked and conversely, slightly derank the products that are already severely backlogged. Again, there is no such thing as really stuck out products here; it’s more like products that have already quite a significant backlog and that’s not the sort of product that you really want to promote.

And also, with the search results, we have to deal with the ranking. So we have the rankings for the static sections of the website and we have the rankings for the search results. And all of that are as many decisions exactly what are the ranks. And in addition, we have seen that the search engine and the search results are not just plain search results; there is some advertising going on. So some slots are actually sold to other brands that are part of the marketplace.

And there is the question of what is the price point at which do you want to sell a slot? You see, because at some point it might be preferable if competing brands are not paying enough, it might be preferable not to put them permanently forward. This might be some sort of auction but nonetheless there is some kind of reserve price under which San Jose should decide that it’s better off to just display their own products. And this has to be adjusted and again it very much depends on the sort of query. The price per click is going to be widely different depending on whether you’re talking of a $10 accessory or whether you’re talking of a $3,000 sofa that I was describing before.

Then more classically, we have said that promotion is about what do you put forward, but obviously there is also the matter of discounts. By reducing the price, you can boost sales and that’s a way also to mitigate overstock or even slow-moving stocks. Unlike fashion stores, unlike the Celta situation we have seen with Paris the fashion brand Persona, San Jose doesn’t have really a constraint of making room for the new incoming collection. This is an online catalog so there is very little hard constraint on whether a product really needs to go to make room for new arrivals.

Nonetheless, carrying costs can accumulate quickly and by making sure that products are rapidly liquidated, you make a lot of room for novelty so that your catalog doesn’t get entirely cluttered by underperforming products. And thus discounts are a way to achieve that. However, as we have seen with Paris this fashion brand Persona already, whenever you offer a discount to your customers beware there is a second-order effect which is not only do you have to pay for the reduction of gross margin due to the discount being present, but you also create expectations among your customer base and those customers will be expecting discounts in the future if they do benefit from discounts now. So this has a long-term impact on the brand and you want to make sure that whatever you’re doing in terms of discounts and potentially flash sales doesn’t devalue your brand.

Supply chain questions for San Jose were mostly driven by the product. We were thinking of supply chain through the lens of what is happening at the product level, such as what sort of quantity should be purchased and what sort of price point is needed. In supply chain management, there is a strong tendency to approach many problems through the lens of the products. In terms of data analytics, this leads to intuitive solutions where each product can have its own time series, which is relatively straightforward to execute. However, this product-centric perspective and time series-centric analytics can be blind to many angles.

For example, some challenges are best approached at another level of granularity. Sometimes, taking the perspective of the customer is more relevant. San Jose can predict if a pending customer order is going to be delivered later than originally promised. They are not yet late, but they know that most likely they will not make it on time. So, what can they do about it? They can proactively contact the customer and give a voucher that could be redeemed on a later order to make amends for the pending problem, potentially reducing the rate of late cancellations. The degree of generosity with the voucher is probably more of a marketing problem, but the decision of giving away a voucher for late delivery relies on the accurate assessment of a probable ETA breach, which is a supply chain matter. As we can see, there are many situations where supply chain assessment can be done at granularities that are not just the products.

San Jose is a relatively small company compared to its competitors, and it must remain efficient, especially supply chain-wise. There are many inefficiencies that do not exist within San Jose but exist outside the company itself or at its boundaries. Let’s have a look at the suppliers first. San Jose is too small to internalize the production of the goods they sell, so they rely on third-party suppliers. Some of these suppliers might be unreliable, unable to produce the right quantities, or produce on time. Others might have quality issues, and when San Jose receives the goods, they realize that the delivered products do not meet the standards of quality expected for their brand. The supply chain practice at San Jose must connect all these dots and filter out unreliable suppliers from their ecosystem; otherwise, they would damage the brand.

Similar problems occur for vendors. As I mentioned earlier, San Jose started to have a marketplace on its website. However, if a vendor on the marketplace underperforms, it’s not just the vendor that is penalized, but the marketplace as a whole. San Jose must be selective and careful about the vendors they keep on their platform. The decision to retain or remove a vendor is driven by supply chain indicators.

Even customers can be problematic to some extent. A customer who abuses the late cancellation policy might incur severe costs for San Jose. While it’s not necessarily ethical or legal to ban a customer outright, it is still wise not to engage further with a customer known to be unprofitable for the company. For instance, if a customer frequently generates late cancellations and costs, it’s better not to try to interact more with them through direct marketing actions. Interacting with a customer is a marketing action, but the decision not to do so will be based on supply chain indicators.

In conclusion, most of the challenges faced by San Jose are an entanglement of marketing, supply chain, and IT concerns. Even supposedly hard physical constraints, such as lead times for overseas suppliers, are much softer than they seem. San Jose can play with resource constraints in many ways, as illustrated by the idea of having customers buy goods while the products are still in transit. The applicative landscape at San Jose provides enormous flexibility and capabilities. However, these capabilities must be leveraged intelligently to benefit the business.

In this series of lectures, I define supply chain broadly as the mastery of optionality when dealing with the flow of physical goods. While San Jose can rely extensively on commoditized, external solutions for its logistics and IT infrastructure, all decisions remain in their hands. In a way, San Jose is even more supply chain-driven due to the fact that they have more options available on the table at any point in time. They are more supply chain-driven than their brick-and-mortar rivals, who operate under much tighter logistical constraints.

Let’s have a look at the questions. My team reports that there are no questions. It was a fairly specialized topic, so I believe that will be all for today. In three weeks, I will be discussing another topic, which will be language and compilers for supply chain. It will be a very technical lecture but an important one. It will be on the same day of the week, Wednesday, at the same time of the day, 3 p.m. Paris time. See you next time.