00:51 Introduction

02:14 Novelty

03:32 The story so far

05:16 The short definition (recap)

07:00 Crafting a supply chain persona (recap)

08:50 Paris, 10 000-foot view

16:18 Range planning 1/3

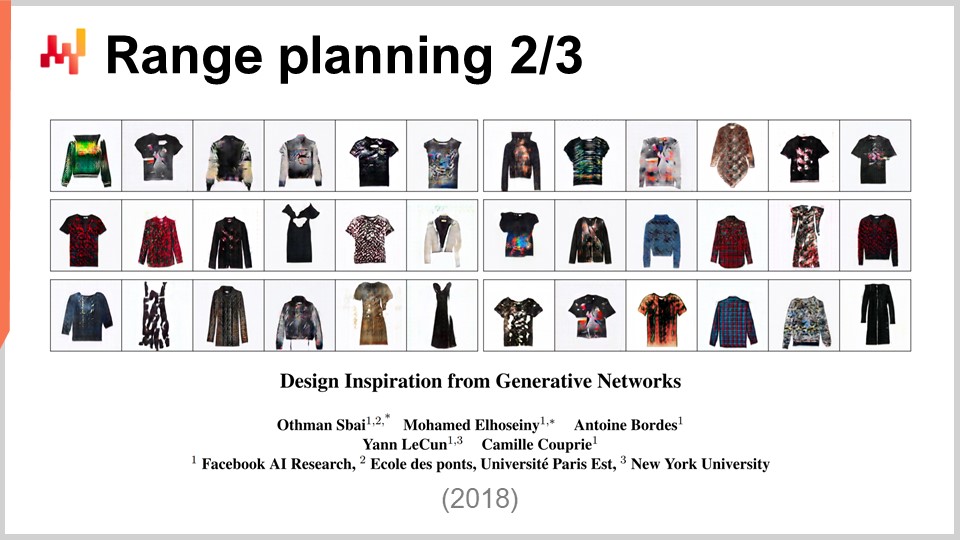

19:25 Range planning 2/3

21:18 Range planning 3/3

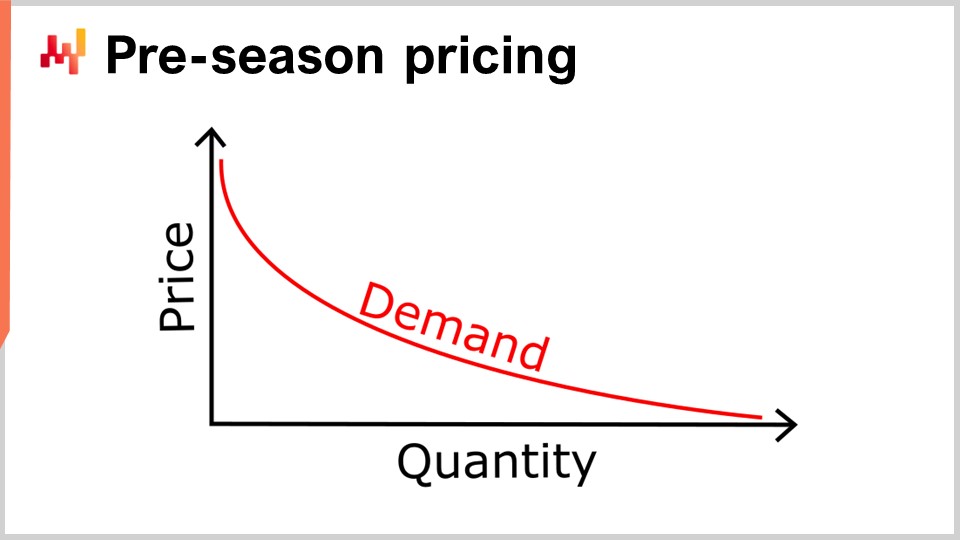

25:08 Pre-season pricing

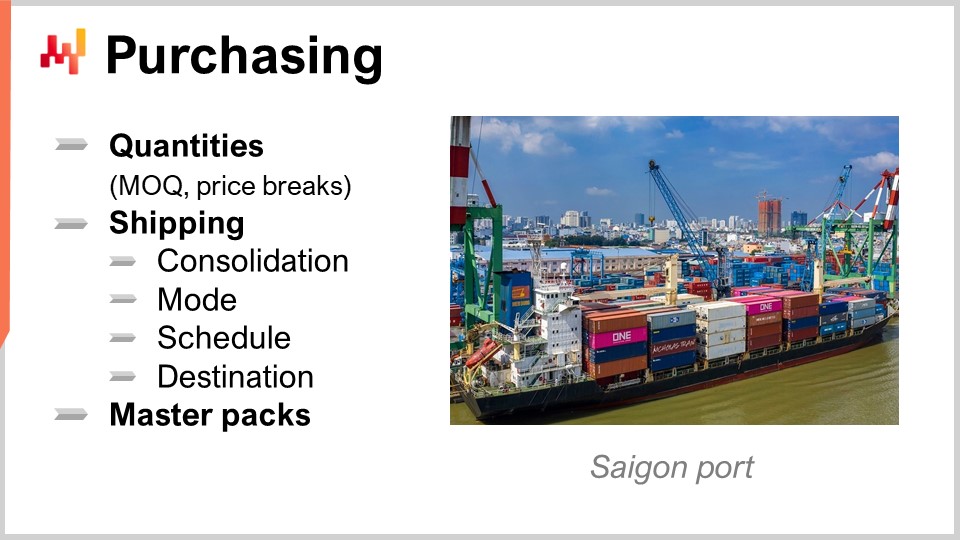

29:27 Purchasing

38:12 Inbound distribution center

41:36 Store “initial” push

47:51 Store “routine” push

56:02 In-season pricing

01:00:59 Other elements - limitations of this Personae

01:04:16 Conclusion

01:06:42 Upcoming lecture and audience questions

Description

Paris is a fictitious European fashion brand operating a large retail network. The brand targets women and positions itself as being relatively affordable. While the design line is relatively classic and sober, the main business driver has always been novelty. Multiple collections per year are used to push waves of new products. Pushing the right product, at the right time, at the right price and with the right stock quantity is one of the core challenges

Full transcript

Hi everyone, welcome to this series of supply chain lectures. I am Joannes Vermorel, CEO and founder of Lokad, and today I will be presenting “Paris Supply Chain Personae”. For those of you who are watching the lecture live, you can ask questions at any point in time via the YouTube chat. I will not be reading the chat during the lecture, however, at the very end of the lecture, I will get back to the chat and do my best to answer the questions that I find there.

The topic of interest for us today is supply chain and fashion, or more precisely, what can supply chain do for fashion. Whenever I open supply chain books, I usually find something like five lines per paragraph to actually discuss the specific challenges that we face. Then, the book goes on to discuss the solution or, I would say, an ingredient of the solution. The solution might be something like time series forecasting or open to buy or snop. But really, when we have this sort of imbalance between the problem side of things and the solution side of things, I reflect about the imbalance and whether we have a real adequacy of the solutions that are being proposed with regard to the problem.

That will be the main point of the personnel that we’ll discuss today. Paris, a women’s fashion brand, will be covered in great detail in the following. The problem will be to analyze the sort of problems that can be found in fashion.

The challenge for me is to make a presentation that makes sense. If I just list a gigantic catalog of all the problems that are faced by fashion companies, I will probably end up with something that is barely making sense.

So, the way I’ve decided to go through this exercise is to take the angle of novelty. Fashion at its core is driven by novelty, and fashion itself is a subtle annual phenomenon where it’s always kind of the same but always kind of different as well. The point of this lecture will not be a lecture about fashion itself and its dynamics, but rather on how this dynamics articulates with the supply chain changes that we are facing.

The way I propose to journey through all the series of problems faced by many supply chain companies is to go through the life cycle of the product itself. This is exactly what we’ll do to journey through the life cycle of the products that are designed, produced, and so on by Paris, this fictitious company.

So far, this lecture is the second lecture of the second chapter in this world series of supply chain lectures. The world plan is available online for those who are interested. We have already concluded the first chapter, which was a prologue where I gave my general views about supply chain, both as a field of study and as a practice. What we have seen in this first chapter is that the improvement of supply chain is essentially a wicked problem, as opposed to tame problems. Methodology is really of high importance, and as a rule of thumb, most naive methodologies just fail when it comes to supply chain, due to its wicked nature. In the previous lecture, we discussed supply chain from a qualitative angle, and I introduced the notion of supply chain personas. If you haven’t seen the first lecture, today’s lecture will make more sense once you’ve watched it. However, I will provide a brief recap to ensure you’re not completely lost if you’re watching this lecture without having seen the previous one. In this second lecture, we will delve into the specifics of supply chain management in the fashion industry.

To recap, I proposed defining supply chain as the mastery of optionality in the presence of variability when managing the flows of physical goods. In what follows, we’ll use this definition to establish what constitutes a relevant supply chain problem. By optionality, I refer to well-defined decisions that are narrow in scope. For example, a decision to move one unit of a given product from a distribution center to a store today is clearly a well-defined decision with a narrow scope. On the other end of the spectrum, a decision to change the company logo would have many ramifications and would require significant creativity, challenging the visual identity of the brand.

The idea of the supply chain persona is to convey supply chain knowledge in a format that ideally possesses scientific-like attributes. A persona represents a fictitious company, with two key aspects: it is fictitious out of necessity to avoid the problems associated with discussing real companies and their specific issues; and it focuses on the problem side of things, rather than the solutions, to avoid conflicts of interest that may arise when advocating for one solution over another. By focusing on the problem, we can eliminate conflicts of interest and concentrate on the most relevant aspects of the supply chain.

In this lecture, we will examine the supply chain persona for “Paris,” a fictitious women’s fashion brand that operates a fairly large retail network. On this slide, I have gathered a series of KPIs to give you a sense of the company we are discussing. Keep in mind that all of this is fictitious and made up. I’ll give you a few seconds to read the slide and capture the essence of this company.

Let’s discuss these numbers and why I picked them in particular. The €1 billion annual turnover is characteristic of the scale that represents brands found most routinely in malls or shopping centers in Europe and North America. It also characterizes a certain set of problems. If we were looking at companies with €10 billion per year, we would probably be looking at worldwide giants, which are frequently quite vertically integrated, unlike Paris. Conversely, if we were looking at a company with €100 million turnover, it would likely be a specialist with a specific angle to attack the market, steering away from the mainstream fashion brand we’re trying to capture with this persona.

The 3% EBITDA reflects the reality that fashion is a tough market with relatively thin margins. This is interesting for us because it demonstrates that supply chain management matters significantly. For instance, if you can increase EBITDA by just 1%, you’ve increased the profit by one-third. The 50% initial gross margin on catalog price and 20% discount are relatively representative of what is observed in this market. Products have a sizeable margin when initially sold, but the company is not as profitable due to end-of-season sales and substantial discounts given away at the end of every collection.

I assume that e-commerce is present, accounting for 10% of the volume. The e-commerce store is the biggest store in the network, but this persona is not about an e-commerce company. If we were to talk about an e-commerce company, that would be another persona. We assume that the company emerged in the late 20th century and was not a digital native. E-commerce is very much an afterthought that emerged later and has grown rapidly, but it is still not dominant. The main channel consists of the 1,000 stores, which is dominant in this scenario. If you have 1,000 stores for one billion euros of turnover, the average store’s annual revenue is one million euros. These stores are boutiques, not superstores, which is common in the world of mid-market fashion.

The median store likely has a turnover of only half a million euros per year. In a company like Paris, you typically find power stores that are small in terms of square meters but are exceedingly well-placed. These stores may be located in train stations or busy areas of high-profile cities. On the other end of the spectrum, there are suburban stores that are larger in terms of square meters but have lower sales volumes. Interestingly, the stores that sell the most are also the smallest. We’ll come back to this dynamic later.

The company has two distribution centers, one in France and one in Germany, and operates in six countries. Although relatively concentrated in terms of geography, the company services a territory spanning a thousand kilometers. One distribution center serves several hundred stores, a ratio commonly found in the fashion industry but different from what you’d find in hypermarkets, for example.

In terms of offerings, we’re looking at 1,000 distinct products at any point in time served by the network. It’s essential to differentiate between products and variants, which include size and color combinations. When you go from products to variants, you inflate the number of references by an order of magnitude. Assuming there are four collections per year in women’s fashion, about two-thirds of the products are new at every collection, with one-third being continuations of previous offerings. If we were discussing men’s fashion, the ratio of novelty would be slightly lower. The majority of products for every collection have never been sold before, even though fashion products are always variations of some kind with regard to what was done previously.

Let’s start the journey of the product life cycle with range planning. At the very start of a collection, there may be a list of stylistic ideas or styles. When I say 50 styles, it’s not an exact number, but rather the idea that we have a few dozen design ideas, not hundreds. These ideas will make up the theme of the collection.

Based on these 50 or so stylistic ideas, they will be gradually inflated to create the 10,000 variants that we have at the end when building the whole assortment. The proposition I have for you is that the transition from those 50 stylistic ideas to the 10,000 variants representing the assortment is, in large part, a supply chain problem. I don’t want to deny the fact that there might be a great deal of design skill needed to derive a product from a stylistic idea. What I’m saying is that there is clearly a point where the problem of range planning becomes a supply chain problem.

For example, at the end of the process, we have to decide on all the sizes we will want to have. We might decide that for every single product, we have the whole range of sizes, or maybe not. Maybe some products don’t justify having seven different sizes and will only have three. There are many options on the table, and the supply chain is about mastering this optionality. Deciding the fine print of options is not just a matter of sheer creativity; you have to fit your market and balance supply and demand.

Similar things could be said about colors. Design will have a lot to say about the choice of colors, but in the end, we have to decide for every single product whether we have one color, two colors, or twenty. It’s not just a matter of design; there is the question of balancing supply and demand.

As a rule, we want to focus on the problem side of things, but I will make a tiny jump to a solution by quoting a recent research paper from Facebook. The paper discusses design inspiration from generative networks. The team at Facebook built a software program capable of dynamically generating new designs based on a dataset of fashion pictures. That’s very interesting because, if we go back to the idea of range planning and starting with stylistic ideas, we see that it’s not science fiction to think that a great deal of work can be done in ways that are profoundly automated and optimized, even going back to the actual generation of new styles. In particular, there are other publications that I won’t discuss today, explaining how successes have been achieved in doing some style transfer. It’s possible to take a t-shirt, identify the sort of style in terms of pattern, and then transfer it automatically and apply the same style to, let’s say, a dress. This is fascinating because suddenly, things that looked as if they belonged only to the realm of pure design and creativity become options that can be exploited at will with the right infrastructure in place, such as software to do this work for us.

The point I wanted to discuss is that there is a good portion of range planning work that should be considered very much as a supply chain problem because it’s just a matter of exploiting options on the table. Now, what are the drivers that define a good or bad assortment? We have to look at the drivers, and the first driver is extensive coverage. Every single new product added to the assortment provides the opportunity to please an extra fraction of clientele that can be captured via an extended assortment. So, a bigger assortment intuitively captures a bigger portion of the demand.

However, we also have an effect of diminishing returns because, for every single product introduced, there will be some kind of cannibalization taking place. For example, if you introduce one black dress, there will likely be some demand for it. But if you introduce a second black dress with a slightly different cut, the question is, will we double the demand? Probably not. We’ll probably get a little more demand, but many clients walking into a store will hesitate between the two and pick only one of them, not both. So, the assortment is a compromise, a trade-off between capturing more demand with a bigger assortment and dealing with cannibalization or substitution that takes place.

Every time we inflate the size of the assortment, we create extra complexities. For every single product added to the assortment, we’ll have to design and finalize the product, create nice digital pictures for e-commerce display, and gather all the necessary information. We’ll need to have the product sourced, produced, and managed as a separate reference. There might be plenty of processes needed just to support every single product added. There is some economy of scale, but as we are looking at something like a thousand-plus products, we can expect to rapidly exhaust those economies of scale. Every single product added will incur linear extra costs while providing diminishing returns. However, there are also plenty of nonlinearities that we will explore later. By nonlinearities, I mean, for example, MOQs (Minimum Order Quantities). The larger the assortment, the more difficult it will be to purchase large quantities for every single product, making it challenging to reach those MOQs. It’s always possible to reach the MOQ, but if the assortment is extensive, we will be mechanically at risk of ending up with a lot of excess stock because we had to order more than what was needed to satisfy those MOQ constraints. We have plenty of drivers that constrain what we can do with regard to assortment.

When building an assortment, we anticipate some kind of demand for those products. There is a self-prophetic effect at play here. It’s because we see potential demand that we create, design, and produce a product, which will then generate demand. There are strong self-prophetic effects, such as price, where a lower price can lead to more demand, allowing for larger quantities to be produced and leveraging economies of scale at the production level. Due to economies of scale, you can produce at a cheaper price and, in turn, generate more demand. The same thing goes in the opposite direction.

We have this tension within the assortment. The bigger the assortment, the more we can cover internal demand, making it more appealing. However, the larger the assortment, the smaller the quantities for every single product, and thus, the fewer economies of scale we will enjoy when trying to produce these products. This is the law of supply and demand – Economics 101.

A decade ago, I witnessed a client of Lokad, a fashion e-commerce, conducting tests in this area. The question being tested was, what happens when the price goes to zero? Will the demand go to infinity? The surprising answer was, kind of, yes. When the price goes to zero, the demand increases significantly. The way this e-commerce tested it was by having products that they had acquired accidentally, and the general consensus about those products was that they were unsellable due to their awful taste, bad colors, and poor quality. There were no redeeming qualities for those products, and they believed there was literally no demand for them in the market. However, they wanted to test this hypothesis and decided to put the products on display on their website with a retail price of zero. Clients still had to pay shipping fees, but the product itself was free. Surprisingly, nearly everything was liquidated, which showed that demand could reach extremely large quantities when the price was significantly reduced.

It’s not so surprising when you think about fashion. Even a company doing one billion a year isn’t capturing even one percent of the general fashion market. If you can have a price that is vastly better than the rest of the competition, the demand you observe can be one or two orders of magnitude greater than what you usually experience. Pricing, from my perspective, is very much a supply chain problem. Deciding to have a higher or lower price will have a profound influence on the amount of demand you observe. Supply chains need to leverage all these options to maximize the value they generate through the company and the brand.

Now that we’ve established our assortment, we need to decide how to produce it. In this example, I’m assuming the company is completely outsourcing its production, relying on third-party suppliers predominantly located in Asia. This choice is motivated by the fact that it’s a common practice for fashion companies in Europe and North America.

We have to start thinking about lead times. The total lead time of interest, from the generation of purchase orders passed to a supplier to the reception of the goods, will be something like four to six months. However, if we look at only the transportation time, it takes about 30 to 35 days to ship containers via sea from China or Vietnam to Europe. Transportation time is a notable fraction of the lead time, but it’s not the biggest part.

The bulk of the four to six months lead time is required for the supplier to acquire their own raw materials and produce the merchandise. At this point in the journey, we have an assortment, and we have to decide what quantities to buy. The first thing we must consider is constraints. We typically need to be compliant with MOQs (Minimum Order Quantities), but there are many flavors of MOQs, and usually, most of them can be found. For example, we can have an MOQ at the product level, at the variant level, which is down to the final reference with the variations in terms of size and colors. We can have MOQs that apply at the purchase order level, where, for example, suppliers say you cannot pass a purchase order if, in total aggregate, it’s not at least 50,000 pieces. It can also be more sophisticated MOQs, such as the supplier saying you can pick any color you want, but for every color you pick, you need to have an MOQ expressed as 3,000 meters of fabric of that color. MOQs are not just one problem; it’s a whole spectrum of constraints.

Additionally, we have price breaks, where there are economies of scale, and the supplier will offer a decreasing per-unit price as the quantity increases. The optimization of the purchase order isn’t just about having one variant and one quantity; there are plenty of things that need to be accommodated and plenty of forces at play. Ultimately, we want all of that to reflect the capacity of the network to sell the merchandise, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

Once the purchase order is passed, the problem doesn’t stop there. Now we have to think about shipping angles. For example, a company might have several suppliers nearby in Vietnam, and there might be an interest in consolidating the production of those suppliers into containers. Instead of having every single supplier send full containers, we can think about consolidating the production of multiple suppliers into containers prior to shipment.

We also have to think in terms of transportation modes. Typically, a mid-market fashion brand like the one in our example has to convey the bulk of the merchandise through sea for economical reasons. However, it is possible for certain articles of higher value to be transported by air. The cost that dominates air transportation is weight, whereas for sea transportation, it’s volume. When planning a shipment, it sometimes makes sense to have a mix, with a full container arriving by sea in about 30-35 days, and a fraction sent by air to arrive earlier. There may be plenty of reasons to choose a mix of transportation modes, such as solving an early stockout that the company is already facing or starting to test the waters early. This could involve selling the product and putting it on display in e-commerce to gauge demand or doing a test run in the stores themselves, or even conducting quality assurance assessments. There is a variety of reasons why choosing a mix of transportation modes can be beneficial.

The total lead time is typically four to six months, which means that the company needs to be very careful in its planning. Most of the products being purchased have a seasonality of their own. For example, it’s pointless to have a winter coat arrive in March; you want the winter coat to arrive at the distribution center in September, so it can be in the store by October. In terms of scheduling, the producer should consider whether to produce and ship everything at once or, if the quantity allows, start producing and shipping containers gradually, depending on what is being produced and consumed within the actual network.

Another consideration is the use of master packs. A master pack is a simple idea where a box contains a mini assortment of products. Typically, a box might contain many units of the same variant, such as 200 t-shirts. The question is whether to have one box that contains a mini assortment. This is interesting because it can save on handling costs, as the box can be sent to the distribution center without being opened and then directly sent to the store. However, the downside is that we lose a great deal of flexibility with master packs, as they create a more rigid bundle of products that must be sent to stores at once.

Now that things have been purchased and are on their way, they will eventually arrive at the inbound distribution center. The first decision that will have to be made regarding the distribution center is determining the destination for the containers. We can decide to send containers to a distribution center in Germany, alternate between the two distribution centers, or send a container to one distribution center and then redistribute the excess quantity to the second distribution center. In Europe, the two distribution centers are about a day’s road distance apart, so they are not very far.

Then there is the question of cross-docking. If you have an incoming container that contains boxes intended for both the French and German distribution centers, you really want to do a cross-dock operation. What you don’t want to do is have the container arrive in your distribution center, unload all the boxes, put them in storage, and then pick them back to ship them to Germany. What you want is, as you unload, to directly cross-dock all the boxes so that you can immediately resend them and avoid many manual operations that would involve putting the box in storage and then taking it back. This would be the first operation, and you have to do that for every single incoming container because even if initially you thought that this container was only intended for this distribution center, the market situation may have evolved, and there is an opportunity to do a bit of a cross-dock operation to do an immediate rebalancing of the merchandise as it arrives.

Then you have to decide what you unpack. For quality control, you want to unpack some items. However, as soon as you start unpacking the goods, it will take up more space, so that needs to be taken into account. If you don’t do that, the productivity can be relatively low when it comes to picking, for example, for the e-commerce that you have to serve. Typically, e-commerce shipments are done from one of the two distribution centers in this scenario. Obviously, we have to take into account the constraints, such as the storage capacity of the distribution center, so that if we send many more containers at a specific period of time due to the collection, we have to make sure that the distribution center is not going to be overwhelmed capacity-wise by all the arrivals from Asia at a specific point in time during the year.

Now that we have the merchandise in the distribution center, we have to decide what we are going to push. There is typically an initial push for the collection; it’s just a matter of consistency. A new collection comes with a new theme, a bit of storytelling, and maybe some marketing operations, and we need some consistency. Thus, there is typically an initial push to be done to the stores. Here, the idea is that we have many drivers at play. The first idea is to boost the appeal of the store.

For example, an anecdote from another client a decade ago: we had a discussion because I was a bit surprised. It turned out that in every single store, they were pushing one unit of a white leather bag. It was a bit surprising to me because, when I was looking at the sales volume, brown or black leather bags vastly dominated in terms of sales volume. White leather bags, which are perceived as very fragile, had very low sales volumes. The question for me was a bit puzzling: why push one unit of the white leather bag in every single store, although the volumes are very low? The answer given to me, which still resonates strongly, is that because if all the leather bags you have are basically brown or black, the store looks a bit sad; it needs a touch of vibrant color to be very appealing. That means you have to decide to put some products not because they are going to be sold, but just because in terms of merchandising and visual effect, they really boost the attractiveness of the store. One of the concerns we have here is that we want to maximize the appeal so that clientele is enticed to enter the store.

What we want is to make sure that once the client walks into the store, there is a high quality of service. However, based on our understanding of this scenario, when we come to quality of service, are we really talking about service level? I would say not at all. A woman that enters a store very rarely has a specific product reference in mind. She might have some plans, some general interest, and some general preferences, but the idea that this person has a specific product in mind might be possible, but it’s just very marginal. In the store, if a product happens to be out of stock but there are plenty of valid substitutes, then the problem of the stockout is kind of irrelevant. Even worse, if the person walks into the store and the product she’s looking for is not there because the product never made its way into the assortment in the first place, you will never even see that you have a quality of service problem. We have to really think in terms of quality of service, but as we have just briefly demonstrated, this quality of service has almost nothing to do with service levels.

So, we want to have good appeal, good quality of service, and then there are all the financial drivers. Some products have a margin; there is profit to be made by selling those products. Then there are all the costs involved: carrying costs, working capital costs, and so on. These constitute all the drivers that we have to deal with. We also have a whole series of constraints that apply to this initial push. First, we have the store capacity. As I was describing, we have power stores that sell a lot, but they have a very limited amount of floor surface. It’s a bit of a paradox: the stores where we would like to push the most inventory are also the stores where we technically can’t. Conversely, at the other end of the spectrum, we have some weak stores with a lot of square meters, but it would not be reasonable to push tons of stock just because the store is not really selling very well and will not be able to liquidate all this inventory.

Then, obviously, we have the plan for what we want to push, but we have to accommodate what is already in the store. For example, if the previous collection went exceedingly well and the store is nearly empty, you might want to push even more merchandise because otherwise, it’s not going to be appealing enough. Conversely, if the previous collection went a bit badly and you have tons of leftover, you might not even have enough room physically in the stores to accommodate all the incoming merchandise. When it comes to store capacity, we have to keep in mind that it’s not only dependent on the size of the store but also the size of the articles. For example, obviously, you can store many more t-shirts in a store compared to winter coats, as one is much more bulky than the other. The capacity in the store also depends on the sort of hardware equipment you have to put the goods on display. This goes both ways: you can have equipment that gives the impression of plentiness, which is of high interest for weak stores, and some stores can have a more compact setup for power stores that are limited in space.

Then, we have the routine push, also called store replenishment or the dispatch from the distribution centers. Between the store routine push and the store initial push, there are no well-defined boundaries; it’s more like a spectrum. At the beginning of any collection, you need to push things, but then you need to replenish. It’s a continuum rather than two radically different things. Nonetheless, as we start thinking about store replenishment, we have to consider the delivery schedules. In this scenario, we have one distribution center serving several hundred stores. The question is, is it really of interest to serve every single store every single day? There are transportation costs to pay for the fleet of drivers, but every single day where you’re actually making a delivery to a store, you most likely have some extra cost as well.

The reason being is that, for example, in Europe, due to traffic reasons, deliveries usually have to be made early during the day. The delivery will be made one or two hours before the opening hours of the stores, which means that if you intend to deliver a store on a given day, an employee will have to be present and be paid for one or two extra hours. If the same driver delivers to 15 stores, you have to basically add 10 hours of extra employee pay to the cost, which can add a lot in terms of delivery costs. These schedules can be established completely dynamically; these are all the supply chain options that are on the table on any single day.

Then, we have constraints both at the distribution center and at the store level. Let’s consider any unit in stock, and we have to think that all the stores compete for the same units of stock that are currently held in the distribution center. To give you an idea, let’s say we have a weak store that, during the initial push, had one unit for one variant. After 10 weeks, this one unit has just been sold, so technically, this weak store is out of stock for this one variant. In the distribution center, we have, let’s say, 10 units left of this variant. Should we immediately send another unit to this weak store to solve this stockout problem? It’s not quite clear because let’s imagine that at the same time, we have a power store that has three units in stock. The power store is not out of stock and cannot even accommodate more stock at the moment. There are three units in stock, and that’s the max they can accommodate, considering the rest of what they have in storage. Now, the problem is that this power store might be selling one unit per day for the same product. If we push one of those remaining units from the distribution center to the weak store, it’s very likely that this unit will take 10 weeks to be sold. Worse, this unit might actually be sold at a discount because we are going to end up in the end-of-season sales period. However, if we preserve this unit in stock for later replenishment for the power store, we have a great chance of selling this unit within two weeks at a high price. You see, all the stores compete, and that means that it’s not always profitable to solve stockout problems as the stores are competing for the same stock.

We also need to think about input and output problems from the distribution center perspective. What is most efficient is to have a very flat level of activity. If we have a varying level of activity, we either have to pay the regular employees overtime to cope with a spike, and if the spike is too large, we have to bring in temporary workforces. Temporary workforces are not naturally more expensive per hour, although they can be more expensive than the regular workforce. However, they are usually not as competent or experienced, and thus the productivity is lower. In terms of actual cost, it can be much more costly due to the reduced productivity of the temporary workforce. From the distribution center’s perspective, it is of interest to have a completely flat level of activity.

From the perspective of the stores, it’s also of interest to have a relatively flat level of reception. If we send 20 boxes on a given day, the staff might not have the capacity and the manpower it takes to put all those products on display at the beginning of the day. This could result in a fairly messy store, possibly for several days. It is of great interest for the stores to receive the incoming products somewhat incrementally. The drivers for replenishment are very much the same: we want to preserve the appeal of the stores, maintain a high quality of service, and maximize the financial drivers, which is maximum profitability while minimizing the cost. The drivers are fundamentally exactly the same.

As a tangential note, we also have reverse logistics, which is in opposition to forward logistics. Let’s imagine a situation where the distribution center has run out of stock for a given variant, but on the e-commerce platform, this product is still selling very well. There might be some weak stores that have some units left in stock, and they are slow movers. Maybe it is of interest to bring the stock back to the distribution center so that it can be sold via e-commerce, for example. Obviously, it costs money, but it’s probably better to sell the product at full price via e-commerce than to wait until the end of the collection and give a 50% discount on the product so that it’s finally liquidated. We can also have a lot of inter-store inventory rebalancing, especially if a couple of stores happen to be physically very close by. For example, in a large city like Paris or Berlin, it’s very likely that there are about five stores just one or two kilometers apart. It can be of great interest to do some minimal rebalancing between those stores, maybe not even going through the distribution center’s delivery route. If something is out of stock in a store and there is a little bit of excess for the same product in another store that is nearby, it’s better to spread the inventory around.

We have already previously discussed pre-season pricing, but pricing, in general, remains very much an option on the table at any point in time. We can do a lot of demand shaping. For example, we can do promotions at any point in time. By promotion, I mean the word in its literal sense: to promote or put forward. You can promote a product by making it more visible or prominent in the store. If we see that we have a problem with a product where we are at risk of having some kind of overstock, it might be a good time to promote the product. There is also the option of doing some bundling, for example, “buy two, get the third one for free” or more complex offerings. We can even do flash sales, especially if there is a loyalty program in place where you can make direct targeted offers to clients.

From my perspective, this is also very much a supply chain problem because it’s about the fact that you initially had a four to six months lead time, which is very large. Fashion is very erratic, so you need to accommodate this erraticity. You can try to accurately predict future demand, but it’s going to be fuzzy at best. Whatever you can do to mitigate the areas where you guess wrong, it can be a very powerful supply chain mechanism.

Obviously, you have the practice of doing end-of-season sales, where the idea is to maximize the volume of sales from the fixed amount of inventory that you have. You hope to have more or less liquidated it by the end of the season to make room for the next collection in your stores. Here, we have to consider customer habits and perceptions, which are a double-edged sword. On the plus side, whenever our clients show up and buy something from the brand, it creates loyalty towards the brand. The more you buy from one brand, the less you buy from competing brands, so that’s very good. However, the problem is that whenever you give a discount, especially at the end of the season, you create a habit of buying at a discounted price. The client who has just bought a product at a 50% discount might, for the next season, start waiting until the end of the collection to benefit from the discount again. If we go more upmarket than this brand, for example, in soft luxury, the brands would typically never do any discounts precisely because of this problem. Here, we have a mid-market brand, and they have to resort to this mechanism. It’s quite profitable to do so, but we have to take into account both aspects of the problem. It’s a matter of supply chain trade-off optimization to leverage this to our best interest.

As a transitional note, in the past, there were limitations on how frequently you could change the price point of your products. In e-commerce, you can change the price of a product on any single day. However, in a physical store, there is typically manpower involved if you want to re-tag all your products. More recently, electronic price labels have emerged that let you re-price your products as frequently as you’d like. Even if it’s not overly frequent at present, if we look one decade from now, these options will be even more prevalent because the brand will not have to pay people to re-tag products whenever they want to change the price.

We are already past one hour, and there are plenty of other elements to cover, so I won’t have time in this lecture to address everything. In particular, I’ve barely touched on the e-commerce angle. Fashion e-commerce deserves a discussion of its own. Let’s briefly mention some of the problems we haven’t touched yet, such as returns. For example, in Germany, for fashion e-commerce, we can easily expect 50% returns, so one article out of two purchased online ends up returned to the brand. In France, the percentage is much lower, at about 10%, due to cultural differences. This has a profound influence on how you organize your e-commerce operations and optimize them.

If you’re doing e-commerce, you can do “naked sales” in the sense that you don’t need to have the product in stock physically to sell it. If the product is incoming in a container, you can already start selling it, provided that you’re transparent about the estimated time of arrival for your client. You don’t want to over-promise a delivery two days from now if it’s going to take four weeks to arrive. Nonetheless, you can start selling the product even before the stock is there.

Then, there is the showrooming effect where clients see products in a store, and they really like the product and the fit, but they would prefer a different color. They may decide in-store but actually purchase online. Conversely, there is the opposite scenario where a customer purchases online and receives the delivery in the store just so they can immediately return the product if it doesn’t fit and ensure they get the exact product they seek.

There are also other channels that are excluded from this discussion, such as online marketplaces where the brand could sell its products, or wholesale, where the brand sells its products to other B2B clients that have their own separate retail chains. There might also be third-party outlets that are co-managed to some extent between the brand and a third-party company. Another aspect that has been brushed aside for now is the intricacies related to franchises. Typically, fashion retail networks have both a portion of the network that they directly own and a portion that is operated independently by franchisees. Depending on the setup, there might be more or less leeway for the franchisees to make their own stocking and pricing decisions. However, addressing these aspects would open up plenty of other questions that we will just brush aside for now.

In conclusion, today we have covered quite a list of supply chain decisions. We have discussed decisions related to range planning, purchasing, finding the right shipment methods, handling reception in the distribution center, the initial push and subsequent replenishment, and pricing-related problems. We can see that all these supply chain decisions are completely entangled. For example, an initial range planning decision will have a profound impact on purchasing, which in turn affects the initial push and replenishment, the quality of service, overstocks, and the discounts given at the end of the season.

This entanglement is the essence of one of the principles introduced in the lecture about the quantitative principles of supply chain. If we try to solve these problems locally, we just displace the problems, we don’t address them. In conclusion, based on our understanding of this case study, we should be exceedingly skeptical of the divide-and-conquer approach, as it is nearly guaranteed to miss the point due to this entanglement. We should be very skeptical about the sort of functional decomposition of the process. For example, if we say that we have a forecast plan and then optimize the sequential functional decomposition of the process, it completely violates what we understand about the problem itself and the entanglement that we have observed for all these decisions.

This completes our discussion on the first supply chain case study, and two weeks from now, at the same day of the week and time of the day, I will be giving the next lecture about experimental optimization. This is our journey to find scientific methods for supply chain or, at least, something that can provide more solid foundations when it comes to the predictable and controlled improvement of supply chains.

Now, I will start looking at the questions.

Question: Micro fulfillment centers are needed in Asia’s dense cities where space is limited and order turnaround time is very low (delivery in 3 hours). Enterprises lose efficiencies in multi-story distribution center layouts. How to deal with warehouse operations efficiency for multi-story, multi-level micro distribution centers with activity operation and getting customized warehouse management software based on process and layout?

That’s a very interesting angle that was not covered in this case study, as I was focusing on a European setup. What you’re describing highlights the importance of understanding the problem. If we have, for example, a multi-level micro-distribution center, we have many extra options that emerge. Where should we put the products when we receive them, on which floor? The topology of the building starts to matter a great deal more, especially if it’s a building that was not initially designed as a distribution center.

Today, I’m not going to delve into the actual solutions, but I would say, if we want to stick to this idea of supply chain case studies, first, we need to characterize the forces that are at play and the problems we face. For example, if it’s a very small facility, we may be limited in the number of people we can actually put in the building. At some point, there are diminishing returns if we add more manpower to a micro-distribution center, as there may not be enough room for people to circulate. In that case, maybe we should start thinking about organizing the storage differently, helping people find items more easily, or reevaluating the exact internal layout. Another possibility could be having a night shift dedicated to reorganizing the stock within the micro-distribution center so that the day team can be more productive. The main goal of this lecture is not to discuss the exact solutions, but to expand our understanding of the problem. Stay tuned for later lectures where we may dive deeper into potential solutions.

Question: What do you think about existing solutions in multi-echelon inventory optimization, especially coupled with demand sensing?

I produced a Lokad TV episode on demand sensing, and I can definitively say that it is essentially nonsense and marketing buzzword with no substance. If you see the keywords “demand sensing,” you can be assured that the vendor has little understanding of the subject. If you want proof of that, I suggest watching the demand sensing episode we produced a few months ago on Lokad TV.

As for existing solutions in multi-echelon inventory optimization, we need to start by examining the definition of the problem and its characteristics. Most of the decisions in multi-echelon optimization do not need to be made in real-time. For the case study discussed today, almost zero decisions needed to be made in real-time. Most existing multi-echelon inventory solutions are software-wise designed around relational databases that are geared for real-time transactionality. However, real-time transactionality is not required for most decisions made in supply chain optimization.

In this case study, we are not really discussing a multi-echelon supply chain, but rather a two-echelon supply chain. Do we need real-time decision-making for most of the decisions we’re talking about? Absolutely not. We need transactionality whenever we’re selling a product or moving inventory within the distribution center, but that is not what supply chain optimization is about. So, when looking at existing multi-echelon inventory optimization software, my question to you would be: start looking at the problem, just like what we did today with the persona, and assess whether the core fundamental design decisions that went into the software are aligned with the problem or whether they’re completely at odds. In my opinion, the vast majority of the software products you will find in the market for multi-echelon inventory optimization have designs that completely antagonize the very problem they’re trying to solve. You can detect this by a simple litmus test: ask the vendor if they use an SQL database. If the answer is yes, you know that the software is misdesigned with regard to the problem, and you can rule out that vendor and move on to the next one.

Question: When we craft a persona, even though it might look very realistic, it is a thought experiment endeavor; therefore, we operate in a hypothetical situation. How can we generate datasets to study its dynamics?

Generating synthetic datasets that are realistic is exceedingly difficult. At Lokad, we’ve tried, especially because we have some sample datasets lying around, and it took us a lot of effort to create those. The easiest way to create a sample dataset is to use real data and anonymize it.

This question is very relevant, and it touches on the point I discussed in the previous lecture. The way I have engineered this persona is such that, while it sounds realistic, it is also easily contradicted. For example, a fashion brand might say that they have 500 stores but 100 distribution centers, or that they only have 50 variants instead of 10,000. A supply chain director could object and say that the problem I presented is non-existent for their fashion brand, as they import from China and the deliveries are made directly to the stores with no distribution centers.

The persona methodology I introduced a few weeks ago cannot be proven correct, but it is maximally exposed so that it can be easily contradicted. This is a qualitative approach, and unfortunately, that’s the limit of this perspective. It can be enriched potentially with a synthetic data set, but that’s a very difficult undertaking. This would make the approach more prone to quantitative studies. However, don’t despair, as today I took a very qualitative perspective. Two weeks from now, we will be discussing a methodology to gain quantitative insight and knowledge about the supply chain. That’s exactly what experimental optimization is about.

Question: Wouldn’t using stores with lower sales, such as suburban stores, as pseudo distribution centers (DCs) help Paris improve their stock optimization further at the distribution level? What are your thoughts?

Well, the problem is both yes and no. The issue is that those stores are completely lacking all the equipment that distribution centers have. Distribution centers are literally big, complex machines. They have conveyor belts, packaging machines, and tons of other equipment that they can use to organize shipments.

The problem with those smaller stores is that, first, they are typically in the middle of nowhere, so they’re not necessarily very close to, for example, a highway. This makes it not the most practical place to use as a hub. Additionally, there might be nothing really prepared in the store for distribution purposes. In terms of square meters, it’s cheaper than a large store, but it’s nowhere as cheap as a distribution center, which is typically located next to a highway, literally in the middle of absolutely nowhere. The price per square meter in distribution centers is super low.

Those smaller stores have a lower price per square meter than large stores, but we are still talking about an area with modest commercial attractivity. The price point per square meter is still sizable. If all you want to do is carry out industrial operations, you would prefer to do that in a place where the square meter is worth next to nothing.

That concludes all the questions I have for today. Thank you very much to the audience, and it will be a pleasure to see you two weeks from now for the next lecture. Goodbye!